The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is collaborating with provincial public health partners, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and Health Canada to investigate an outbreak of Salmonella infections involving Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. The outbreak appears to be ongoing, as recent illnesses continue to be reported to PHAC.

Based on the investigation findings to date, exposure to eggs has been identified as a likely source of the outbreak. Many of the individuals who became sick reported consuming, preparing, cooking and baking at home with eggs. Some individuals reported exposure to eggs at an institution (including nursing homes and hospitals) where they resided or worked before becoming ill.

Based on the investigation findings to date, exposure to eggs has been identified as a likely source of the outbreak. Many of the individuals who became sick reported consuming, preparing, cooking and baking at home with eggs. Some individuals reported exposure to eggs at an institution (including nursing homes and hospitals) where they resided or worked before becoming ill.

Eggs can sometimes be contaminated with Salmonella bacteria on the shell and inside the egg. The bacteria are most often transmitted to people when they improperly handle, eat or cook contaminated foods.

Illnesses can be prevented if proper safe food handing and cooking practices are followed. PHAC is not advising consumers to avoid eating properly cooked eggs, but this outbreak serves as a reminder that Canadians should always handle raw eggs carefully and cook eggs and egg-based foods to an internal temperature of at least 74 C (165 F) to ensure they are safe to eat.

PHAC is issuing this public health notice to inform Canadians of the investigation findings to date and to share important safe food handling practices to help prevent further Salmonella infections.

As the outbreak investigation is ongoing, it is possible that additional sources could be identified, and food recall warnings related to this outbreak may be issued. This public health notice will be updated as the investigation evolves.

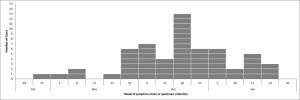

As of February 18, 2021, there have been 57 laboratory-confirmed cases of Salmonella Enteritidis illness investigated in the following provinces: Newfoundland and Labrador (25), and Nova Scotia (32). Individuals became sick between late October 2020 and late January 2021. Nineteen individuals have been hospitalized. No deaths have been reported. Individuals who became ill are between 2 and 98 years of age. The majority of cases (68%) are female.

As of February 18, 2021, there have been 57 laboratory-confirmed cases of Salmonella Enteritidis illness investigated in the following provinces: Newfoundland and Labrador (25), and Nova Scotia (32). Individuals became sick between late October 2020 and late January 2021. Nineteen individuals have been hospitalized. No deaths have been reported. Individuals who became ill are between 2 and 98 years of age. The majority of cases (68%) are female.

Between October and December 2020, CFIA issued food recall warnings for a variety of eggs distributed in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador. The recalled eggs are now past their shelf-life and are no longer available for purchase. Some individuals who became sick in this outbreak reported exposure to recalled eggs; however, there are a number of recent ill individuals that do not.

It is possible that more recent illnesses may be reported in the outbreak because there is a period of time between when a person becomes ill and when the illness is reported to public health officials. For this outbreak, the illness reporting period is between three and six weeks.

Anyone can become sick with a Salmonella infection, but young children, the elderly, pregnant women or people with weakened immune systems are at higher risk for contracting serious illness.

Most people who become ill from a Salmonella infection will recover fully after a few days. It is possible for some people to be infected with the bacteria and to not get sick or show any symptoms, but to still be able to spread the infection to others.

Raw or undercooked eggs and egg-based foods carrying Salmonella may look, smell and taste normal, so it’s important to always follow safe food-handling tips if you are buying, cleaning, chilling, cooking and storing any type of eggs or egg-based foods. If contaminated, the Salmonella may be found on the shell itself or may be inside the egg. The following food preparation tips may help reduce your risk of getting sick, but they may not fully eliminate the risk of illness.

- Always handle raw eggs carefully and cook eggs and egg-based foods to an internal temperature of at least 74°C (165°F) to ensure they are safe to eat.

- Do not eat raw or undercooked eggs. Cook eggs until both the yolk and white are firm.

- When purchasing eggs, choose only refrigerated eggs with clean, uncracked shells.

- Always wash your hands before and after you touch raw eggs. Wash with soap and warm water for at least 20 seconds. Use an alcohol-based hand rub if soap and water are not available.

- Eggs (whether raw or cooked) should not be kept at room temperature for more than two hours. Eggs that have been at room temperature for more than two hours should be thrown out.

- Use pasteurized egg products instead of raw eggs when preparing foods that aren’t heated (such as icing, eggnog or Caesar salad dressing).

- Do not taste raw dough, batter or any other product containing raw eggs. Eating even a small amount could make you sick.

- Microwave cooking of raw eggs is not recommended because of the possibility of uneven heating.

- Sanitize countertops, cutting boards and utensils before and after preparing eggs or egg-based foods. Use a kitchen sanitizer (following the directions on the container) or a bleach solution (5 mL household bleach to 750 mL of water), and rinse with water.

- Do not re-use plates, cutting boards or utensils that have come in contact with raw eggs unless they have been thoroughly washed, rinsed and sanitized.

- Use paper towels to wipe kitchen surfaces, or change dishcloths daily to avoid the risk of cross-contamination and the spread of bacteria. Avoid using sponges as they are harder to keep bacteria-free.

- Do not prepare food for other people if you think you are sick with a Salmonella infection or suffering from any other contagious illness causing diarrhea.

Symptoms of a Salmonella infection, called salmonellosis, typically start 6 to 72 hours after exposure to Salmonella bacteria from an infected animal or contaminated product.

Symptoms include:

- fever

- chills

- diarrhea

- abdominal cramps

- headache

- nausea

- vomiting

These symptoms usually last for 4 to 7 days. In healthy people, salmonellosis often clears up without treatment, but sometimes antibiotics may be required. In some cases, severe illness may occur and hospitalization may be required. People who are infected with Salmonella bacteria can be infectious from several days to several weeks. People who experience symptoms, or who have underlying medical conditions, should contact their health care provider if they suspect they have a Salmonella infection.

These symptoms usually last for 4 to 7 days. In healthy people, salmonellosis often clears up without treatment, but sometimes antibiotics may be required. In some cases, severe illness may occur and hospitalization may be required. People who are infected with Salmonella bacteria can be infectious from several days to several weeks. People who experience symptoms, or who have underlying medical conditions, should contact their health care provider if they suspect they have a Salmonella infection.

The Public Health Agency of Canada leads the human health investigation into an outbreak and is in regular contact with its federal, provincial and territorial partners to monitor the situation and to collaborate on steps to address an outbreak.

Health Canada provides food-related health risk assessments to determine whether the presence of a certain substance or microorganism poses a health risk to consumers.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency conducts food safety investigations into the possible food source of an outbreak.