Some people publish in peer-reviewed journals; some publish reports; some publish for a vanity press.

According to a report from the U.S. Center for Science in the Public Interest, outbreak data show that Americans are twice as likely to get food poisoning from food prepared at a restaurant than food prepared at home.

Except that outbreaks from a restaurant — where many people could be exposed to risk — are much more likely to get reported.

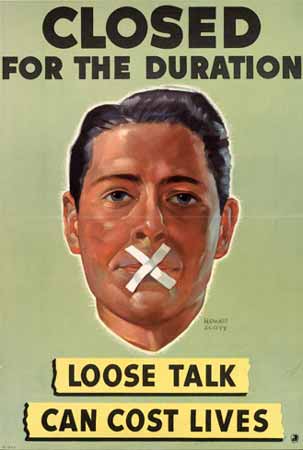

I don’t know where most outbreaks happen, but I do know there are a lot of people and groups that make bullshit statements.

I don’t know where most outbreaks happen, but I do know there are a lot of people and groups that make bullshit statements.

It’s OK to say, I don’t know. Especially when followed with, this is what I’m doing to find out more. And when I find out more, you’ll hear if from me first.

And yes, one could argue that it matters where foodborne illness happens to more efficiently allocate preventative resources, but we’re not even close to that in terms of meaningful data collection.

C.J. Jacob and D.A. Powell. 2009. Where does foodborne illness happen—in the home, at foodservice, or elsewhere—and does it matter? Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. November 2009, 6(9): 1121-1123

Foodservice professionals, politicians, and the media are often cited making claims as to which locations most often expose consumers to foodborne pathogens. Many times, it is implied that most foodborne illnesses originate from food consumed where dishes are prepared to order, such as restaurants or in private homes. The manner in which the question is posed and answered frequently reveals a speculative bias that either favors homemade or foodservice meals as the most common source of foodborne pathogens. Many answers have little or no scientific grounding, while others use data compiled by passive surveillance systems. Current surveillance systems focus on the place where food is consumed rather than the point where food is contaminated. Rather than focusing on the location of consumption—and blaming consumers and others—analysis of the steps leading to foodborne illness should center on the causes of contamination in a complex farm-to-fork food safety system.

Nothing?

Nothing? The story is soft on spinach and leafy green producers – why did it take 29 outbreaks before industry took microbial food safety issues seriously – and appropriately harsh on the Ponzi scheme of food safety audits.

The story is soft on spinach and leafy green producers – why did it take 29 outbreaks before industry took microbial food safety issues seriously – and appropriately harsh on the Ponzi scheme of food safety audits.

“Her mother decided that there was no room in the fridge, so she did the next best thing, throwing the turkey into the swimming pool to thaw. It wasn’t heated, so the water was in the low 60s. The good news is that we convinced mom to rescue the bird from the pool. The bad news — we did not get a picture of the floating turkey.”

“Her mother decided that there was no room in the fridge, so she did the next best thing, throwing the turkey into the swimming pool to thaw. It wasn’t heated, so the water was in the low 60s. The good news is that we convinced mom to rescue the bird from the pool. The bad news — we did not get a picture of the floating turkey.” Here’s Steve in action with some visiting Russian team. As Chapman correctly notes, this photo perfectly exhibits Naylor:

Here’s Steve in action with some visiting Russian team. As Chapman correctly notes, this photo perfectly exhibits Naylor: Much is being made this morning about a new report from the

Much is being made this morning about a new report from the