The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concludes that raw milk can carry harmful bacteria that can cause serious illness. Implementing current good hygiene practices at farms is essential to reduce raw milk contamination, while maintaining the cold chain is also important to prevent or slow the growth of bacteria in raw milk. However, these practices alone do not eliminate these risks. Boiling raw milk before consumption is the best way to kill many of the bacteria that can make people sick.

Consumer interest in drinking raw milk has been growing in the European Union (EU) as many people believe it has health benefits. Under EU hygiene rules, Member States can prohibit or restrict the placing on the market of raw milk intended for human consumption. Sale of raw drinking milk through vending machines is permitted in some Member States, but consumers are usually instructed to boil the milk before consumption.

Consumer interest in drinking raw milk has been growing in the European Union (EU) as many people believe it has health benefits. Under EU hygiene rules, Member States can prohibit or restrict the placing on the market of raw milk intended for human consumption. Sale of raw drinking milk through vending machines is permitted in some Member States, but consumers are usually instructed to boil the milk before consumption.

In their scientific opinion on public health risks associated with raw milk in the EU, experts from EFSA’s Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ) conclude that raw milk can be a source of harmful bacteria – mainly Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC).

The Panel could not quantify the public health risks associated with drinking raw milk in the EU due to data gaps. However, according to Member State data on food-borne disease outbreaks, between 2007 and 2013, 27 outbreaks were due to the consumption of raw milk.

Most of them – 21 – were caused by Campylobacter, one was caused by Salmonella, two by STEC and three by tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). A large majority of the outbreaks were due to raw cow’s milk, while a few of them originated from raw goat’s milk.

“There is a need for improved communication to consumers on the hazards and control measures associated with consumption of raw drinking milk,” says John Griffin, Chair of the BIOHAZ Panel.

Infants, children, pregnant women, old people and those with a weakened immune system have a higher risk of falling ill from drinking raw milk.

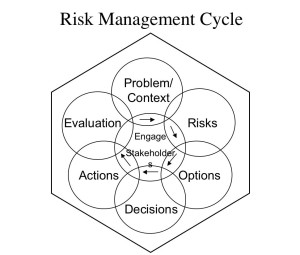

Raw drinking milk (RDM) has a diverse microbial flora which can include pathogens transmissible to humans. The main microbiological hazards associated with RDM from cows, sheep and goats, horses and donkeys and camels were identified using a decision tree approach.

This considered evidence of milk-borne infection and the hazard being present in the European Union (EU), the impact of the hazard on human health and whether there was evidence for RDM as an important risk factor in the EU.

This considered evidence of milk-borne infection and the hazard being present in the European Union (EU), the impact of the hazard on human health and whether there was evidence for RDM as an important risk factor in the EU.

The main hazards were Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Brucella melitensis, Mycobacterium bovis and tick-borne encephalitis virus, and there are clear links between drinking raw milk and human illness associated with these hazards.

A quantitative microbiological risk assessment for these hazards could not be undertaken because country and EU-wide data are limited. Antimicrobial resistance has been reported in several EU countries in some of the main bacterial hazards isolated from raw milk or associated equipment and may be significant for public health. Sale of RDM through vending machines is permitted in some EU countries, although consumers purchasing such milk are usually instructed to boil the milk before consumption, which would eliminate microbiological risks. With respect to internet sales of RDM, there is a need for microbiological, temperature and storage time data to assess the impact of this distribution route. Intrinsic contamination of RDM with pathogens can arise from animals with systemic infection as well as from localised infections such as mastitis.

Extrinsic contamination can arise from faecal contamination and from the wider farm environment. It was not possible to rank control options as no single step could be identified which would significantly reduce risk relative to a baseline of expected good practice, although potential for an increase in risk was also noted. Improved risk communication to consumers is recommended.

Extrinsic contamination can arise from faecal contamination and from the wider farm environment. It was not possible to rank control options as no single step could be identified which would significantly reduce risk relative to a baseline of expected good practice, although potential for an increase in risk was also noted. Improved risk communication to consumers is recommended.

Summary

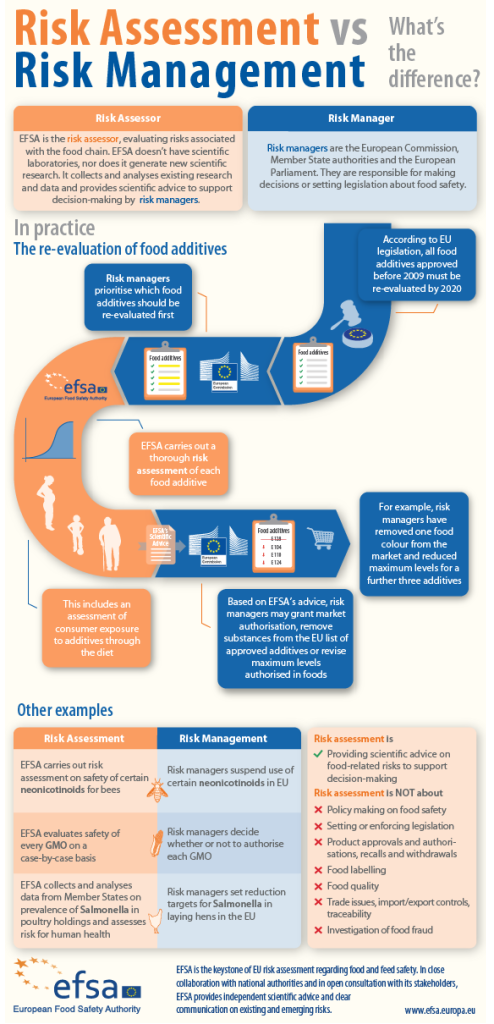

Following a request from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ) was asked to deliver a scientific opinion on the public health risks related to the consumption of raw drinking milk (RDM). In particular, the BIOHAZ Panel was requested to identify the main microbiological hazards of public health significance that may occur in RDM from different animal species, to assess the public health risk arising from the consumption of RDM, to assess the likelihood of RDM being a significant source of antimicrobial resistant bacteria/resistance genes, to assess the additional risks associated with the sale of RDM through vending machines and via the internet and to identify and rank potential control options to reduce public health risks arising from consumption of RDM.

According to European Union (EU) legislation, “raw milk” is defined as milk produced by the secretion of the mammary gland of farmed animals that has not been heated to more than 40 °C or undergone any treatment that has an equivalent effect (Regulation (EC) No 853/2004). A top-down four-step decision tree was used to identify the main microbiological hazards associated with RDM of different milk-producing species in the EU. Microbiological hazards that can be transmitted to humans through milk and which were reported from cows, sheep and goats, horses and donkeys and camels in the EU were listed. Those hazards which could be transmitted via milk but were not reported from milk-producing animals in the EU were excluded from further consideration. Microbiological hazards identified as potentially transmissible through milk and present in the EU milk-producing animal population included the bacteria Campylobacter spp. (thermophilic), Salmonella spp., shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Bacillus cereus, Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, Listeria monocytogenes, Mycobacterium bovis, Staphylococcus aureus, Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Corynebacterium spp., Streptococcus suis subsp. zooepidemicus,the parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptosporidium parvum and the virus tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). Those hazards transmissible via milk of one species and present in the EU were also considered to be potentially transmissible by milk of other species if present in the EU.

Evidence for RDM as an important risk factor for human infection in the EU was based on epidemiological evidence that the hazard has been associated with illness from the consumption of RDM in the EU, the extent of occurrence of the hazard in different milk-producing species in the EU, the prevalence of the hazard in milk bulk tanks or retail RDM in the EU, and expert opinion. Between 2007 and 2012 there were 27 reported outbreaks in the EU involving RDM. Of these, 21 were attributed to Campylobacter spp., predominantly C. jejuni, one to Salmonella Typhimurium, two to STEC and three to TBEV. Four of the 27 outbreaks were due to raw milk from goats, the rest being attributed to raw milk from cows. The published literature was also considered, which highlighted additional outbreaks of TBEV and outbreaks of B. melitensis, M. bovis and STEC, although some of these were prior to 2007. No outbreaks attributable to L. monocytogenes in RDM were reported between 2007 and 2012.

Evidence for RDM as an important risk factor for human infection in the EU was based on epidemiological evidence that the hazard has been associated with illness from the consumption of RDM in the EU, the extent of occurrence of the hazard in different milk-producing species in the EU, the prevalence of the hazard in milk bulk tanks or retail RDM in the EU, and expert opinion. Between 2007 and 2012 there were 27 reported outbreaks in the EU involving RDM. Of these, 21 were attributed to Campylobacter spp., predominantly C. jejuni, one to Salmonella Typhimurium, two to STEC and three to TBEV. Four of the 27 outbreaks were due to raw milk from goats, the rest being attributed to raw milk from cows. The published literature was also considered, which highlighted additional outbreaks of TBEV and outbreaks of B. melitensis, M. bovis and STEC, although some of these were prior to 2007. No outbreaks attributable to L. monocytogenes in RDM were reported between 2007 and 2012.

STEC, Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. are essentially ubiquitous pathogens and are likely to be found in milk-producing animals and their milk throughout the EU, as indicated by prevalence data from raw milk testing. TBEV was also considered to be a main hazard based on outbreak data, together with evidence of spread in Europe and the virus being detected in raw milk. B. melitensis and M. bovis have been associated with outbreaks involving raw milk, but these are less common and more geographically restricted than the other pathogens and control programmes in Europe have generally been successful in reducing human disease from these pathogens.

For other hazards, epidemiological evidence of illness was either historical or limited to reports from outside Europe. L. monocytogenes infection is associated with a high mortality rate in vulnerable groups, and the organism was as frequent as Campylobacter and STEC in raw milk. The lack of robust epidemiological data (including outbreaks) linking listeriosis to consumption of raw milk in Europe meant that it could not be considered a main hazard. The ability of L. monocytogenes to grow at chill temperatures, coupled with its prevalence in raw milk, suggests that further study in relation to RDM may be justified, particularly as several risk assessment models outside Europe have already been developed for this pathogen.

There is a clear link between drinking raw milk and human illness with Campylobacter spp., S. Typhimurium, STEC, TBEV, B. melitensis and M. bovis, with the potential for severe health consequences in some individual patients. Owing to the lack of epidemiological data, the burden of disease linked to the consumption of raw milk could not be assessed. Published quantitative microbiological risk assessment (QMRA) models from Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Italy, for Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., STEC O157 and L. monocytogenes in RDM from cows, were reviewed to identify their strengths and limitations. No QMRAs were available for RDM of other species. The risk estimates provided by the QMRA models reviewed cannot be extrapolated to the European situation as a whole. The outputs from the Australian and New Zealand risk assessments for STEC O157 and Salmonella spp. estimate a high level of milk contamination, which contrasts with the outputs from the risk assessment for these pathogens in RDM in one region of northern Italy, where the risk associated with STEC O157 was estimated as very low because of model uncertainty. Similarly, the Australian and New Zealand risk assessments predicted a higher risk for Campylobacter spp. than the risk assessment conducted in one region of northern Italy, largely as a result of differences in the extent of faecal contamination. From the model used in the Australian study it can be concluded that improving on-farm hygiene leads to a decrease in the number of predicted cases of illness due to Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp. and STEC O157 from the consumption of RDM. A QMRA could have helped in further estimating the public health risks and evaluating the effect of the mitigation options in Europe for these hazards, but could not be undertaken because country and EU-wide data are limited.

There is a clear link between drinking raw milk and human illness with Campylobacter spp., S. Typhimurium, STEC, TBEV, B. melitensis and M. bovis, with the potential for severe health consequences in some individual patients. Owing to the lack of epidemiological data, the burden of disease linked to the consumption of raw milk could not be assessed. Published quantitative microbiological risk assessment (QMRA) models from Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Italy, for Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., STEC O157 and L. monocytogenes in RDM from cows, were reviewed to identify their strengths and limitations. No QMRAs were available for RDM of other species. The risk estimates provided by the QMRA models reviewed cannot be extrapolated to the European situation as a whole. The outputs from the Australian and New Zealand risk assessments for STEC O157 and Salmonella spp. estimate a high level of milk contamination, which contrasts with the outputs from the risk assessment for these pathogens in RDM in one region of northern Italy, where the risk associated with STEC O157 was estimated as very low because of model uncertainty. Similarly, the Australian and New Zealand risk assessments predicted a higher risk for Campylobacter spp. than the risk assessment conducted in one region of northern Italy, largely as a result of differences in the extent of faecal contamination. From the model used in the Australian study it can be concluded that improving on-farm hygiene leads to a decrease in the number of predicted cases of illness due to Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp. and STEC O157 from the consumption of RDM. A QMRA could have helped in further estimating the public health risks and evaluating the effect of the mitigation options in Europe for these hazards, but could not be undertaken because country and EU-wide data are limited.

Antimicrobial resistance has been reported in several EU countries in isolates of Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., STEC and S. aureus from raw milk or associated equipment such as milk filters, and may be significant for public health. Such isolates have been primarily associated with raw milk from bovine animals, which may reflect the more limited screening of milk from other species. Strains of Campylobacter spp., and particularly C. jejuni, exhibiting resistance predominantly to tetracyclines but also to some other antimicrobials have been reported in two Member States (MS). There have been no reports of antimicrobial resistance in isolates of Salmonella spp. from outbreaks associated with raw/unpasteurised in the EU in countries other than the UK. In the USA, there has been a report of a raw milk-associated outbreak caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. Typhimurium, with a single fatality ascribed to resistance of the organism to antibiotics. Despite STEC O157 being the organism most commonly associated with RDM-related outbreaks of STEC gastrointestinal illness in several EU countries, little information is available about the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in such outbreak strains. Antimicrobial resistance has been reported in a water buffalo raw milk-associated STEC O26 outbreak in one MS in 2008 and in raw milk-associated STEC outbreaks in the USA. Antimicrobial resistance in isolates of L. monocytogenes from raw milk and raw milk dairy products has only rarely been reported in EU countries.

Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has not been isolated during outbreaks of infection associated with RDM in EU countries. Although not typically regarded as a food-borne pathogen, there have been increasing reports of the isolation of MRSA from dairy farms and bulk tank milk in several EU MS. Although identified in E. coli in bovine animals in some MS, extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL)/AmpC gene-carrying bacteria have not been reported in RDM in EU MS. In the USA, a range of Salmonella serovars with ESBL/AmpC genes have been identified in raw milk surveys.

Sale of RDM through vending machines is permitted in some EU MS, with considerable variation in the number of machines in different countries. There is little indication of RDM other than cow’s milk being sold through vending machines. Although vending machines dispense drinking milk in a raw state, consumers are usually instructed to boil the milk prior to consumption. If consumers were to comply with these instructions, the microbiological risks associated with raw milk would be eliminated. The temperature of RDM in vending machines is generally kept below 4 °C and therefore variability in milk temperature is more likely to arise between the farm and vending machine and between the vending machine and point of consumption by the consumer. One study in Italy demonstrated that temperature variability in the supply chain from farm to consumer could potentially result in the multiplication of L. monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium and STECO157:H7.

Fresh and frozen RDM of different species (cows, goats, sheep and camels) is available via internet sales although there are no data on the microbiological or temperature controls for these milks from the bulk milk tank through to the point of consumption. The variability in temperature control and duration of storage by consumers would contribute to the multiplication of some pathogens if these are present in the milk.

The steps in the production to consumption chain for RDM present many opportunities for contamination by microorganisms, some of which may be transmissible to humans. Intrinsic contamination of milk can arise from systemic infection in the milk-producing animal as well as from localised infections, such as mastitis. Extrinsic contamination of milk can arise from faecal contamination and from the wider farm environment associated with collection and storage of milk. Observance of good animal health and husbandry, together with the application of good agricultural practices (GAPs) and good hygienic practices (GHPs), are essential to minimise opportunities for contamination of RDM with pathogens in the production to consumption chain for RDM. No single step could be identified which would provide a significant reduction in risk relative to a baseline of expected good animal health and welfare and good agricultural and hygienic practices. Therefore, it was not possible to rank control options with respect to risk reduction since any deviations from the expected “best practice” baseline are likely to result in an increase in risk.

The reviewed QMRA models identified on-farm hygiene control and maintenance of the cold chain as factors influencing the outcome of the models for some pathogens. Although L. monocytogenes is not considered to be one of the main hazards associated with RDM in the EU, the reviewed QMRAs from outside the EU do show that the risk associated with L. monocytogenes in raw cow’s milk can be mitigated and reduced significantly if the cold chain is well controlled, the shelf-life of raw milk is limited to a few days and there is consumer compliance with these measures/controls.

The BIOHAZ Panel identified several recommendations arising from the opinion. There is a need for a better evidence base to inform future prioritisation and ranking approaches and studies should be undertaken to systematically collect data for source attribution for the hazards identified as associated with RDM and collect data to identify and rank emerging milk-borne hazards. Because of the diverse range of potential microbiological hazards associated with different milk-producing animals, hazard identification should be revisited regularly. There is a need for validated growth and survival models for pathogens in RDM of different milk-producing species, particularly in relation to the temperature and storage time of RDM from the producer up to the point of consumption. Finally, the Panel recommended that there should be improved risk communication to consumers, particularly susceptible/high risk populations, regarding the hazards and control methods associated with consumption of RDM.

.jpeg) outbreak in sprouts last year that killed 53 and sickened 4,400.

outbreak in sprouts last year that killed 53 and sickened 4,400..jpg) consumer exposure as well as the public health impact of control measures.

consumer exposure as well as the public health impact of control measures.