To properly assess a food establishment for compliance with local food safety regulations is a science and an art. They take time and energy.

The science is applying risk assessment to determine the severity of the public health violation and the art is being able to effectively communicate the findings to the operator or Person-in-Charge. On-site training of the cited violations is an additional effort conducted by inspectors time permitting.

A recent study “How Scheduling Can Bias Quality Assessment: Evidence from Food Safety Inspections,” co-written by Maria Ibáñez and Mike Toffel, looks at how scheduling affects workers’ behavior and how that affects quality or productivity. In the study the authors suggest reducing the amount of given inspections during the day as fatigue will negatively affect the quality of successive inspections . As such a cap on inspections should be implemented to correct this issue. As much as I agree with this statement, the problem stems from inadequate resources to hire more staff to conduct inspections. Many inspectors are generalists meaning that on any given day they may be required to inspect a restaurant, on-site sewage system, playground, pool and deal with any environmental health issues that arise. Unfortunately, quality is sometimes sacrificed by quantity simply due to a lack of staff.

Carmen Nobel reports:

Simple tweaks to the schedules of food safety inspectors could result in hundreds of thousands of currently overlooked violations being discovered and cited across the United States every year, according to new research about how scheduling affects worker behavior.

The potential result: Americans could avoid 19 million foodborne illnesses, nearly 51,000 hospitalizations, and billions of dollars of related medical costs.

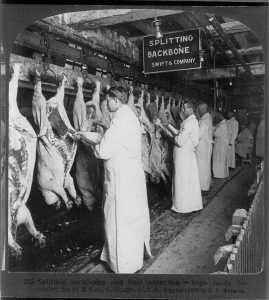

Government health officers routinely drop in to inspect restaurants, grocery stores, schools, and other food-handling establishments, checking whether they adhere to public health regulations. The rules are strict. Food businesses where serious violations are found must clean up their acts quickly or risk being shut down.

Yet each year some 48 million Americans get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die due to foodborne illnesses, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

The research is detailed in the paper “How Scheduling Can Bias Quality Assessment: Evidence from Food Safety Inspections,” co-written by Maria Ibáñez, a doctoral student in the Technology and Operations Management Unit at Harvard Business School, and Mike Toffel, the Senator John Heinz Professor of Environmental Management at HBS, experts in scheduling and in inspections, respectively.

“The more inspections you have done earlier in the day, the more tired you’re going to be and the less energy you’re going to have to discover violations”

“This study brought together Maria’s interest in how scheduling affects workers’ behavior and how that affects quality or productivity, and my interest in studying the effectiveness of inspections of global supply chainsand of factories in the US,” Toffel says.

Timing is everything

Previous research (pdf) showed that the accuracy of third-party audits is affected by factors such as the inspector’s gender and work experience. Ibáñez and Toffel wanted to look at the effect of scheduling because it’s relatively easy for organizations to fix those problems.

The researchers studied a sampling of data from Hazel Analytics, which gathers food safety inspections from local governments across the United States. The sample included information on 12,017 inspections by 86 inspectors over several years; the inspected establishments included 3,399 restaurants, grocers, and schools in Alaska, Illinois, and New Jersey. The information contained names of the inspectors and establishments inspected, date and time of the inspection, and violations recorded.

In addition to studying quantitative data, Ibáñez spent several weeks accompanying food safety inspectors on their daily rounds. This allowed her to see firsthand how seriously inspectors took their jobs, how they made decisions, and the challenges they faced in the course of their workdays. “I’m impressed with inspectors,” she says. “They are the most dedicated people in the world.”

Undetected violations

Analyzing the food safety inspection records, the researchers found significant inconsistencies. Underreporting violations causes health risks, and also unfairly provides some establishments with better inspection scores than they deserve. According to the data, inspectors found an average 2.4 violations per inspection. Thus, citing just one fewer or one more violation can lead to a 42 percent decrease or increase from the average—and great potential for unfair assessments across the food industry, where establishments are judged on their safety records by consumers and inspectors alike.

On average, inspectors cited fewer violations at each successive establishment inspected throughout the day, the researchers found. In other words, inspectors tended to find and report the most violations at the first place they inspected and the fewest violations at the last place.

The researchers chalked this up to gradual workday fatigue; it takes effort to notice and document violations and communicate (and sometimes defend) them to an establishment’s personnel.

“The more inspections you have done earlier in the day, the more tired you’re going to be and the less energy you’re going to have to discover violations,” Ibáñez says.

They also found that when conducting an inspection risked making the inspector work later than usual, the inspection was conducted more quickly and fewer violations were cited. “This seems to indicate that when inspectors work late, they are more prone to rush a bit and not be as meticulous,” Toffel says.

The level of inspector scrutiny also depended on whatever had been found at the prior inspection that day. In short, finding more violations than usual at one place seemed to induce the inspectors to exhibit more scrutiny at the subsequent place.

“This seems to indicate that when inspectors work late, they are more prone to rush a bit and not be as meticulous”

For example, say an inspector is scheduled to inspect a McDonald’s restaurant and then a Whole Foods grocer. Suppose McDonald’s had two violations the last time it was inspected. If the inspector now visits that McDonald’s and finds five or six violations, the inspector is likely to be particularly meticulous at the Whole Foods next on the schedule, reporting more violations than she otherwise would.

That behavior may be because inspectors put much effort into helping establishments learn the rules, create good habits, and improve food safety practices.

“It can be frustrating when establishments neglect these safety practices, which increases the risk of consumers getting sick,” Ibáñez says. “When inspectors discover that a place has deteriorated a lot, they’re disappointed that their message isn’t getting through, and because it poses a dangerous situation for public health.”

On the other hand, finding fewer violations than usual at one site had no apparent effect on what the inspector uncovered at the subsequent establishment. “When they find that places have improved a lot since their last inspection, they just move on without letting that affect their next inspection.”

Changes could improve public safety

The public health stakes are high for these types of errors in food safety inspections. The researchers estimate that tens of thousands of Americans could avoid food poisoning each year simply by reducing the number of establishments an inspector visits on a single day. Often, inspectors will cluster their schedule to conduct inspections on two or three days each week, saving the other days for administrative duties in the office. While this may save travel time and costs, it might be preventing inspectors from doing their jobs more effectively.

One possible remedy: Managers could impose a cap on the maximum number of inspections per day, and rearrange schedules to disperse inspections throughout the week—a maximum of one or two each day rather than three or four.

In addition, inspectors could plan early-in-the-day visits to the highest-risk facilities, such as elementary school cafeterias or assisted-living facilities, where residents are more vulnerable to the perils of foodborne illnesses than the general public.

On the plus side, tens of thousands of hospital bills are likely avoided every year, thanks to inspectors inadvertently applying more scrutiny after an unexpectedly unhygienic encounter at their previous inspection.

“Different scheduling regimes, new training, or better awareness could raise inspectors’ detection to the levels seen after they observe poor hygiene, which would reduce errors even more and result in more violations being detected, cited and corrected,” Ibáñez says.

The authors estimate that, if the daily schedule effects that erode an inspector’s scrutiny were eliminated and the establishment spillover effects that increase scrutiny were amplified by 100 percent, inspectors would detect many violations that are currently overlooked, citing 9.9 percent more violations.

“Scaled nationwide, this would result in 240,999 additional violations being cited annually, which would in turn yield 50,911 fewer foodborne illness-related hospitalizations and 19.01 million fewer foodborne illness cases per year, reducing annual foodborne illness costs by $14.20 billion to $30.91 billion,” the authors write.

Lessons for inspections

While the study focuses on food safety inspections, it offers broad lessons for any manager who has to manage or deal with inspections.

“One implication is that bias issues will arise, so take them into account as you look at the inspection reports as data,” Ibáñez says. “And another is that we should try to correct them. We should be mindful about the factors that may bias our decisions, and we should proactively change the system so that we naturally make better decisions.”

Additionally, FSIS is revising the definitions of antelope, bison, buffalo, catalo, deer, elk, reindeer, and water buffalo to make them more scientifically accurate.

Additionally, FSIS is revising the definitions of antelope, bison, buffalo, catalo, deer, elk, reindeer, and water buffalo to make them more scientifically accurate.