For former Kansas State University professor of food safety Doug Powell, E. coli isn’t an illness that only appears on his radar during an outbreak like the one traced to Chipotle this fall by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Powell, who in 2013 moved with his wife to Brisbane, Australia (actually it was 2011; it was 2013 when Kansas State decided to dump me for bad attendance), compiles stories of foodborne illness daily on his blog, barfblog.com. Writing about it is his life’s career, he said by phone Friday, from Brisbane, to Samantha Foster of the Topeka Capital-Journal (that’s in Kansas, irony can be pretty ironic sometimes).

Powell, who in 2013 moved with his wife to Brisbane, Australia (actually it was 2011; it was 2013 when Kansas State decided to dump me for bad attendance), compiles stories of foodborne illness daily on his blog, barfblog.com. Writing about it is his life’s career, he said by phone Friday, from Brisbane, to Samantha Foster of the Topeka Capital-Journal (that’s in Kansas, irony can be pretty ironic sometimes).

“Forty-eight million people get sick from the food and water they consume in the U.S. every year,” Powell said. “If we can make a little bit of a dent in that, then that’s a good reason to get out of bed in the morning.

When Powell started the blog — before Google and other developments made such information more readily available, he said — its purpose was to provide information so people could make informed choices. He said he doesn’t try to preach what to do or not do.

“When I started this 20 years ago, it was largely about parents saying, ‘We never knew,’ ” he said. “I wanted to make sure there was never a case where they said that.”

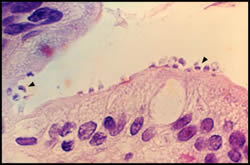

In a blog post Friday, Powell wrote about a Jefferson County family whose child became infected with a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli — the most virulent type of E. coli. The 8-year-old Meriden boy’s symptoms progressed from severe diarrhea to a point at which his kidneys began to shut down, Powell wrote.

According to the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, 106 cases of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli had been reported across the state this year as of Tuesday. Of those, 11 were reported in Shawnee County. Compared with 2014’s statistics, this year’s are slightly higher, with 90 cases reported statewide, four of which occurred in Shawnee County.

According to the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, 106 cases of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli had been reported across the state this year as of Tuesday. Of those, 11 were reported in Shawnee County. Compared with 2014’s statistics, this year’s are slightly higher, with 90 cases reported statewide, four of which occurred in Shawnee County.

“We don’t know definitively why there are more reported cases this year compared to most previous years,” said KDHE spokeswoman Cassie Sparks. “It could be the actual incidence is slightly higher. It could also be with the increased attention in the news lately, that physicians are testing more frequently, so more cases that are occurring are being identified.

“Infectious diseases also tend to cycle. In 2011, we had 108 cases reported for the year, so that was a little higher than usual as well.”

Powell said some research has shown physicians are more likely to check for a specific disease if it has been in the news. If they were to check for everything, that would be expensive and time-consuming, he said.

“When there’s something in the news, it triggers doctors to look harder for it,” he said.

Though Powell said the source of the Meriden boy’s E. coli isn’t clear and doesn’t seem to be part of an outbreak, isolated incidents are frequent and often tragic, sometimes causing lasting problems, he said.

KDHE’s annual reports, available online, state that E. coli occurs when susceptible individuals ingest food or liquids contaminated with human or animal feces. Outbreaks have been linked to eating undercooked ground beef, consuming contaminated produce and drinking contaminated water or unpasteurized juice. Person-to-person contact, especially within daycares or nursing homes, also can spread the disease, according to the reports.

Powell said he personally won’t eat many raw foods, including sprouts, oysters and unpasteurized milk. Produce, however, is problematic. Fresh fruits and vegetables are the cornerstone of a healthy diet, he said, though at the same time, they are the leading cause of foodborne illness in the U.S.

Powell said he personally won’t eat many raw foods, including sprouts, oysters and unpasteurized milk. Produce, however, is problematic. Fresh fruits and vegetables are the cornerstone of a healthy diet, he said, though at the same time, they are the leading cause of foodborne illness in the U.S.

Farm food safety programs are critical to keeping the poop out of the produce, Powell said.

“That entails paying attention to what you’re adding to your soil, whether it’s raw manure or other things,” he said. “It means knowing your source of irrigation water, because often … there’s been a flood situation and it’s coming from a cattle farm loaded with E. coli, and that becomes the water for the produce.”

Good hand-washing also is critical for farm employees, Powell said, because once produce is contaminated, soap and water do little to stop the bacteria.

“It has to be prevented on the farm, as much as possible,” Powell said.

Five people in Kansas have become ill as part of this outbreak after consuming sprouts from Sweetwater Farms, Inman, KS. The last date of illness was January 21 in a Kansas resident. In addition, three residents from Oklahoma also have Salmonella infections that match the outbreak strain.

Five people in Kansas have become ill as part of this outbreak after consuming sprouts from Sweetwater Farms, Inman, KS. The last date of illness was January 21 in a Kansas resident. In addition, three residents from Oklahoma also have Salmonella infections that match the outbreak strain.