Apparently I wasn’t imagining when I wrote the Spongebob cone of silence – usually reserved for leafy greens, cantaloupes and sometimes tomatoes — had finally been lifted on an E. coli O157 outbreak involving raw milk in California.

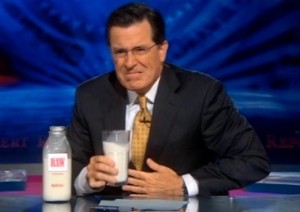

Organic Pastures Dairy in Fresno County voluntarily recalled its raw milk in Jan. 2016 after internal tests found evidence of E. coli. The tainted milk caused at least 10 illnesses, with six of those victims reporting they drank Organic Pastures raw milk, said California Department of Public Health officials on Mar. 1, 2016.

Organic Pastures Dairy in Fresno County voluntarily recalled its raw milk in Jan. 2016 after internal tests found evidence of E. coli. The tainted milk caused at least 10 illnesses, with six of those victims reporting they drank Organic Pastures raw milk, said California Department of Public Health officials on Mar. 1, 2016.

The victims all had closely related strains of E. coli O157, the health department said.

Dairy owner Mark McAfee said that in early January the company voluntarily recalled the milk within 36 hours of determining the presence of E. coli.

At the time of the last announcement, CDPH types told Healthy Magician the state health department is continuing to investigate the outbreak, but will not provide specific details.

“The environmental investigation is ongoing. CDPH has collected a large number of samples including feces, water and raw milk, which are still undergoing evaluation at the department’s Food and Drug Laboratory Branch,” the CDPH spokesman said via email.

When they are available, the department will not release them until the investigation is finished, the CDPH spokesman said last Tuesday.

The department has not published any statements about the outbreak or investigation.

“CDPH does not routinely post in-process updates on its active investigations,” the department’s spokesman said via email. “If the public needs to be alerted about an adulterated food, CDPH will issue a Health Advisory warning consumers of the food that should be avoided.

“In this case, the outbreak was identified and the voluntary recall issued by the firm after the shelf-life of the product had expired. Since no product was believed to remain in the marketplace, no health alert was issued.”

“In this case, the outbreak was identified and the voluntary recall issued by the firm after the shelf-life of the product had expired. Since no product was believed to remain in the marketplace, no health alert was issued.”

However, legal eagle Bill Marler got his hands on a summary of the investigation dated March 3, 2013. The report concludes:

Evidence collected to date, indicates that cattle in the OPDC milking herd were shedding E. coli O157 that matched PFGE patterns associated with ten illnesses in January 2016. In early January 2016, Cow 149 produced milk contaminated with E. coli O157 which may have been bottled and shipped to the public. Feces, soil, and water collected from OPDC on February 8, 2016 tested positive for E. coli O157:H7, and PFGE patterns for those isolates also matched those patterns associated with the illnesses. The collection of environmental samples from OPDC on February 8, 2016 focused on feces likely deposited on February 6, 7, and 8. It is unlikely that the positive findings from February 8, 2016 represent conditions linked entirely to Co 149. The isolation of E. coli O157:H7 and non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing E. coli from cattle used to produce raw milk for human consumption is concerning and could result in additional illness to raw milk consumers in the future if not addressed at the dairy.