From a PhD dissertation by Jenni Luukkanen of the University of Helsinki. Here’s hoping the defence last week went well.

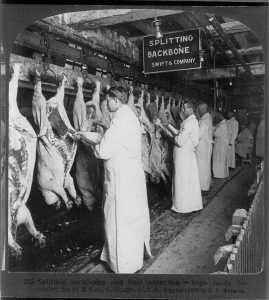

Official control in slaughterhouses, consisting of meat inspection and food safety inspection, has an important role in ensuring meat safety, animal health and welfare, and prevention of transmissible animal diseases. Meat inspection in the European Union (EU) includes the inspection of food chain information, live animals (ante-mortem inspection), and carcasses and offal (post-mortem inspection).

Official control in slaughterhouses, consisting of meat inspection and food safety inspection, has an important role in ensuring meat safety, animal health and welfare, and prevention of transmissible animal diseases. Meat inspection in the European Union (EU) includes the inspection of food chain information, live animals (ante-mortem inspection), and carcasses and offal (post-mortem inspection).

Food safety inspections are performed to verify slaughterhouses’ compliance with food safety legislation and are of the utmost importance, especially if slaughterhouses’ self-checking systems (SCSs) fail.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prerequisites for official control such as the functionality of the task distribution in meat inspection and certain meat inspection personnel-related factors. In addition, needs for improvement in slaughterhouses’ SCSs, meat inspection, and food safety inspections, including control measures used by the official veterinarians (OVs) and their efficacy, were examined. In the EU, competent authorities must ensure the quality of official control in slaughterhouses through internal or external audits, and the functionality of these audits was also studied.

Based on our results, meat inspection personnel (OVs and official auxiliaries [OAs]), slaughterhouse representatives, and officials in the central authority were mainly satisfied with the functionality of the present task distribution in meat inspection, although redistributing ante-mortem inspection from the OVs to the OAs was supported by some slaughterhouse representatives due to perceived economic benefit.

Ante-mortem inspection was assessed as the most important meat inspection task as a whole for meat safety, animal welfare, and prevention of transmissible animal diseases, and most of the respondents considered it important that the OVs perform antemortem inspection and whole-carcass condemnation in red meat slaughterhouses.

In a considerable number of slaughterhouses, OA or OV resources were not always sufficient and the lack of meat inspection personnel decreased the time used for food safety inspections according to the OVs, also affecting some of the red meat OAs’ post-mortem inspection tasks. The frequency with which OVs observed post-mortem inspection performed by the OAs varied markedly in red meat slaughterhouses. In addition, roughly one-third of the red meat OAs did not consider the guidance and support from the OVs to be adequate in post-mortem inspection.

According to our results, the most common non-compliance in slaughterhouses concerned hygiene such as cleanliness of premises and equipment, hygienic working methods, and maintenance of surfaces and equipment. Chief OVs in a few smaller slaughterhouses reported more frequent and severe non-compliances than other slaughterhouses, and in these slaughterhouses the usage of written time limits and enforcement measures by the OVs was more infrequent than in other slaughterhouses.

According to our results, the most common non-compliance in slaughterhouses concerned hygiene such as cleanliness of premises and equipment, hygienic working methods, and maintenance of surfaces and equipment. Chief OVs in a few smaller slaughterhouses reported more frequent and severe non-compliances than other slaughterhouses, and in these slaughterhouses the usage of written time limits and enforcement measures by the OVs was more infrequent than in other slaughterhouses.

Deficiencies in documentation of food safety inspections and in systematic follow-up of corrections of slaughterhouses’ non-compliance had been observed in a considerable number of slaughterhouses. In meat inspection, deficiencies in inspection of the gastrointestinal tract and adjacent lymph nodes were most common and observed in numerous red meat slaughterhouses. Internal audits performed to evaluate the official control in slaughterhouses were considered necessary, and they induced correction of observed non-conformities. However, a majority of the interviewed OVs considered that the meat inspection should be more thoroughly audited, including differences in the rejections and their reasons between OAs. Auditors, for their part, raised a need for improved follow-up of the audits.

Our results do not give any strong incentive to redistribute meat inspection tasks between OVs, OAs, and slaughterhouse employees, although especially from the red meat slaughterhouse representatives’ point of view the cost efficiency ought to be improved. Sufficient meat inspection resources should be safeguarded in all slaughterhouses, and meat inspection personnel’s guidance and support must be emphasized when developing official control in slaughterhouses. OVs ought to focus on performing follow-up inspections of correction of slaughterhouses’ non-compliance systematically, and also the documentation of the food safety inspections should be developed.

Hygiene in slaughterhouses should receive more attention; especially in slaughterhouses with frequent and severe non-compliance, OVs should re-evaluate and intensify their enforcement.

Hygiene in slaughterhouses should receive more attention; especially in slaughterhouses with frequent and severe non-compliance, OVs should re-evaluate and intensify their enforcement.

The results attest to the importance of internal audits in slaughterhouses, but they could be developed by including auditing of the rejections and their underlying reasons and uniformity in meat inspection.

in 2016. The questionnaire study also aimed to recognize factors affecting compliance and disagreements about gradings with a special focus on FBOs’ risk perception. In total 1277 responses from FBOs in retail (n=523), service (n=507) and industry (n=247) sectors revealed that the majority of FBOs perceived the disclosure to promote correction of non-compliance. However, many FBOs disagreed with the grading of inspection findings.

in 2016. The questionnaire study also aimed to recognize factors affecting compliance and disagreements about gradings with a special focus on FBOs’ risk perception. In total 1277 responses from FBOs in retail (n=523), service (n=507) and industry (n=247) sectors revealed that the majority of FBOs perceived the disclosure to promote correction of non-compliance. However, many FBOs disagreed with the grading of inspection findings.