The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports:

- Since July 3, 2015, 285 people infected with the outbreak strains of Salmonella Poona have been reported from 27 states.

- 53 ill people have been hospitalized, and one death has been reported from California.

54% of ill people are children younger than 18 years.

54% of ill people are children younger than 18 years.- Epidemiologic, laboratory, and traceback investigations have identified imported cucumbers from Mexico and distributed by Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce as a likely source of the infections in this outbreak.

- 58 (73%) of 80 people interviewed reported eating cucumbers in the week before their illness began.

- Eleven illness clusters have been identified in seven states. In all of these clusters, interviews found that cucumbers were a food item eaten in common by ill people.

- The San Diego County Health and Human Services Agency isolated Salmonella from cucumbers collected during a visit to the Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce facility.

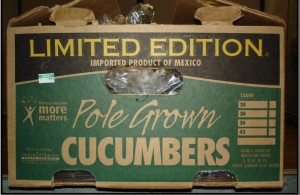

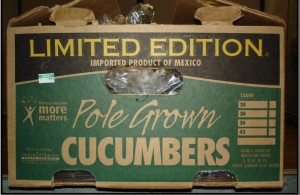

- On September 4, 2015, Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce voluntarily recalled all cucumbers sold under the “Limited Edition” brand label during the period from August 1, 2015 through September 3, 2015 because they may be contaminated with Salmonella.

- The type of cucumber is often referred to as a “slicer” or “American” cucumber and is dark green in color. Typical length is 7 to 10 inches.

- Limited Edition cucumbers were distributed in the states of Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah. Further distribution to other states may have occurred.

- Consumers should not eat, restaurants should not serve, and retailers should not sell recalled cucumbers.

- If you aren’t sure if your cucumbers were recalled, ask the place of purchase or your supplier. When in doubt, don’t eat, sell, or serve them and throw them out.

- CDC’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System laboratory is conducting antibiotic resistance testing on clinical isolates collected from ill people infected with the outbreak strains; results will be reported when they become available.

- This investigation is ongoing. CDC will provide updates when more information is available.

CDC, multiple states, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are investigating a multistate outbreak of Salmonella Poona infections linked to imported cucumbers from Mexico and distributed by Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce.

Public health investigators are using the PulseNet system to identify illnesses that may be part of this outbreak. PulseNet, the national subtyping network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories, is coordinated by CDC. DNA “fingerprinting” is performed on Salmonella bacteria isolated from ill people by using a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE. PulseNet manages a national database of these DNA “fingerprints” to identify possible outbreaks. Three DNA “fingerprints” (outbreak strains) are included in this investigation.

Public health investigators are using the PulseNet system to identify illnesses that may be part of this outbreak. PulseNet, the national subtyping network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories, is coordinated by CDC. DNA “fingerprinting” is performed on Salmonella bacteria isolated from ill people by using a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE. PulseNet manages a national database of these DNA “fingerprints” to identify possible outbreaks. Three DNA “fingerprints” (outbreak strains) are included in this investigation.

As of September 3, 2015, 285 people infected with the outbreak strains of Salmonella Poona have been reported from 27 states. The number of ill people reported from each state is as follows: Alaska (8), Arizona (60), Arkansas (6), California (51), Colorado (14), Idaho (8), Illinois (5), Kansas (1), Louisiana (3), Minnesota (12), Missouri (7), Montana (11), Nebraska (2), Nevada (7), New Mexico (15), New York (4), North Dakota (1), Ohio (2), Oklahoma (5), Oregon (3), South Carolina (6), Texas (9), Utah (30), Virginia (1), Washington (9), Wisconsin (2), and Wyoming (3).

Among people for whom information is available, illnesses started on dates ranging from July 3, 2015 to August 26, 2015. Ill people range in age from less than 1 year to 99, with a median age of 13. Fifty-four percent of ill people are children younger than 18 years. Fifty-seven percent of ill people are female. Among 160 people with available information, 53 (33%) report being hospitalized. One death has been reported from California.

On September 4, 2015, Andrew & Williamson Fresh Produce voluntarily recalled all cucumbers sold under the “Limited Edition” brand label during the period from August 1, 2015 through September 3, 2015 because they may be contaminated with Salmonella. The type of cucumber is often referred to as a “slicer” or “American” cucumber. It is dark green in color and typical length is 7 to 10 inches. In retail locations it is typically sold in a bulk display without any individual packaging or plastic wrapping. Limited Edition cucumbers were distributed in the states of Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah and reached customers through retail, food service companies, wholesalers, and brokers. Further distribution to other states may have occurred.

Sorta easy to do in North America at the end of summer.

Sorta easy to do in North America at the end of summer.

(1).jpg) cucumber?

cucumber?.jpg) tested; all were negative for microsporidia. A retrospective cohort study identified 135 case-patients (attack rate 30%). The median incubation period was 9 days.

tested; all were negative for microsporidia. A retrospective cohort study identified 135 case-patients (attack rate 30%). The median incubation period was 9 days. .jpg) Saxony-Anhalt said.

Saxony-Anhalt said.