In 2013, European governments launched a massive investigation after food-safety agencies discovered that an alarming number of products advertised as beef were actually horsemeat.

In China last year, Wal-Mart recalled its “Five Spice” donkey-meat snacks after they were found to be adulterated with fox meat. In the U.S., Americans spend around $5.57 billion a year on sausages—but up to 14 percent of the time, the type of meat may not match what’s advertised on the package.

In China last year, Wal-Mart recalled its “Five Spice” donkey-meat snacks after they were found to be adulterated with fox meat. In the U.S., Americans spend around $5.57 billion a year on sausages—but up to 14 percent of the time, the type of meat may not match what’s advertised on the package.

That last statistic comes from Clear Labs, a startup that aims to quite literally see how the sausage gets made. The company, which uses DNA sequencing to analyze the contents of food, claims its molecular database of around 10,000 items is the largest in the world—a tool it plans to use to fight food fraud, which currently affects an estimated 10 percent of the world’s commercial food supply. Earlier this month, it launched a Kickstarter campaign for its new consumer initiative Clear Food, a project to analyze and publish a report on a particular food category each month (backers will get to vote on the category they’d like Clear Labs to tackle next). Each product included in the report will receive a score based on how closely the label matches the content.

According to Martin Wiedmann, a professor of food safety at Cornell University, the FDA primarily focuses its efforts on keeping food uncontaminated, rather than the accuracy of labeling.

“The FDA does not have unlimited resources, but to be honest, I’d rather the FDA do more work on food safety than making sure that red snapper doesn’t happen to be tilapia,” he said. “I think private industry will play a very, very important role in this issue.”

So does Clear Labs. The company was founded in 2013 by Sasan Amini and Ghorashi in 2013, both of whom left their jobs at genomics companies to apply DNA-testing technologies to the food industry. The process is similar to the genomic analysis used in clinical trials to personalize cancer treatments—when a hot-dog package proclaims the contents to be “all beef,” Clear Labs’ analysis can compare the molecular makeup of that hot dog against the molecular signature of beef, stored in the database, to see if it’s true. The company says it can also determine whether the label’s nutritional claims are valid.

“Once we started to test the U.S. food supply in a rigorous fashion, we started to see a 10-15 percent discrepancy rate between product claims and actual molecular content of the food,” Ghorashi said.

In the Clear Foods initiative’s report on hot dogs and sausages, the company analyzed 345 samples across 75 brands and 10 retailers, and found that 14.4 percent of the products tested were “problematic in some way.”

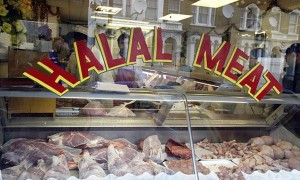

Around 3 percent of the samples found pork where it shouldn’t have been, most often in meats labeled as chicken or turkey, and around 10 percent of the vegetarian products contained meat. Vegetarian products seemed to have the most problems across the board: Four of the 21 vegetarian samples had hygienic issues (accounting for two-thirds of the hygienic issues found in the report), and many vegetarian labels exaggerated the protein content by up to 2.5 times the actual amount.

“We expected to find some deviations because it is a complex supply chain,” Ghorashi said, “but this is also about intentional adulteration for economic gain, which is basically fraud.”

Weidmann said that while molecular sequencing of food can inject more transparency into the food system, there are also significant challenges to consider. For example, DNA testing often yields false positives. And as tests have become more sensitive, cross-contamination poses a great risk to the results.

A judge last week granted final approval to a settlement of a class-action suit filed against Subway after an Australian teenager posted an image on Facebook of a sandwich that was a mere 11 inches.

A judge last week granted final approval to a settlement of a class-action suit filed against Subway after an Australian teenager posted an image on Facebook of a sandwich that was a mere 11 inches.