Restaurateurs had their moment in the New York City political sun today, and wasted the opportunity with a barrage of complaints about the unfairness of restaurant inspections as well as the letter grades.

They could have said, most of us take food safety seriously, we’re proud of our establishments, so proud that we want to work with health types to make the system better, and we want to brag about our great food safety.

More representative of the 300 people who filled a City Council chamber today was Dimitri Kafchitsas, who heads a group of 1,000 restaurants in New York City: The average food-safety .png) visit “feels like a criminal raid and not an inspection. There is a lack of sensitivity.”

visit “feels like a criminal raid and not an inspection. There is a lack of sensitivity.”

More sensitivity and less in-your-face? In New York City?

NYC could have saved itself some grief by doing some significant consumer and food service research before launching the system and figuring out what kind of disclosure would work best for New Yorkers (we did this in New Zealand).

A major criticism from restaurateurs has been the city’s imposition of significant fines for issues that they say have no bearing on food safety. Among them have been fines for inadequate lighting, employees’ drinking beverages while on duty, leaky faucets, leaky faucets, broken tiles and open doors.

Risk-based, consistent inspections are a problem in every municipality and state. Work on it; improve the system. But don’t just whine.

The City’s health commissioner Thomas Farley told the hearing (from a prepared statement), “I know that you will hear complaints today from some restaurant owners. But just imagine this scenario: Salmonella cases are up 14 percent; the number of restaurants with rodents has increased by 50 percent and viral videos of rats in kitchens dominate the web; and restaurant sales are plummeting.

What would happen? The Council would hold a hearing and demand to know why the Health Department wasn’t doing its job. You would describe horror stories of constituents getting sick, and you would demand swift action. And you would be right, because my job is to protect the health of New Yorkers.

Fortunately, the opposite scenario is happening right now. Since restaurant grading began, salmonella cases are down 14 percent. The Department’s website shows that 72 percent of restaurants have received the top grade for cleanliness. Restaurant sales are up almost 10% since grading began, increasing by $800 million. And 91 percent of New Yorkers say they support restaurant grading.”

Daniel E. Ho, a professor of law at Stanford and a visiting professor of law at Yale this spring, takes a stab at suggestions for improvement, writing in the New York Times this morning that the well-intentioned system is broken.

“Along with researchers at New York University, Stanford and Yale law schools, I have studied data from more than 500,000 inspections of more than 100,000 restaurants from the last few years in nine jurisdictions: Austin, Tex.; Catawba County, N.C.; Chicago; El Paso; Florida; Louisville, Ky.; New York City; San Diego; and Seattle. Our research examined the process for tallying violations and the consistency of inspections across repeat, unannounced visits to the same restaurant. In a critical dimension, New York performed the worst of the nine.

At their core, the inspections work similarly across the jurisdictions. From once to a few times a year, a health inspector shows up unannounced to tally health code violations, like failure to wash hands or to maintain food temperatures. If violations amount to a public health hazard, the restaurant may be shut down until they are resolved.

“Our examination found key deficiencies in New York’s inspection system.

First, the score a restaurant gets in New York says little about how it will perform in the future. Grades are based on a point system: in New York, 0 to 13 points yields an A, 14 to 27 points a B, and 28 or more points a C. In other jurisdictions, numerical scores substantively predict future  scores. In San Diego, for example, prior scores account for roughly 25 percent of the variation in future scores. But New York is an outlier: Prior scores predict less than 2 percent of the variation in future scores. New York City’s posted restaurant grades therefore fail the most basic criterion: they communicate little about future cleanliness.

scores. In San Diego, for example, prior scores account for roughly 25 percent of the variation in future scores. But New York is an outlier: Prior scores predict less than 2 percent of the variation in future scores. New York City’s posted restaurant grades therefore fail the most basic criterion: they communicate little about future cleanliness.

Why such inconsistency? Although the jurisdictions share broad similarities, the details of New York’s inspection process are far more complex. There are more inspectors (some 180, not all of whom necessarily specialize full time in restaurant inspections), more violations to score and far wider point ranges for each violation.

“While San Diego, for example, has a single violation for vermin, New York records separate violations for evidence of rats or live rats; evidence of mice or live mice; live roaches; and flies — each scored at 5, 6, 7, 8 or 28 points, depending on the evidence. Thirty “fresh mice droppings in one area” result in 6 points, but 31 droppings result in 7 points.

“To reduce imprecision, the city should apply the key insight of grading — simplification — not only for information consumers, but also for information producers — i.e., the inspectors. To increase efficiency, the city should abandon inspections for the purpose of resolving grades and instead redeploy those resources to focus on the worst offenders. It’s time for grade reform.”

OK. Get on with it. Restaurant managers, health types and consumers need to figure out how best to improve the system. But disclosure is here to stay.

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2011. Designing a national restaurant inspection disclosure system for New Zealand?. Journal of Food Protection 74(11): 1869-1874?.

http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iafp/jfp/2011/00000074/00000011/art00010?The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from contaminated food or water each year, and up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food service facilities. The aim of restaurant inspections is to reduce foodborne outbreaks and enhance consumer confidence in food service. Inspection disclosure systems have been developed as tools for consumers and incentives for food service operators. Disclosure systems are common in developed countries but are inconsistently used, possibly because previous research has not determined the best format for disclosing inspection results. This study was conducted to develop a consistent, compelling, and trusted inspection disclosure system for New Zealand. Existing international and national disclosure systems were evaluated. Two cards, a letter grade (A, B, C, or F) and a gauge (speedometer style), were designed to represent a restaurant’s inspection result and were provided to 371 premises in six districts for 3 months. Operators (n = 269) and consumers (n = 991) were interviewed to determine which card design best communicated inspection results. Less than half of the consumers noticed cards before entering the premises; these data indicated that the letter attracted more initial attention (78%) than the gauge (45%). Fifty-eight percent (38) of the operators with the gauge preferred the letter; and 79% (47) of the operators with letter preferred the letter. Eighty-eight percent (133) of the consumers in gauge districts preferred the letter, and 72% (161) of those in letter districts preferring the letter. Based on these data, the letter method was recommended for a national disclosure system for New Zealand.

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2009. The use of restaurant inspection disclosure systems as a means of communicating food safety information. Journal of Foodservice 20: 287-297.

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from food or water each year. Up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food prepared at foodservice establishments. Consumer confidence in the safety of food prepared in restaurants is fragile, varying significantly from year to year, with many consumers attributing foodborne illness to foodservice. One of the key drivers of restaurant choice is consumer perception of the hygiene of a restaurant. Restaurant hygiene information is something consumers desire, and when available, may use to make dining decisions.

.jpg) going to eat at restaurants with a “C.”

going to eat at restaurants with a “C.”

(2).png) simply inspect for things is because it takes too long."

simply inspect for things is because it takes too long.".png) inspection grades keeps everyone awake

inspection grades keeps everyone awake(1)(1).jpg) not. Many other states also insist inspections be posted at the restaurant itself; Louisiana does not.

not. Many other states also insist inspections be posted at the restaurant itself; Louisiana does not.(1)(1).jpg) Tenney Sibley, chief of sanitarian services for the DHH, said more information — such as ratings or grades — are unnecessary.

Tenney Sibley, chief of sanitarian services for the DHH, said more information — such as ratings or grades — are unnecessary.(1)(2).jpg) confidence in the safety of food prepared in restaurants is fragile, varying significantly from year to year, with many consumers attributing foodborne illness to foodservice. One of the key drivers of restaurant choice is consumer perception of the hygiene of a restaurant. Restaurant hygiene information is something consumers desire, and when available, may use to make dining decisions.

confidence in the safety of food prepared in restaurants is fragile, varying significantly from year to year, with many consumers attributing foodborne illness to foodservice. One of the key drivers of restaurant choice is consumer perception of the hygiene of a restaurant. Restaurant hygiene information is something consumers desire, and when available, may use to make dining decisions.(1)(1).png) not get an award.

not get an award..jpg) conditions.

conditions. .jpg) Wales, which includes Sydney, ACT and the federal capital of Canberra can apparently make its own rules – at least regarding restaurant inspection disclosure.

Wales, which includes Sydney, ACT and the federal capital of Canberra can apparently make its own rules – at least regarding restaurant inspection disclosure..png) warm fridges.

warm fridges. 2012. A "traffic light" scheme will show which eateries are spick-and-span — and which have nasties lurking under the cupboards.

2012. A "traffic light" scheme will show which eateries are spick-and-span — and which have nasties lurking under the cupboards..jpg) national association of consumer initiatives said.

national association of consumer initiatives said..jpg) displayed at business premises.

displayed at business premises..png) currently have a written procedure for food hygiene. Whilst the business premises could be spotless, without this written supporting document they could not be scored above a one-star rating. It is important to note that those premises with low ratings are most likely to be in the process of improving."

currently have a written procedure for food hygiene. Whilst the business premises could be spotless, without this written supporting document they could not be scored above a one-star rating. It is important to note that those premises with low ratings are most likely to be in the process of improving."_story.jpg) the first six months under the new rules, 87 per cent had received either A or B grades, and 57 percent had received A’s.

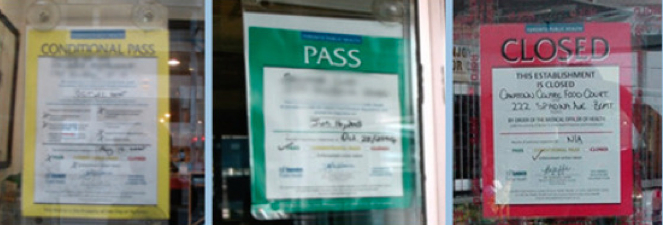

the first six months under the new rules, 87 per cent had received either A or B grades, and 57 percent had received A’s.(1)(1).jpg) premise that receives a yellow conditional pass is re-inspected within 48 hours. Depending on the type of operation, each premise requires between one and three mandatory inspections a year.

premise that receives a yellow conditional pass is re-inspected within 48 hours. Depending on the type of operation, each premise requires between one and three mandatory inspections a year.