My friend Tim Caufield, professor of law at the University of Alberta, the Research Director of its Health Law Institute, and current Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy, writes in an op-ed for the Globe and Mail that COVID public health policies have been with us for a year. So has uncertainty. We’ve all lived through twelve months of “huh”? And this has added to the public’s frustration, fatigue, and stress.

In the early weeks and months of the pandemic, there was uncertainty about masks and asymptomatic spread. There was uncertainty about if and when we’d get a vaccine. There was uncertainty about what type of public health policies worked best and were most needed. We have all had to tolerate a lot of ambiguity. And as the vaccines roll out, we are being asked to tolerate even more. (When will I get a vaccine? Which one will I get? And what about the variants?)

In the early weeks and months of the pandemic, there was uncertainty about masks and asymptomatic spread. There was uncertainty about if and when we’d get a vaccine. There was uncertainty about what type of public health policies worked best and were most needed. We have all had to tolerate a lot of ambiguity. And as the vaccines roll out, we are being asked to tolerate even more. (When will I get a vaccine? Which one will I get? And what about the variants?)

For public health communications to be effective, the public must have confidence in the message. And, unfortunately, for some, that confidence isn’t there. A recent study from the University of Calgary explored pandemic communication and found, not surprisingly, that “participants felt that public health messaging to date has been conflicting and at times unclear.”

This perception is understandable. An atmosphere of seemingly relentless uncertainty and confusion has been created by a combination of scientific realities, media practices, some less-than-ideal communication from policy makers, and the spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

The science surrounding COVID was – and, for some topics, continues to be – highly uncertain. While a growing body of evidence has emerged around the most contested issues (such as the value of masks and physical distancing strategies), early in the pandemic there wasn’t much that was unequivocal. The science evolved and, as you would hope with any evidence-informed approach, the resulting science advice and recommendations evolved too. But for some, shifting policies, even if appropriate, just added to a sense, rightly or not, of chaos.

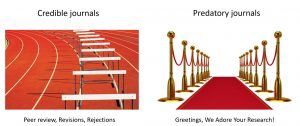

In addition, the media has been reporting on the research as it unfolds, including referencing studies that have not yet been peer reviewed. Often the preliminary or uncertain nature of the relevant research is not reported in the media, thus creating a false impression about the actual state of the science – as exemplified by the “hydroxychloroquine works!” debacle (PS, it doesn’t). Perhaps worse, relatively fringe perspectives – such as those pushing the value of “natural herd immunity” – have been given a relatively high profile in both the conventional press and on social media. This can create a false balance (fringe idea vs. broad scientific consensus) that we know can be detrimental to both public discourse and health behaviours.

In addition, the media has been reporting on the research as it unfolds, including referencing studies that have not yet been peer reviewed. Often the preliminary or uncertain nature of the relevant research is not reported in the media, thus creating a false impression about the actual state of the science – as exemplified by the “hydroxychloroquine works!” debacle (PS, it doesn’t). Perhaps worse, relatively fringe perspectives – such as those pushing the value of “natural herd immunity” – have been given a relatively high profile in both the conventional press and on social media. This can create a false balance (fringe idea vs. broad scientific consensus) that we know can be detrimental to both public discourse and health behaviours.

Despite the frustration that uncertainty can create, the public has a demonstrated preference for honesty about the limits of our knowledge. A recent study from Germany found that “a majority of respondents indicated a preference for open communication of scientific uncertainty in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.” This finding agrees with other research that has found that when uncertainty is relevant to their lives, the public wants to know about it.

People may want to hear about uncertainty, but will communicating it do more harm than good? Will it just add to an already confused information environment? The data on this point are actually fairly mixed, but recent research exploring the impact of communicating scientific uncertainty found that it either increased perceptions of trust in science or had almost no impact. This is good news. As the authors of one of the studies notes, “this should allow academics and science communicators to be more transparent about the limits of human knowledge.” Other studies have found that being honest about uncertainties in media reports about research can actually boost the perceived credibility of journalists.

And over the long term, honesty about the uncertainties of the evidence used to inform policy seems essential to the maintenance of public trust. For example, being overly dogmatic about a policy or predictive model could hurt the credibility of decision makers if new evidence requires a revision of a past positions.

When possible, public health authorities (or anyone seeking to communicate science) should start with well-defined and well-supported takeaway messages (e.g., please get vaccinated with whatever vaccine is available to and recommended for you!).But then be honest about what is not known (e.g., while vaccines are our best defense, we aren’t sure how long immunity will last).

Depending on the medium used (a social media post, for example, may not be the best venue for a long discourse on methodological challenges), it may also be wise to explain the limits of the research approach (e.g., observational studies can’t prove causation). If there are areas of scientific disagreement, be honest about that too – but be specific about what is being disputed. Often there is broad agreement about the big stuff (e.g., vaccines work!), but academic debate about some details. Often those trying to sow doubt – like those in the anti-vaccine community – will try to weaponize and over-emphasize small academic disagreements. Don’t give them that room.

When communicating about uncertainty it is also important to highlight what is being done to reduce it, such as forthcoming research or new data analysis. This provides a road map forward and invites the public to follow the science as it unfolds. It is also a way to stress that uncertainty is a natural part of the scientific process.

When communicating about uncertainty it is also important to highlight what is being done to reduce it, such as forthcoming research or new data analysis. This provides a road map forward and invites the public to follow the science as it unfolds. It is also a way to stress that uncertainty is a natural part of the scientific process.

For the public, try not to let the uncertainty kerfuffle distract you from the big picture. Remember that there are many clear knowns. Vaccines, physical distancing, hand washing, masks, and being responsible when symptoms emerge will get us through this pandemic.

Finally, it is also important to take a break from all the uncertainty noise. Studies have shown that the constant consumption of conflicting COVID news can (no surprise here) add to our stress. Put down the phone, back away from the screen, and take ten from “huh?”