In the words of WKRP sales legend Herb Tarlek, tacky sells.

So does disgust.

(A reason it’s called barblog?)

(A reason it’s called barblog?)

In North Carolina, there’s a company that manufactures bottles of an artificial fart spray called Liquid Ass™. The makers (who call themselves Assman #1 and Assman #2) are clearly proud of their product, writing lyrically on their website of its “genuine, foul butt-crack smell with hints of dead animal and fresh poo”.

The site also features user testimonials, mostly along the lines of “I sprayed this stuff all over a friend’s car, then laughed myself silly as he tried to work out where the stench came from”.

What the website fails to mention, however, is the vital role these little bottles of nastiness are playing in the cutting-edge experiments conducted, in perfect seriousness, by Auckland University psychology researchers.

Over the past few years, a team has been luring experimental subjects into a small room on the 12th floor of a building in Auckland City Hospital, putting them into a state of mild disgust with a covertly deployed dose of Liquid Ass (which, despite the stench, is non-toxic), then running a battery of psychological tests.

Other adventures facing the subjects included being handed a bag that looked like it may once have contained excrement.

It’s tempting to think that this proves little more than the popular hypothesis that psychologists are sadistic weirdos, but in fact these experiments are yielding powerful  insights into the nature of human emotions.

insights into the nature of human emotions.

More practically, they are providing clues for how to deal with some of the most intractable problems facing modern healthcare.

The man behind these experiments is Associate Professor Dr Nathan Consedine, director of the health psychology programme in the Department of Psychological Medicine.

He’s 42, has a skinny moustache vaguely reminiscent of Salvador Dali’s, and has been studying emotions and their role in healthcare throughout a career that began in Christchurch and has included long stints at Columbia University and Long Island University in New York.

It was only in 2009, though, after returning to New Zealand, that Consedine started paying close attention to the significance of one emotion in particular: disgust. It is, says Consedine, the “elephant in the room” when it comes to healthcare.

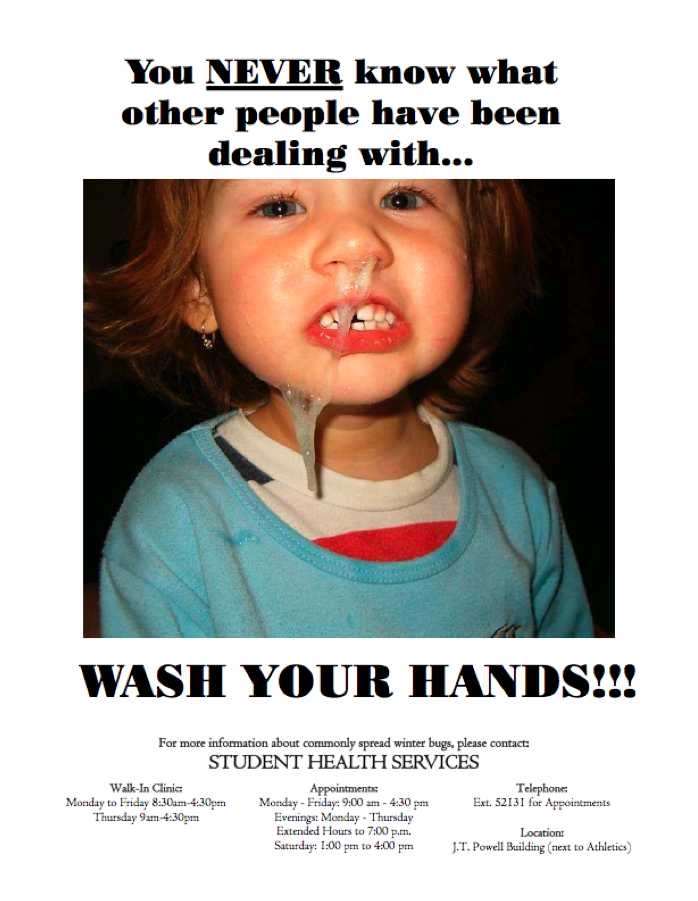

far less effective than ads that also "disgust" consumers into taking the action. The best way to elicit disgust: Display totally gross images (see our

far less effective than ads that also "disgust" consumers into taking the action. The best way to elicit disgust: Display totally gross images (see our  ad with the same written copy, but which replaced the photo of the pock-marked young man with one of a coffin.

ad with the same written copy, but which replaced the photo of the pock-marked young man with one of a coffin. when disgust was far from the mainstream.

when disgust was far from the mainstream. because they often present dangers to public health.

because they often present dangers to public health.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans. better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today.

better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today.