My friend, mentor, patron and lab Godfather, Ken Murray, died on Saturday, aged 95.

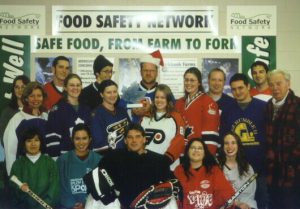

I’m going to inter-splice some personal notes with the official obituary, and this may not be the best writing because I am flooded with memories, but here it is (that’s Ken’s head in the middle of my 2005 lab, where we had gathered at their place, and I slept there because stalker girlfriend was on the loose).

I’m going to inter-splice some personal notes with the official obituary, and this may not be the best writing because I am flooded with memories, but here it is (that’s Ken’s head in the middle of my 2005 lab, where we had gathered at their place, and I slept there because stalker girlfriend was on the loose).

After a long full life, lived with purpose and generosity, Ken Murray died peacefully in Guelph at Hospice Wellington in his 95th year on Saturday March 2, 2019. He is survived by his wife Marilyn, his daughters Susan Pearce (Richard) and Leslie Harwood (Fred), his grandchildren Andrew Harwood (Kristin) and Lauren Harwood, and his great grandson James Murray Harwood.

He was only at the hospice for a couple of days.

He is lovingly remembered by Marilyn’s children and the extended Robinson family. Ken was predeceased by his first wife Helen Volker (1995), his brother Donald (Margaret), sister Jean Shetler (Elmer) and parents George Murray and Vera Irwin.

A son of the manse, Ken was born in 1924 in Chatham Ontario and grew up in small town Ontario – Buxton, Newbury, Zephyr and Keene. After serving two years in the Canadian Navy during the Second World War he enrolled in the Ontario Agricultural College in 1946, married Helen Volker from Kitchener in 1948 and graduated in 1950 with a BSc (Agriculture). His first job was as a salesman for J.M Schneider Inc. in Kitchener, and he retired in 1987 as president.

Wait, that’s modest. The dude was president of J.M. Schneider Inc. in Kitchener, Ontario (that’s in Canada) and both Ken and the company were pillars of the community, and Canada.

My ex and I lived on Queen St. in Kitchener, not far from Schneider’s, for seven years, and just down the road from the Schneider historical house (and there he is, far right, in this 2002 lab photo).

My ex and I lived on Queen St. in Kitchener, not far from Schneider’s, for seven years, and just down the road from the Schneider historical house (and there he is, far right, in this 2002 lab photo).

Schneider (which was swallowed by Maple Leaf in 2003) and Seagram in neighbouring Waterloo (which is now a museum) were essential for the surrounding agricultural areas in the mid-20th century to convert their commodities into products people wanted: booze and meat.

I first met Ken and Marilyn in 1995.

Someone at the University of Guelph said Ken Murray would like to meet with you.

In 1995, I was a cocky PhD student and about to be a father for the fourth time.

I rode my bike to a local golf club, met the former long-time president of Schneiders Meats, and established a lifelong friendship.

Fairly fancy surroundings, reminding me of my caddy days at the Brantford Golf and Country Club, where the caddies weren’t allowed in the Club but were allowed out on the course for a round before 8 a.m. on Mondays (I lived the movie, Caddyshack).

Within moments, Ken and I were talking about our families who had suffered from Alzheimer’s – his wife, my grandfather – the effect on others and how accommodation could be bettered.

It was a special moment, that had nothing to do with surroundings and everything to do with compassion and curiosity.

Ken had heard I might know something of science-and-society stuff.

Ken shared his frustration that food irradiation had not been approved for meats in Canada, and was curious about my interests in the intersections between science and society (by that time I had been teaching engineering students at the University of Waterloo in science, technology and values for five years; keeping 100 engineering students engaged in a 3-hour night class they didn’t want to take was a fabulous learning experience, for me).

Ken funded my faculty position at the University of Guelph for the first two years.

Sure, other weasels at Guelph tried to appropriate the money, but Ken would have none of it.

For over 20 years now, I’ve tried to promote Ken’s vision, of making the best technology available to enhance the safety of the food supply.

Following retirement, Ken played a leadership role for more than 20 years at the Homewood Health Centre, serving as President and Chair, creating the Homewood Foundation and sitting on the Homewood Research Institute Board (that’s me and Ken and Marilyn when I was awarded aggie extension-type of the year in 2003)

Following retirement, Ken played a leadership role for more than 20 years at the Homewood Health Centre, serving as President and Chair, creating the Homewood Foundation and sitting on the Homewood Research Institute Board (that’s me and Ken and Marilyn when I was awarded aggie extension-type of the year in 2003)

Raising beef cattle was a favorite pastime for Ken, both on his home farm in North Dumfries Township and later in Bruce County.

Ken lived his life following the example of his minister father. He loved and was proud of his family. He was committed to the communities where he lived. He believed in giving back. He revelled in meeting new people. He found joy in supporting local causes and participating in their activities and special events.

He was an active church member in the communities where he lived: Trinity United, Kitchener; Knox United, Ayr; Ellis Pioneer Chapel, Puslinch Twp and Harcourt Memorial United, Guelph.

Many organizations in Kitchener-Waterloo, Guelph and beyond benefitted from his leadership and support. The Universities of Guelph, Waterloo and Laurier have all benefitted from Ken’s generous spirit, particularly his support for student scholarships and awards and he has received numerous honors and awards in recognition of those contributions.

He received honorary degrees from the University of Waterloo (1995) and the University of Guelph (1996). And one of his proudest moments was in 2001 when he became a member of the Order of Canada.

In 1996, Ken married Marilyn Robinson, who has been his soulmate and loving partner for more than 22 years. Together they continued their love of volunteering, travelling and connecting with family and friends.

When my ex and I moved into our newly-built house in Guelph in 1997, Marilyn showed up to our open house and I said, where’s Ken?

He’s on his way.

About 30 minutes later Ken showed up, driving his lawn mower with a load of firewood on the trailer.

When Lester Crawford, former head of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, camped with us for a couple of days in Guelph, Ken was there, asking questions.

When the Listeria outbreak hit Maple Leaf in 2008, in which 23 died, I asked Ken, any ideas?

Ken reminded me how he used to walk the Schneider’s plant every morning, talk to every employee, just like the best university presidents do instead of being locked away in some ivory tower, and he said, I always worried about those slicers.

The deadly Listeria was found hidden deep in those industrial slicers at other Maple Leaf plants.

But Ken (and Marilyn) seemed most delighted hanging out with the various characters in my lab (older version, left).

But Ken (and Marilyn) seemed most delighted hanging out with the various characters in my lab (older version, left).

Ken had a curiosity and a genuine interest in the human condition, whatever one’s status, that is foundational and resonates with me.

A colleague said that Ken viewed me as a son.

I read that, I cried, and thought I could never be worthy enough.

That colleague wrote back, “Doug, being a son has nothing to do with worthiness, but, rather, love. However, you did him proud and never doubt that. If we start looking for faults, we all have long lists.”

I was so proud to know him,

And to continue to share with Marilyn.

A celebration of Ken’s life will take place at Harcourt Memorial United Church, 87 Dean Ave., Guelph on Saturday, March 30 at 1 pm. Burial will take place at a later date at the Ayr Cemetery, Ayr Ontario.

In lieu of flowers and in memory of Ken, please consider a donation to the Ken Murray Fund at the Kitchener Waterloo Community Foundation, Harcourt Memorial United Church, Guelph or Hospice Wellington. Cards are available at Gilbert MacIntyre & Son Funeral Home, 1099 Gordon St., Guelph (519) 821-5077, or donations and condolences may be made at www.gilbertmacintyreandson.com

Ken and I are landlubbers, not sailors, but this song resonates.