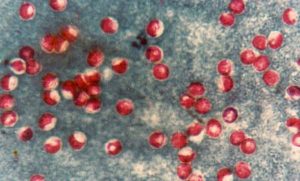

There has been an increase in reported outbreaks and cases of foodborne disease attributed to pathogenic Vibrio species. As a result, there have been several instances where the presence of pathogenic Vibrio spp. in seafood has led to a disruption in international trade.

The number of Vibrio species being recognized as potential human pathogens is increasing. The food safety concerns associated with these microorganisms have led to the need for microbiological risk assessment to support risk management decision making for their control.

The number of Vibrio species being recognized as potential human pathogens is increasing. The food safety concerns associated with these microorganisms have led to the need for microbiological risk assessment to support risk management decision making for their control.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is considered to be part of the autochthonous microflora in the estuarine and coastal environments in tropical to temperate zones. Food safety concerns have been particularly evident with V. parahaemolyticus. There have been a series of pandemic outbreaks of V. parahaemolyticus foodborne illnesses due to the consumption of seafood. In addition, outbreaks of V. parahaemolyticus have occurred in regions of the world where it was previously unreported. The vast majority of strains isolated from patients with clinical illness produce a thermostable direct haemolysin (TDH) encoded by the tdh gene. Clinical strains may also produce a TDH-related haemolysin (TRH) encoded by the trh gene. It has therefore been considered that those strains that possess the tdh and/or trh genes and produce TDH and/or TRH should be considered those most likely to be pathogenic. V. vulnificus can occasionally cause mild gastroenteritis in healthy individuals following consumption of raw bivalve molluscs. It can cause primary septicaemia in individuals with chronic pre-existing conditions, especially liver disease or alcoholism, diabetes, haemochromatosis and HIV/AIDS. This can be a serious, often fatal, disease with one of the highest fatality rates of any known foodborne bacterial pathogen.

The 41st Session of the Codex Committee on Food Hygiene (CCFH) requested FAO/WHO to convene an expert meeting to address a number of issues relating to V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus including:

- conduct validation of the predictive risk models developed by the United States of America based on FAO/WHO risk assessments, with a view to constructing more applicable models for wider use among member countries, including adjustments for strain virulence variations and ecological factors; xi

- review the available information on testing methodology and recommend microbiological methods for Vibrio spp. used to monitor the levels of pathogenic Vibrio spp. in seafood and/or water;

- conduct validation of growth rates and doubling times for V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus in Crassostrea virginica (Eastern or American oyster) using strains isolated from different parts of the world and different bivalve molluscan species.

The requested expert meeting was held on 13-17 September 2010, and this report is the outcome of this meeting. Rather than undertaking a validation exercise, the meeting considered it more appropriate to undertake an evaluation of the existing risk calculators with a view to determining the context to which they are applicable and potential modifications that would need to be made to extend their application beyond that context. A simplified calculator tool could then be developed to answer other specific questions routinely. This would be dependent on the availability of the appropriate data and effort must be directed towards this. The development of microbiological monitoring methods, particularly molecular methods for V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus is evolving rapidly. This means the identification of any single method for the purposes of monitoring these pathogens is challenging and also of limited value as the method is likely to be surpassed within a few years. Therefore, rather than making any single recommendation, the meeting considered it more appropriate to indicate a few of the monitoring options available while the final decision on the method selected will depend to a great extent on the specific purpose of the monitoring activity, the cost, the speed with which results are required and the technical capacity of the laboratory.

The requested expert meeting was held on 13-17 September 2010, and this report is the outcome of this meeting. Rather than undertaking a validation exercise, the meeting considered it more appropriate to undertake an evaluation of the existing risk calculators with a view to determining the context to which they are applicable and potential modifications that would need to be made to extend their application beyond that context. A simplified calculator tool could then be developed to answer other specific questions routinely. This would be dependent on the availability of the appropriate data and effort must be directed towards this. The development of microbiological monitoring methods, particularly molecular methods for V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus is evolving rapidly. This means the identification of any single method for the purposes of monitoring these pathogens is challenging and also of limited value as the method is likely to be surpassed within a few years. Therefore, rather than making any single recommendation, the meeting considered it more appropriate to indicate a few of the monitoring options available while the final decision on the method selected will depend to a great extent on the specific purpose of the monitoring activity, the cost, the speed with which results are required and the technical capacity of the laboratory.

The meeting considered that monitoring seawater for V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus in bivalve growth and harvest areas has limited value in terms of predicting the presence of these pathogens in bivalves. A linear relationship between levels of the vibrios in seawater and bivalves was not found and whatever relationship does exist can vary between region, the Vibrio spp. etc. Also, the levels of Vibrio species of concern in seawater tend to be very low. This presents a further challenge as the method used would need to have an appropriate level of sensitivity for their detection. Nevertheless, this does not preclude the testing of seawater for these vibrios; for example, in certain situations testing can provide an understanding of the aquatic microflora in growing areas. Monitoring of seafood for these pathogenic vibrios was considered the most appropriate way to get insight into the xii levels of the pathogens in these commodities at the time of harvest. Monitoring on an ongoing basis could be expensive, so consideration could be given to undertaking a study over the course of a year and using this as a means to establish a relationship between total and pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus in the seafood and abiotic factors such as water temperature and salinity. Once such a relationship is established for the harvest area of interest measuring these abiotic factors may be a more cost-effective way of monitoring.

The meeting undertook an evaluation exercise rather than attempting to validate the existing growth models. The experts considered the JEMRA growth model for V. vulnificus and the FDA growth model for V. parahaemolyticus were appropriate for estimating growth in the American oyster (Crassostrea virginica). The JEMRA growth model for V. vulnificus was appropriate for estimating growth in at least one other oyster species, Crassostrea ariakensis. The FDA model for V. parahaemolyticus was also appropriate for estimating growth in at least one other oyster species, Crassostrea gigas, but was not appropriate for predicting growth in the Sydney rock oyster (Saccostrea glomerata). There was some evidence that the V. parahaemolyticus models currently used over predict growth at higher temperatures (e.g. > 25 °C) in live oysters. This phenomenon requires further investigation. Growth model studies were primarily undertaken using natural populations of V. parahaemolyticus as these were considered to be the most representative. Data were limited and inconsistent with respect to the impact of the strain on growth rate although recent studies in live oysters suggest differences exist between populations possessing tdh/trh (pathogenic) versus total or non-pathogenic populations of V. parahaemolyticus.

There was no data to evaluate the performance of the growth models in any other oyster species or other filter feeding shellfish or other seafood and as such its use in these products could not be supported. If the models are used there should be a clear understanding of the associated uncertainty. This indicated a data gap which needs to be addressed before the risk assessments could be expanded in a meaningful manner.

Risk assessment tools for vibrio parahaemolyticus and vibrio vulnificus associated with seafood, 2020

FAO and WHO

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330867/9789240000186-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y