University of Würzburg researchers have used new technology to provide insight into how single Salmonella infect human cells. The study has just been published in “Nature Microbiology”.

Some bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella invade and replicate within human cells. Science is steadily shifting its focus towards studying infected cells and how differences between individual host cells affect the cellular response to pathogens.

Some bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella invade and replicate within human cells. Science is steadily shifting its focus towards studying infected cells and how differences between individual host cells affect the cellular response to pathogens.

A research team headed by Professor Jörg Vogel from the University of Würzburg has made significant progress in this area. They have developed a novel technique that allows them to investigate the interplay of individual host cells with infecting bacteria.

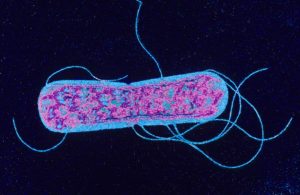

The team used a technique called “single-cell RNA-seq” to study the infection of macrophages by Salmonella. Macrophages are immune cells that belong to the group of white blood cells; Salmonella are pathogenic bacteria that may be taken up by the ingestion of contaminated water or food to cause local gastroenteritis and diarrhea. In immunocompromised patients however, Salmonella may disseminate throughout the entire body and cause life-threatening diseases.

Upon the invasion of macrophages, Salmonella pursue two strategies: The bacteria either replicate to high numbers inside the host cell or adopt a non-growing state that allows them to persist for years within the body of their host. “This disparate growth behavior impacts disease progression and plays a major role in the success of antibiotic treatment” says lead researcher Jörg Vogel.

To date, very little is known if and how macrophages respond to these disparate lifestyles of intracellular Salmonella. To answer this question the Würzburg scientists cultured macrophages in the laboratory and infected them with Salmonella.

The RNA from the infected cells was subsequently extracted and analyzed using deep-sequencing, leading to the detection of more than 5,000 different transcripts per macrophage. These data on the host’s gene expression were combined with information about the growth behavior of the intracellular pathogens.

The results: Macrophages containing non-growing bacteria adopt the hallmark signature associated with inflammation. They express signaling molecules to attract further immune cells to the site of infection. In this respect, they respond similarly to macrophages that have encountered Salmonella, but have not been infected. “These macrophages cannot detect their intracellular bacteria – they are below their radar” explains Emmanuel Saliba, first author of the study.

In contrast, macrophages with fast-growing bacteria develop an anti-inflammatory response. These interesting results open many questions, Do Salmonella induce this different response? Do they manipulate the macrophages so they do not raise the alarm to facilitate the bacteria to evade an immune response? Are there situations where Salmonella are unable to perform this trick? In these cases, will there still be an immune response forcing the bacteria to switch to their resting growth state?

“Currently we have just looked at a single time point after infection and thus cannot differentiate between cause and consequence” explains Alexander Westermann, another member of the team. Follow-up studies are required. Nevertheless, the current findings already provide a new perspective on the host response to pathogenic microbes. And using the new technology, bacterial infections can be studied in unprecedented resolution – namely on the single-cell level.