People want to know what’s in (or on) their food.

Some people care about different things: I care about the microbes that make people barf.

But when people buy food at a grocery store, restaurant or market, they don’t really know what they’re getting, because “food  safety is the number 1 priority” or “we’ve done it this way for years and never made anyone sick” or “trust me.”

safety is the number 1 priority” or “we’ve done it this way for years and never made anyone sick” or “trust me.”

One attempt to fill that gap is making the results of food inspections public. It’s popular with local voters, and similarly popular with media.

The New Zealand Herald is the latest to embrace the dirty dining trend, running daily summaries of the worst offenders.

New Zealand has a hodgepodge of inspection disclosure systems, so the series focuses on the biggest city, Auckland, which does have a letter grading system.

Last month Central Auckland’s dirtiest eating establishments were named.

Food grades in the former Auckland City region show 10 restaurants and cafes have received E grades, with 29 given a D grade.

The New Zealand Herald online asked readers if they were influenced by the food grading system. Nearly 13,500 readers responded and just over half said they used the rating to make a call about whether to dine there. Or not.

But to the every day diner, how do these places really stack up?

A few brave members of the online team have decided to put their bellies on the line and review all 29 of the D listers, revealing one a day for the month of September. D grade eateries are reviewed twice a year, according to Auckland City Council. While they are  subject to change, our list is correct as of the last week of August, 2013. If the grade is changed at the time of publication this will be made clear in the review.

subject to change, our list is correct as of the last week of August, 2013. If the grade is changed at the time of publication this will be made clear in the review.

In capital city Wellington, city council records given reluctantly to Fairfax NZ show 38 premises were issued with cleaning or repair notices in the past financial year, including four that were forced to close.

The list of notices is publicly available information but it was released only after the council told the businesses on the list that it was “extremely reluctant” to provide their names.

Council operations and business development team leader Raaj Govinda said in a letter sent to all premises before the list was released, council was not able to withhold names from the public, though it was “extremely reluctant” to provide the list and “has not done so willingly.”

That will do nothing to build consumer confidence.

Other councils, including Auckland and Palmerston North, list the hygiene ratings for all eateries online.

Yesterday, Govinda said Wellington was considering doing that but it did not want to put businesses at risk.

“In general, council is not in the business of trying to close people. We have got a regulatory duty.”

But unlike the U.S. version of the restaurant lobby, Wellington Restaurant Association president Mike Egan said it was important for restaurants to be held accountable, as closure notices were often a last resort, adding, “Those places would have had ample opportunity normally to put things right and it’s about a failure to either take it seriously or react appropriately.” Putting ratings online could be a “big carrot” for good practice, he said.

We have some experience with restaurant inspection disclosure systems. Even in New Zealand.

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2011. Designing a national restaurant inspection disclosure system for New Zealand.

Journal of Food Protection 74(11): 1869-1874

.

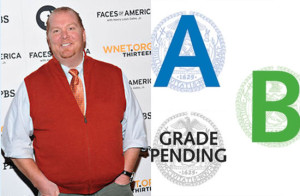

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from contaminated food or water each year, and up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food service facilities. The aim of restaurant inspections is to reduce foodborne outbreaks and enhance consumer confidence in food service. Inspection disclosure systems have been developed as tools for consumers and incentives for food service operators. Disclosure systems are common in developed countries but are inconsistently used, possibly because previous research has not determined the best format for disclosing inspection results. This study was conducted to develop a consistent, compelling, and trusted inspection disclosure system for New Zealand. Existing international and national disclosure systems were evaluated. Two cards, a letter grade (A, B, C, or F) and a gauge (speedometer style), were designed to represent a restaurant’s inspection result and were provided to 371 premises in six districts for 3 months. Operators (n = 269) and consumers (n = 991) were interviewed to determine which card design best communicated inspection results. Less than half of the consumers noticed cards before entering the  premises; these data indicated that the letter attracted more initial attention (78%) than the gauge (45%). Fifty-eight percent (38) of the operators with the gauge preferred the letter; and 79% (47) of the operators with letter preferred the letter. Eighty-eight percent (133) of the consumers in gauge districts preferred the letter, and 72% (161) of those in letter districts preferring the letter. Based on these data, the letter method was recommended for a national disclosure system for New Zealand. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iafp/jfp/2011/00000074/00000011/art00010

premises; these data indicated that the letter attracted more initial attention (78%) than the gauge (45%). Fifty-eight percent (38) of the operators with the gauge preferred the letter; and 79% (47) of the operators with letter preferred the letter. Eighty-eight percent (133) of the consumers in gauge districts preferred the letter, and 72% (161) of those in letter districts preferring the letter. Based on these data, the letter method was recommended for a national disclosure system for New Zealand. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/iafp/jfp/2011/00000074/00000011/art00010

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2009. The use of restaurant inspection disclosure systems as a means of communicating food safety information. Journal of Foodservice 20: 287-297.

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from food or water each year. Up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food prepared at foodservice establishments. Consumer confidence in the safety of food prepared in restaurants is fragile, varying significantly from year to year, with many consumers attributing foodborne illness to foodservice. One of the key drivers of restaurant choice is consumer perception of the hygiene of a restaurant. Restaurant hygiene information is something consumers desire, and when available, may use to make dining decisions.

(1).png)

safety assessments more readily accessible to the public.

safety assessments more readily accessible to the public.