Science is about disagreements, revising knowledge and generating new evidence-based knowledge (someone will disagree with that).

Don Sapatkin of the Philadelphia Inquirer recently asked a number of food safety types about food safety at home. For fun, I asked friend of the barfblog and known bugcounter, Don Schaffner of Rutgers University (left, prettymuch as shown) his thoughts on the answers.

Don Sapatkin of the Philadelphia Inquirer recently asked a number of food safety types about food safety at home. For fun, I asked friend of the barfblog and known bugcounter, Don Schaffner of Rutgers University (left, prettymuch as shown) his thoughts on the answers.

“Washing a sponge with soap doesn’t get rid of bacteria,” said microbiologist Michael Doyle, director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Food Safety (below, right). They grow at room temperature and get spread around anything else you wipe off. Put the sponge in a microwave for one minute to kill the salmonella and other bacteria,” he said.

Schaffner: Sort of true. Washing a sponge will probably remove some bacteria, but not all. Same with the microwave: it depends upon the microwave, the amount of moisture in the sponge, etc. A better practice may be to put your sponges in the automatic dishwasher, assuming you have one.

Experts say most home kitchens are far dirtier.

Schaffner: Might be true, but science-based head-to-head comparisons are lacking.

Cutting boards should not have hard-to-clean nicks and grooves (wood is better, Doyle said, because the resin has antibacterial properties).

Schaffner: Dean Cliver’s work showed wooden cutting boards to be safer, but the literature is far from clear on the matter.

Washing chicken in the sink may sound hygienic but actually poses all sorts of risks.

Schaffner: Yup, this has good scientific consensus.

“Every time you run your disposal in the sink you are generating a little airflow back up.”

Schaffner: Yup, probably true.

Schaffner: Yup, probably true.

If you do wash chicken in the sink, clean it (the sink) with bleach (1 ounce in 1 gallon of water).

Schaffner: Giving bleach concentration recommendations always concerns me. The units are never the same, the knowledge about the type of bleach is never certain, and the type of surface being cleaned makes a difference (plates versus countertops). I used to dream of creating a webpage that would definitively answer these questions, and do unit conversions. Now I have the same dream except it’s an iPhone app.

Craig Hedberg, a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health (below, left): “If you take this big mass of hot food and put it into a plastic container and put a lid on it, you are holding the heat in and slowing the cooling process, even if you put it in the refrigerator. You want to get it out of bacterial-growth range” – 40 to 140 degrees – “within a couple of hours.” Pouring it into containers no more than four inches deep speeds the process.

Schaffner: This is more or less correct, but I believe the correct depth of the food recommendation is 3 inches. It doesn’t really matter how deep the container is, it’s the depth of the food.

If food is not cooled fast enough, spores that survived cooking can germinate and grow bacteria. Reheating leftovers to 165 degrees for 15 seconds will kill them.

Schaffner: This is the general time temperature recommendation. I’ve never checked to see what log reduction it would give for Clostridium perfringens cells, but it’s likely sufficient.

Hedberg advises against washing prewashed bagged lettuce; E. coli and salmonella can adhere to cut surfaces and tiny pores. “If it’s contaminated, your washing it again would not eliminate the contamination,” he said. “If it is not contaminated, your washing may contaminate it.”

Schaffner: That is consistent with expert recommendations.

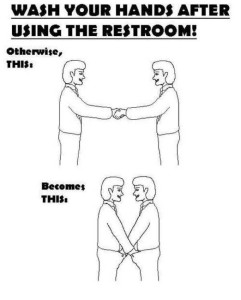

Hands should be washed vigorously with soap before preparing food or eating; after handling raw meat, poultry, fish, or even raw produce; and after smoking, eating, or drinking.

Schaffner: Also after pooping or changing a diaper, handling pets etc.

Schaffner: Also after pooping or changing a diaper, handling pets etc.

Countertops, cutting boards, utensils, etc., should be cleaned with hot water after every use.

Schaffner: I also recommend soap.

Cooking and holding temperatures should be checked, which means having working thermometers. (The fridge should be set between 32 and 40 degrees Fahrenheit; the freezer, at zero or below).

Schaffner: They nailed this one.

Everything should be clean: Garbage covered, or at least three feet from food-preparation areas; pets never allowed in the kitchen (and hands washed after petting).

Schaffner: I’m not sure where the three-foot recommendation comes from, and it’s probably not science-based. Does anyone really exclude their pets from the kitchen? When we had dogs their food and water dishes were in the kitchen. Good luck getting a cat to do anything you want to do.

To bring home cooks up to speed, the Rutgers University Cooperative Extension posts a quick home kitchen food safety best practices check-Up list: http://bit.ly/1xDO19F.

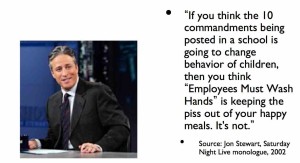

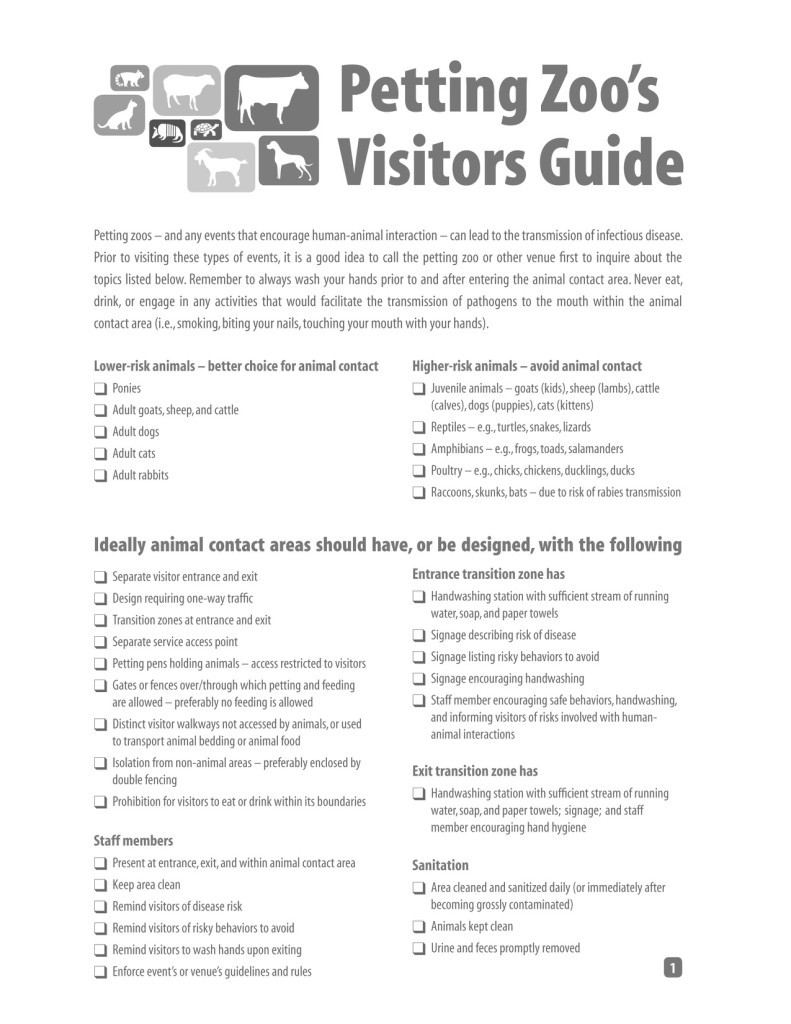

This research collects and reviews existing handwashing signs and subjects them to quantitative analysis. An Internet search produced a database of handwashing signs. Lather time, rinse time, overall wash time, water temperature, water use, drying method, technique, and total number of steps were recorded.

This research collects and reviews existing handwashing signs and subjects them to quantitative analysis. An Internet search produced a database of handwashing signs. Lather time, rinse time, overall wash time, water temperature, water use, drying method, technique, and total number of steps were recorded.