Sunday has become hockey day.

It’s winter in Brisbane, and the locals are wearing parkas and Uggs as daytime temperatures struggle to climb above 80F.

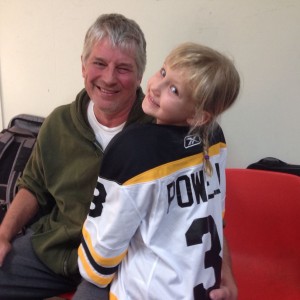

On Sunday June 25, I was getting ready to take 5-year-old daughter Sorenne to weekly hockey practice when I promptly barfed after breakfast.

On Sunday June 25, I was getting ready to take 5-year-old daughter Sorenne to weekly hockey practice when I promptly barfed after breakfast.

“But I’m the coach, I have to go.”

Amy the wife said, how can you preach that food workers shouldn’t show up to work sick when you won’t do it yourself?

She was right.

I stayed home.

The ice hockey world didn’t end (and I went and awesomely coached three hours of practice and games the next Sunday).

I realize the limitations when I, or the U.S Centers for Disease Control, tell the world, sick workers shouldn’t work. Economics and pride get in the way.

Liz Szabo writes in today’s USA Today that norovirus, the USA’s leading cause of foodborne illness, has become known as the “cruise ship virus” for causing mass outbreaks of food poisoning – and misery – on the high seas. Yet only about 1% of all reported norovirus outbreaks occur on cruise ships.

It might be more accurate to call it the “salad bar virus,” and not because customers are sneezing on the croutons.

But food handlers, such as cooks and waiters, cause about 70% of norovirus outbreaks related to contaminated food, mostly through touching “ready to eat” foods – such as sandwiches or raw fruit – with their bare hands, according to a new report from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 90% of contamination occurred during food preparation, and 75% of food involved in outbreaks was consumed raw.

Business practices in the food industry may contribute to the problem.

One in five restaurant workers admits having reported to work while sick with diarrhea and vomiting – the two main symptoms of norovirus – within the past year, the CDC says.

About 20 million Americans are sickened with norovirus every year, with a total of 48 million suffering food poisoning from all causes. The highly contagious family of viruses also causes up to 1.9 million doctor visits; 400,000 emergency room visits; up to 71,000 hospitalizations; and up to 800 deaths, mostly in young children or the elderly. Infections cost the country $777 million in health care costs.

Norovirus is wildly contagious.

Norovirus is wildly contagious.

As few as 18 viral particles can make people sick. In other words, a speck of viruses small enough to fit on the head of pin is potent enough to infect more than 1,000 people, according to the CDC report, released Tuesday. The virus can spread rapidly in close quarters, as well, such as dormitories, military barracks and nursing homes.

“Norovirus is one tough bug,” said CDC director Thomas Frieden.

Norovirus can make people violently ill so quickly that they don’t have time to reach a bathroom, says Doug Powell, a food safety expert in Brisbane, Australia, and author of barfblog.com. People who get sick in public often expose many others. Norovirus also can live on surfaces, such as countertops and serving utensils, for up to two weeks (I’m told it’s up to six weeks, which is why I always refer journalists to others more knowledgable about certain topics instead of talking out of my ass).

Norovirus is also the Terminator of germs — very tough to kill. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers don’t work very well, says Lee-Ann Jaykus, a professor of food science at North Carolina State University. That makes frequent handwashing important.

But even cooking may not kill noroviruses, which can survive the freezer and cooking temperatures above 140 degrees, the CDC says.

CDC recommends that restaurants offer paid sick leave and require food workers to stay home when sick, remaining out of work for at least 48 hours after symptoms cease. Restaurants should train their staffs well and have on-call workers who can fill in for sick co-workers. Lastly, restaurants should require food handlers to use disposable gloves and wash their hands frequently.

That may be easier said than done, says Powell, who notes that few restaurant workers today get paid sick leave. Many earn minimum wage and can’t afford to miss work. Others fear being fired if they call in sick.

Some restaurants are doing more than others, Jaykus says. “The large retailers are well-aware (of norovirus) and working very hard,” Jaykus says. “Smaller restaurants have, of course, fewer resources.”

The only good news about norovirus?

Scientists are working on a vaccine, although it’s in early stage.

And norovirus is less serious than other foodborne germs, such as salmonella, E. coli and listeria, all of which have led to recalls of fresh and frozen produce in recent years, Powell says. Although norovirus can sicken people for two to three days, it’s not usually fatal.

“You just feel like you’re dying,” Powell says.

The full CDC report is available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm63e0603a1.htm?s_cid=mm63e0603a1_e.

The March 24 Lion’s club meeting was held at the Nisswa Community Center, but was catered by Red, White and Blue Catering, which operates from the Nisswa American Legion.

The March 24 Lion’s club meeting was held at the Nisswa Community Center, but was catered by Red, White and Blue Catering, which operates from the Nisswa American Legion.