News21 is part of a national Knight-Carnegie university reporting project that worked on a bunch of food safety stories over the summer. I spent a lot of time on the phone with these students, as did many others. One of the results was published in the Washington Post over the weekend; excerpts below.

On a late June morning, thousands of newborn chicks in a West Virginia chicken house huddled together for warmth, forming a fuzzy, moving yellow carpet.

Over the next two months, these chicks pecked at the dirt, nibbled on pellets, grew up. They were packed into crates, trucked to a slaughterhouse, cut into parts and sent to a distribution center for .jpg) shipment to supermarkets and restaurants.

shipment to supermarkets and restaurants.

At every step along the way, some of those chickens were infected with salmonella, a pathogen that lives in the intestinal tracts of birds and other animals and can easily spread. Invisible, tasteless and odorless, it doesn’t make the chickens sick. But transferred to humans, it can lead to salmonellosis — an infection that causes diarrhea, fever and stomach cramps, and, in severe cases, can spread from the intestines to the bloodstream.

A look at how the nation’s food safety system operates in the case of salmonella-infected poultry shows how a combination of industry practices and gaps in government oversight results in a fractured effort that leaves the ultimate responsibility for safe food with the consumer.

Food safety experts and poultry scientists say that salmonella control must start on the farm, but federal food safety inspectors never set foot there. The Agriculture Department’s Food Safety and Inspection Service lacks the legal authority to test for salmonella on farms or to require farmers to have a food safety plan.

As a result, attempts to prevent salmonella are done voluntarily by farmers or because poultry processing companies ask them to — leading to a patchwork of efforts, some of which work better than others.

Stan Bailey, a retired USDA microbiologist, said that during his career, he noticed that some companies worked harder than others on food safety. “I think different people have different attitudes on how much they’re willing to spend,” he said.

And no matter how much salmonella USDA finds in raw meat, it cannot be kept off the market.

.jpg)

(10).jpg) cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.”

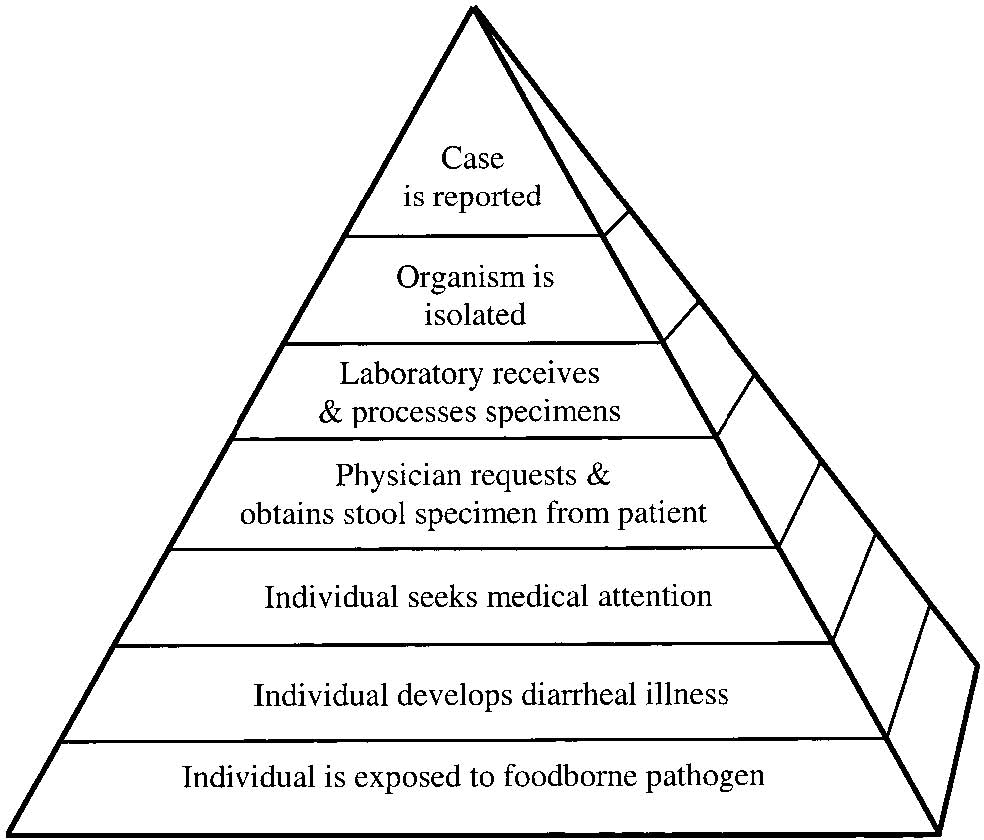

cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.” burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.

burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.