Chapman wasn’t feeling particularly hysterical as he kept crapping himself while he was in Manhattan (Kansas) a couple of weeks ago and was then confirmed to be suffering from campylobacter.

.jpg) I didn’t feel hysterical with my own case of the green apple splatters over the weekend while sitting in the backseat with Sorenne, as Amy drove the five hours to Lebannon, Missouri, for a Thanksgiving dinner with her father and family. I spent the six hours we were there in the bed or bathroom, along with the five hour drive home, topped off with an, uh, uncomfortable night.

I didn’t feel hysterical with my own case of the green apple splatters over the weekend while sitting in the backseat with Sorenne, as Amy drove the five hours to Lebannon, Missouri, for a Thanksgiving dinner with her father and family. I spent the six hours we were there in the bed or bathroom, along with the five hour drive home, topped off with an, uh, uncomfortable night.

Parents of children who have died from foodborne illness, like Mason Jones of the U.K., are not hysterical. I prefer to discuss the multiple food safety failures that led to the outbreak so that others can be prevented – fewer sick people, fewer grieving parents. That’s not hysterical.

And the three people who have been stricken with E. coli O157 linked to drinking raw, unpasteurized milk from the Dungeness Valley Creamery in Washington State, reported this afternoon by the Washington State Department of Health, probably don’t feel they are being hysterical.

No E. coli has been found in samples from the dairy’s current batch of milk, but during an investigation at the dairy, WSDA found the same bacteria that caused one of the illnesses.

.jpg) That, according to would-be raw milk guru David Gumpert, would probably mean health types were being hysterical because they didn’t have better proof of causation.

That, according to would-be raw milk guru David Gumpert, would probably mean health types were being hysterical because they didn’t have better proof of causation.

While acknowledging in some sort of column-opinion piece released last week that there are tragic cases, Gumpert attempted to blow the lid off the foodborne-illness-sick-people-hype by saying the data are incomplete and then sets up the rhetorical strawperson thingy:

“So what’s behind the hysteria on foodborne illness? Clearly, part of it has to do with the dramatic cases being reported of individuals who have suffered serious long-term repercussions. … They are tragic.”

I wrote a book with a professor who liked to begin every other paragraph with, “Clearly …” Maybe with the perspective of hindsight things are clear, but when outbreaks are actually going on, things are confusing. I’m much more comfortable saying, “I don’t know, how can we find out more,” rather than, “Clearly.”

We didn’t write together again.

Gumpert also said in his piece last week, “But there’s another factor at work here as well: a drive to broadly expand the powers of the FDA.”

The government conspiracy angle.

Gumpert apparently has issues with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and says “if you examine the data on foodborne illness, you find a different sort of crisis—a crisis of credibility, based on ineffective and incomplete data gathering and investigation.”

It’s been that way for a long time, because of the uncertainties of investigating the incidence and causes of foodborne illness.

The FoodNet surveillance system was established within the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in 1995 to determine more precisely and to monitor better the burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.

For every known case of foodborne illness, there are 10 -300 other cases, depending on the severity of the bug.?????? Most foodborne illness is never detected. It’s almost never the last meal someone ate or whatever other mythologies are out there. A stool sample linked with some epidemiology or food testing is required to make associations with specific foods.

For every known case of foodborne illness, there are 10 -300 other cases, depending on the severity of the bug.?????? Most foodborne illness is never detected. It’s almost never the last meal someone ate or whatever other mythologies are out there. A stool sample linked with some epidemiology or food testing is required to make associations with specific foods.

Foodborne illness is vastly underreported – it’s known as the burden of reporting foodborne illness, or the burden of illness pyramid (right), a model for understanding foodborne disease reporting. Someone has to get sick enough to go to a doctor, go to a doctor that is bright enough to order the right test, live in a State that has the known foodborne illnesses as a reportable disease, and then it gets registered by the feds. All of this happened for Chapman’s campylobacter.

FoodNet additionally conducts laboratory surveys, physician surveys, and population surveys to collect information about each of these steps.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that up to 30 per cent of individuals in developed countries acquire illnesses from the food and water they consume each year. U.S., Canadian and Australian authorities support this estimate as accurate (Majowicz et al., 2006; Mead et al., 1999; OzFoodNet Working Group, 2003) through estimations from available data, active disease surveillance and adjustments for underreporting. WHO has identified five factors of food handling that contribute to these illnesses: improper cooking procedures; temperature abuse during storage; lack of hygiene and sanitation by food handlers; cross-contamination between raw and fresh ready to eat foods; and, acquiring food from unsafe sources.

Putative food safety legislative changes involving FDA set a minimal bar for food safety; it can be improved, but the best food producers and processors will go far beyond government standards, provide testing data and market food safety directly to consumers at retail – but only if the data exists to validate such claims.

Majowicz, S.E., McNab, W.B., Sockett, P., Henson, S., Dore, K., Edge, V.L., Buffett, M.C., Fazil, A., Read, S. McEwen, S., Stacey, D. and Wilson, J.B. (2006), “Burden and cost of gastroenteritis in a Canadian community”, Journal of Food Protection, Vol. 69, pp. 651-659. ??????

Mead, P.S., Slutsjer, L., Dietz, V., McCaig, L.F., Breeses, J.S., Shapiro, C., Griffin, P.M. and Tauxe, R.V. (1999), “Food-related illness and death in the United States”, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol. 5, pp. 607-625.

OzFoodNet Working Group. (2003), “Foodborne disease in Australia: Incidence, notifications and outbreaks: Annual report of the OzFoodNet Network, 2002”, Communicable Diseases Intelligence, Vol. 27, pp. 209-243.

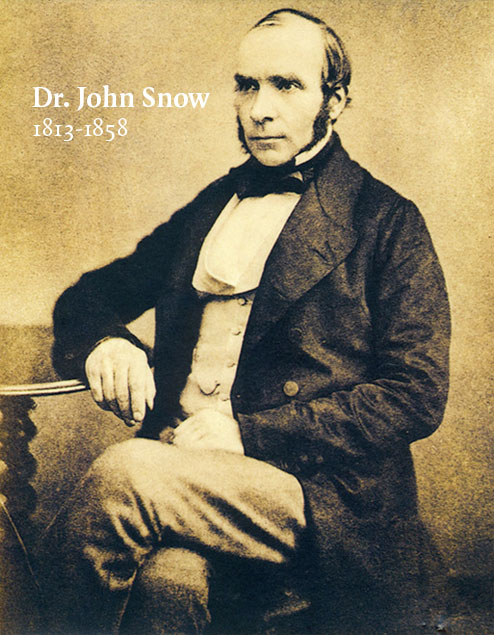

.jpg) deadliest documented foodborne illness outbreak in the United States was in the winter of 1924-1925, when typhoid in raw oysters from New York City killed approximately 150 people and sickened more than 1,500.

deadliest documented foodborne illness outbreak in the United States was in the winter of 1924-1925, when typhoid in raw oysters from New York City killed approximately 150 people and sickened more than 1,500.

Germany to homing in on the cause of cholera in the aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake.

Germany to homing in on the cause of cholera in the aftermath of Haiti’s earthquake. survey released in May and discussed by my friend and his wife as they drove to Vermont and back.

survey released in May and discussed by my friend and his wife as they drove to Vermont and back. “People would be horrified at the prospect of eating from a toilet seat however they ought to be aware that eating from a contaminated car dashboard may represent the same health hazards.”

“People would be horrified at the prospect of eating from a toilet seat however they ought to be aware that eating from a contaminated car dashboard may represent the same health hazards.” Lakers coach Phil Jackson said before Sunday’s game that Bryant would likely play despite being a little late to the game because of the illness.

Lakers coach Phil Jackson said before Sunday’s game that Bryant would likely play despite being a little late to the game because of the illness.  A spokesthing for Frontier Touring Company said,

A spokesthing for Frontier Touring Company said,.jpg) I didn’t feel hysterical with my own case of the green apple splatters over the weekend while sitting in the backseat with Sorenne, as Amy drove the five hours to Lebannon, Missouri, for a Thanksgiving dinner with her father and family. I spent the six hours we were there in the bed or bathroom, along with the five hour drive home, topped off with an, uh, uncomfortable night.

I didn’t feel hysterical with my own case of the green apple splatters over the weekend while sitting in the backseat with Sorenne, as Amy drove the five hours to Lebannon, Missouri, for a Thanksgiving dinner with her father and family. I spent the six hours we were there in the bed or bathroom, along with the five hour drive home, topped off with an, uh, uncomfortable night..jpg) That, according to would-be raw milk guru David Gumpert, would probably mean health types were being hysterical because they didn’t have better proof of causation.

That, according to would-be raw milk guru David Gumpert, would probably mean health types were being hysterical because they didn’t have better proof of causation. For every known case of foodborne illness, there are 10 -300 other cases, depending on the severity of the bug.?????? Most foodborne illness is never detected. It’s almost never the last meal someone ate or whatever other mythologies are out there. A stool sample linked with some epidemiology or food testing is required to make associations with specific foods.

For every known case of foodborne illness, there are 10 -300 other cases, depending on the severity of the bug.?????? Most foodborne illness is never detected. It’s almost never the last meal someone ate or whatever other mythologies are out there. A stool sample linked with some epidemiology or food testing is required to make associations with specific foods..jpg)

So here’s the abstract as a teaser.

So here’s the abstract as a teaser. The guidelines in this document are targeted to local, state and federal agencies and provide model practices used in foodborne disease outbreaks, including planning, detection, investigation, control and prevention. Local and state agencies vary in their approach to, experience with, and capacity to respond to foodborne disease outbreaks. The guidelines are intended to give all agencies a common foundation from which to work and to provide examples of the key activities that should occur during the response to outbreaks of foodborne disease. The guidelines were developed by a broad range of contributors from local, state and federal agencies with expertise in epidemiology, environmental health, laboratory science and communications. The document has gone through a public review and comment process.

The guidelines in this document are targeted to local, state and federal agencies and provide model practices used in foodborne disease outbreaks, including planning, detection, investigation, control and prevention. Local and state agencies vary in their approach to, experience with, and capacity to respond to foodborne disease outbreaks. The guidelines are intended to give all agencies a common foundation from which to work and to provide examples of the key activities that should occur during the response to outbreaks of foodborne disease. The guidelines were developed by a broad range of contributors from local, state and federal agencies with expertise in epidemiology, environmental health, laboratory science and communications. The document has gone through a public review and comment process.(4).jpg) In 2006, CDC reported 1,270 foodborne disease outbreaks (FBDOs) from all states and territories through the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System (FBDSS), resulting in 27,634 cases of foodborne illness and 11 deaths. Among the 624 FBDOs with a confirmed etiology, norovirus was the most common cause, accounting for 54% of outbreaks and 11,879 cases, followed by Salmonella (18% of outbreaks and 3,252 cases). Among the 11 reported deaths, 10 were attributed to bacterial etiologies (six Escherichia coli O157:H7, two Listeria monocytogenes, one Salmonella serotype Enteritidis, and one Clostridium botulinum), and one was attributed to a chemical (mushroom toxin).

In 2006, CDC reported 1,270 foodborne disease outbreaks (FBDOs) from all states and territories through the Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System (FBDSS), resulting in 27,634 cases of foodborne illness and 11 deaths. Among the 624 FBDOs with a confirmed etiology, norovirus was the most common cause, accounting for 54% of outbreaks and 11,879 cases, followed by Salmonella (18% of outbreaks and 3,252 cases). Among the 11 reported deaths, 10 were attributed to bacterial etiologies (six Escherichia coli O157:H7, two Listeria monocytogenes, one Salmonella serotype Enteritidis, and one Clostridium botulinum), and one was attributed to a chemical (mushroom toxin).