Why is meat inspected?

Why does it have to be overseen by veterinarians?

.jpg) Does inspection result in fewer sick people?

Does inspection result in fewer sick people?

Do inspectors have pathogen-seeking goggles?

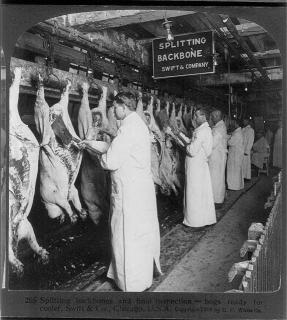

The Washington Post reports this morning that every day, inspectors in white hats and coats take up positions at every one of the nation’s slaughterhouses, eyeballing the hanging carcasses of cows and chickens as they shuttle past on elevated rails, looking for bruises, tumors and signs of contamination.

It’s essentially the way U.S. Department of Agriculture food safety inspectors have done their jobs for a century.

But why? Today’s meat inspection seems grounded in repetition and historical precedent rather than science.

In 1184, city leaders in Toulouse, France, introduced some of the first documented measures to oversee the sale of meat: profit for butchers was limited to eight per cent; the partnership between two butchers was forbidden; and, selling the meat of sick animals was forbidden unless the buyer was warned.??By 1394, the Toulouse charter on butchering contained 60 articles, 19 of which were devoted to health and safety.?

As outlined by Madeleine Ferrières, a professor of social history at the University of Avignon, in her 2002 book, Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, the goal of regulations at butcher shops — the forerunners of today’s slaughterhouse — was to safeguard consumers and increase tax revenues.

Primarily increase tax revenues.

Animals from the surrounding countryside were consolidated at a single spot — the evolving slaughterhouse, originally inside city walls — so taxes could be more easily gathered, and so animals could be physically examined for signs of disease.??It’s no different today: slaughterhouses are common collection points to examine animals for signs of disease and to collect various levies.

Bernard Vallat, Director General of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), said a couple of years ago that veterinary legislation is the foundation of any efficient animal health policy.

??”Veterinary legislation is a critical infrastructure element for all countries. In many OIE Member countries, the veterinary legislation has not been updated for many years and is obsolete or inadequate in structure and content for the challenges facing veterinary services in today’s world. Dr Vallat said that it is important that the veterinary services have the authority to enter livestock premises and other establishments and take the actions needed for early detection, reporting and rapid and effective management of any animal diseases as soon as they are detected. Such actions include the capacity to seize animals and products, to impose standstills, quarantine, testing and .jpg) other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”

other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”

That’s an attempt to answer the why-inspect-meat question, but it won’t be found in the Post story.

The Post story does explain that in some large slaughterhouses, USDA inspectors must regularly shave slices off the surface of different pieces of meat and send them to labs to test for E. coli.

But science has done little to thin the ranks of traditional inspectors. The law requires that they be present whenever animals are slaughtered and that they visit meat processing plants at least once a day. The USDA has more than 7,500 people doing the job.

The USDA launched an initiative in 1997 that would have shifted some responsibility for identifying carcass defects on slaughter lines to food company employees so that inspectors could focus more on microbial contaminations, USDA officials said. But a year later, the American Federation of Government Employees, some federal inspectors and a public-interest group sued to block the plan, alleging that it scrapped the carcass-by-carcass inspections required by the 1906 law.

As a result of the court battle, the USDA was forced to keep at least one inspector on each slaughter line.

Richard Raymond, a former USDA undersecretary of food safety, tried another approach in 2005. He worked to reallocate the time inspectors spend in meat processing plants based on the facilities’ safety record and the risk posed by the foods processed: Ground-beef plants, for example, would get more attention than a canned-ham operation.

But after two years of discussion with the food industry, consumer groups and unions, Congress barred the USDA from using funds to pursue the initiative. Raymond said he suspects that unions, fearful for their members’ jobs, blocked the effort.

In Canada, the years following the 2008 listeria-in-Maple-Leaf-deli-meat outbreak that killed 23, the federal inspectors’ union has had the public discussion volume set to shrill.

Canadian union president Bob Kingston said in the past few days (months, years) that any cuts to Canadian Food Inspection Agency inspector staffing would “be devastating.”

.jpg) He doesn’t say why.

He doesn’t say why.

Would more federal government inspectors have prevented the Maple Leaf mess? No. Do Canadian inspectors possess Superman-style listeria detection goggles? No. Do more inspectors make food safer? No.

In January, the USDA unveiled a proposal that would keep one inspector on each poultry slaughter line while the rest focused on what the agency considers higher risks, such as testing poultry for pathogens. Much of the responsibility for spotting obvious problems with the carcasses would fall to the plant’s employees.

The voluntary proposal would save taxpayers more than $90 million over three years, lower production costs for the industry by $257 million a year and better protect the public against contaminants, USDA officials say.

But these days, the bulk of what Americans eat — seafood, vegetables, fruit, dairy products, shelled eggs and almost everything except meat and poultry — is regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. And the FDA inspects the plants it oversees on average about once a decade.

These radically different approaches are a legacy from a time when animal products were thought to be inherently risky and other food products safe. But in the past few years, the high-profile and deadly outbreaks of foodborne illness linked to spinach, peanuts and cantaloupe have put the lie to that assumption.

The FDA’s approach is partly by necessity: The agency lacks the money to marshal more inspectors.

But it also reflects a different philosophy about how to address threats to the nation’s food supply: an approach based on where the risk is greatest.

“We have two extremes in the inspection programs,” said Michael Doyle, a nationally known microbiologist who directs the Center for Food Safety at the University of Georgia. “Neither system is working very well. They both need to be updated and upgraded.”

At the USDA, tight federal budgets and scientific advances over the past century make the case for new ways to manage risk, one that relies less on basic observation by an army of inspectors. But bureaucratic politics and union power have blunted these initiatives.

“I’m sure the resources can be allocated better,” said Michael Batz, a University of Florida researcher who studied the risks posed by different foods. “But each agency has a mandate. USDA, because of its mandate, has very little discretion about how it can use its resources. FDA has a broader mission, but, I think it’s fair to say, not enough resources.”

Regardless of whether local, state or federal, inspection are present to hold producers accountable, as part of a tax collection scheme, or to make food safer, the best slaughterhouses, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond the minimal standards of government.

And stop whining about it.

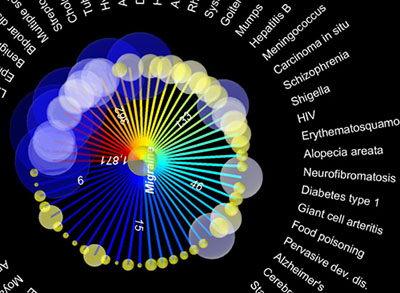

Because none of this chatter among the, err, chatting classes means fewer people are barfing from the food they consume.

Technology Networks reports the healthy human oral microbiome consists of not just clean teeth and firm gums, but also energy-efficient bacteria living in an environment rich in blood vessels that enables the organisms’ constant communication with immune-system cells and proteins.

Technology Networks reports the healthy human oral microbiome consists of not just clean teeth and firm gums, but also energy-efficient bacteria living in an environment rich in blood vessels that enables the organisms’ constant communication with immune-system cells and proteins.

.jpg) Does inspection result in fewer sick people?

Does inspection result in fewer sick people?.jpg) other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”

other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.”.jpg) He doesn’t say why.

He doesn’t say why. accurate data, but timely data."

accurate data, but timely data." agree that it is great for one thing: communication.

agree that it is great for one thing: communication. importing sausages from Germany to continue a meal tradition started by the actress’s mother.

importing sausages from Germany to continue a meal tradition started by the actress’s mother.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans. better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today.

better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today. Department on Thursday.

Department on Thursday.