Restaurant inspection may only be a snapshot in time, and the grading or disclosure systems may have bureaucratic rules and seem unfair, but disclosure helps build a food safety culture, for the buying public and the back kitchen.

Lisa Fickenscher of Crain’s New York reports Waldy Malouf, the chef-owner of Beacon, has been asked by several concerned patrons about the “Grade Pending” sign posted in the restaurant’s entryway. One customer wanted a detailed explanation before she would book a party at the well-regarded midtown spot.

With the city reaching the one-year anniversary of the letter grading system, on July 28, New Yorkers have come to rely on the prominently .png) displayed signs. And many say the grades influence their decision whether to dine at an establishment.

displayed signs. And many say the grades influence their decision whether to dine at an establishment.

This week, Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley will mark the system’s first year by releasing results of the program. And if the agency’s previous findings are an indication, the majority of New York’s 24,000-plus restaurants will have earned an A.

The grades are “something the public wants,” said Anthony Dell’ Orto, owner of Manganaro’s Hero Boy. “You’d be antagonizing your own customers” to oppose the system, said Mr. Dell’Orto, whose Hell’s Kitchen eatery received an A.

The city has hailed the grades as a success by several measures. Officials point out that though just 27% of restaurants earned an A on the first inspection, in a second round for those with lower grades, a majority had improved enough to earn an A.

“We are more vigilant and diligent,” said Andrew Schnipper, co-owner of Schnipper’s Quality Kitchen, a cafeteria-style American food joint in Times Square that was recently awarded a top grade.

To gain his stripes, Mr. Schnipper ramped up efforts to keep his place immaculate and in compliance with the health code. That meant a checklist with items ranging from ensuring that refrigerators are equipped with thermometers to checking that bathrooms always have soap and paper towels.

Though forced to abide by the rules, most owners view the system as unfair. They argue that it is a cash cow for a revenue-starved city—in addition to a flawed snapshot of their businesses. Even operators who boast an A are skeptical about the grades’ effectiveness as an appropriate measure.

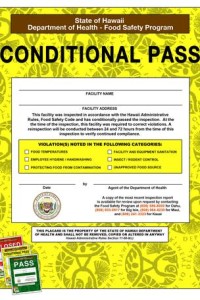

The Hawaii Tribune Herald reports big changes are coming to the way the state Department of Health inspects and evaluates food .jpg) establishments. Soon, the public will know at a glance how a restaurant, school cafeteria or other food service establishment fared in its most recent inspection.

establishments. Soon, the public will know at a glance how a restaurant, school cafeteria or other food service establishment fared in its most recent inspection.

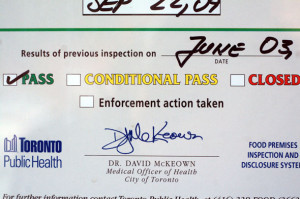

The grading system will be green, yellow and red cards – similar to the program used in Toronto — prominently posted in public view in the eating establishment.

The cards will be paired with an online restaurant inspection reporting system that will allow the public to see the inspection reports simply by selecting the name of a restaurant.

The Department of Health is formulating new rules and will hold public hearings on all the islands before they are adopted. The inspection system overhaul includes an update to the FDA’s 2009 food safety standards. Many governments are using the 2001 and 2005 food codes; Hawaii is using the 1991 code, Oshiro said.

If all goes as planned, the new system could be in place on Oahu by the beginning of next year, and on the Neighbor Islands by next spring.

The importance of restaurant inspections can’t be underestimated, said Douglas Powell, professor of food safety in the Kansas State University Department of Diagnostic Medicine/Pathobiology and one of the authors of barfblog.com, a blog about food safety.

"Public disclosure of inspection information helps foster a culture of food safety by encouraging dialogue about food safety concerns among both consumers, various levels of government and the food service industry," he said.

“One of the big problems was when the inspectors used the system in the field, it freezes up, it was very slow, and that was very frustrating for our staff,” explained Peter Oshiro, DOH environmental health program manager.

“One of the big problems was when the inspectors used the system in the field, it freezes up, it was very slow, and that was very frustrating for our staff,” explained Peter Oshiro, DOH environmental health program manager.

.jpg)

particularly Hawaiian hogs and chickens. However, a search of the literature did not find data to implicate the local deer population as a source for foodborne illness.”

particularly Hawaiian hogs and chickens. However, a search of the literature did not find data to implicate the local deer population as a source for foodborne illness.”.png) displayed signs. And many say the grades influence their decision whether to dine at an establishment.

displayed signs. And many say the grades influence their decision whether to dine at an establishment..jpg) establishments. Soon, the public will know at a glance how a restaurant, school cafeteria or other food service establishment fared in its most recent inspection.

establishments. Soon, the public will know at a glance how a restaurant, school cafeteria or other food service establishment fared in its most recent inspection.