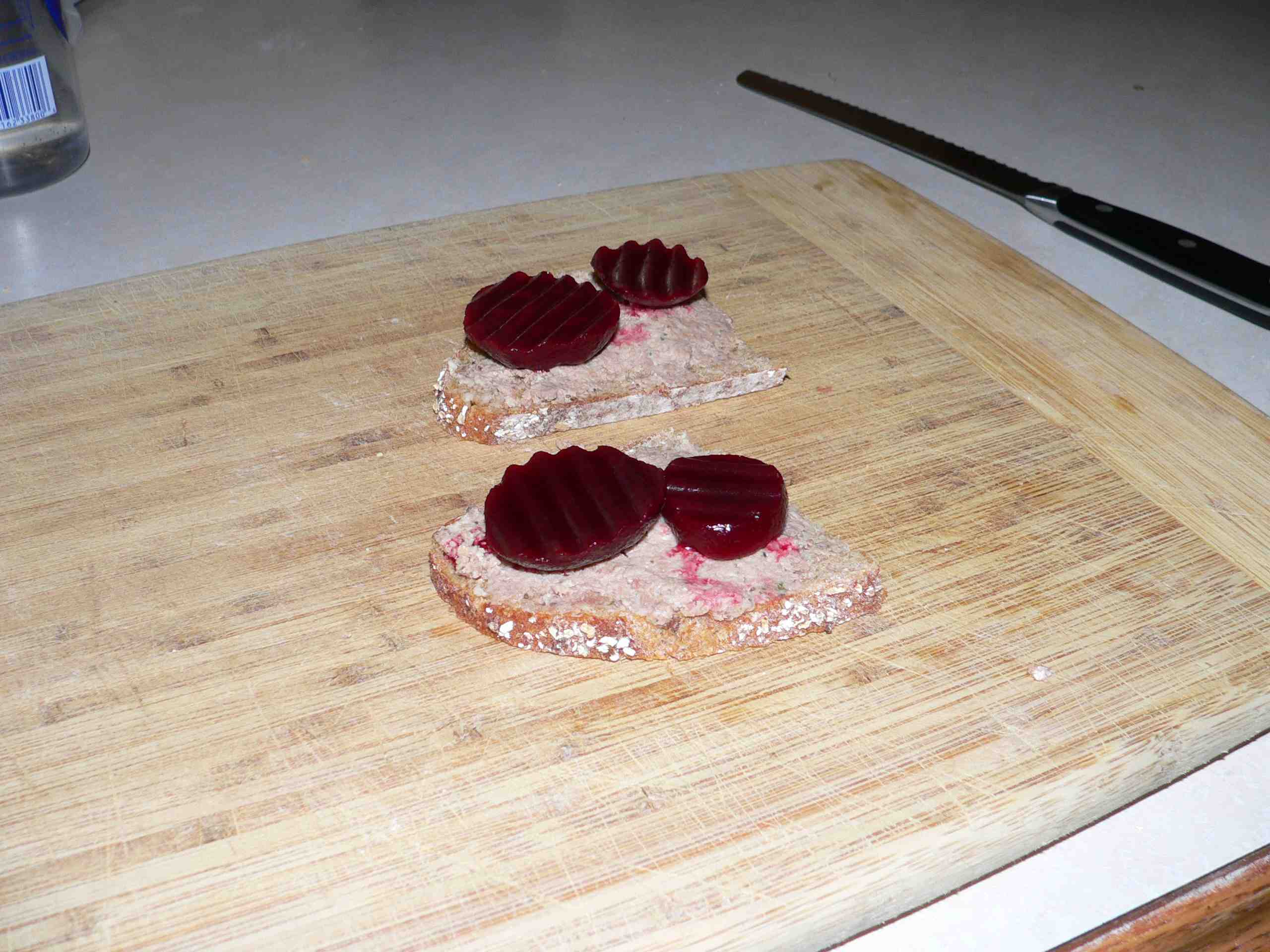

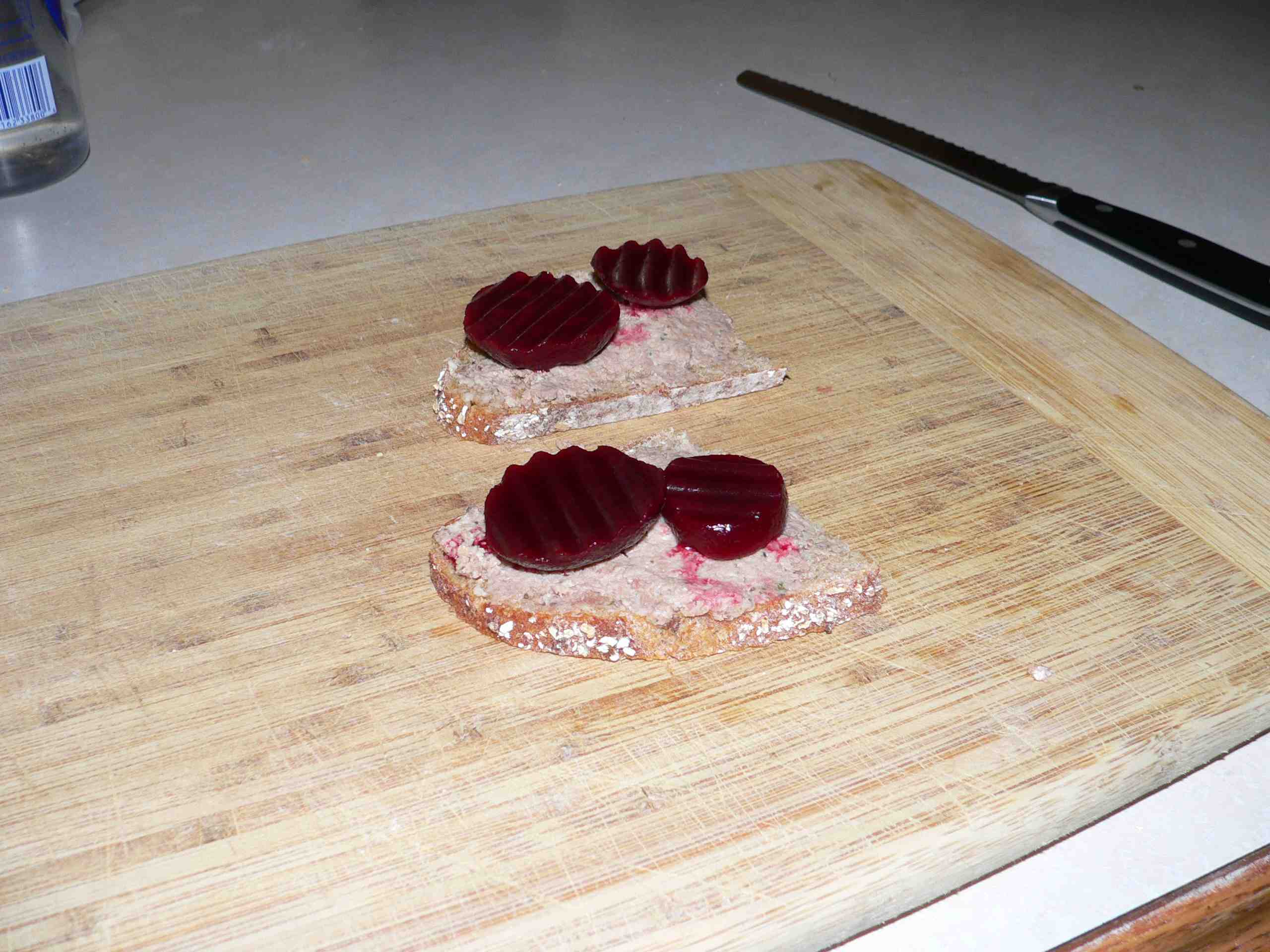

I spent five summers in high school and university hammering nails and planks with a couple of Danish craftsmen. They taught me many things, including how to eat pate and beet sandwiches (lunch today, right), along with raw herring and vast quantities of aquavit.

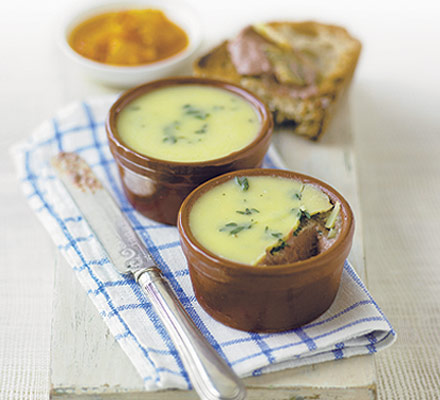

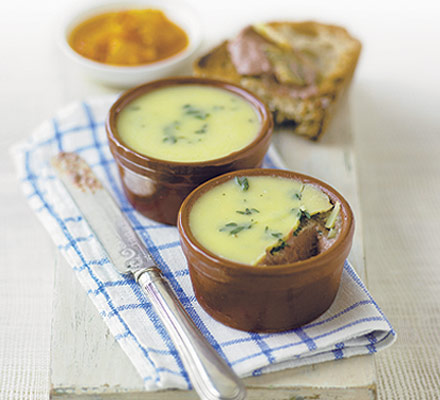

Eurosurveillance reports this week on an outbreak of campylobacter associated with chicken liver parfait served in Scotland in June. Undercooking appears to be the  culprit, probably because the cooks went with ‘piping hot’ rather than a thermometer. One web site says a chicken liver pate becomes a chicken liver parfait (French for perfect) when the cooked liver mixture is pushed through a sieve to remove any sinewy bits, resulting in a silkier, smoother and luscious liver parfait.

culprit, probably because the cooks went with ‘piping hot’ rather than a thermometer. One web site says a chicken liver pate becomes a chicken liver parfait (French for perfect) when the cooked liver mixture is pushed through a sieve to remove any sinewy bits, resulting in a silkier, smoother and luscious liver parfait.

It’s on the Internet so it must be true. The full report follows.

In an outbreak of 24 cases of gastroenteritis among guests at a wedding reception, 13 cases had confirmed Campylobacter infection. In a cohort study, univariate analysis revealed a strong association with consumption of chicken liver parfait: risk ratio (RR): 30.08, 95% confidence interval (CI): 4.34-208.44, p<0.001, which remained after adjustment for potential confounders in a multivariable model: RR=27.8, 95% CI=3.9-199.7, p=0.001. These analyses strongly support the hypothesis that this outbreak was caused by the consumption of chicken liver parfait.

Background

Campylobacteriosis is an acute bacterial enteric disease, caused by infection with Campylobacter. Common symptoms include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, malaise, fever, nausea, and/or vomiting [1] and may persist for a week or even longer [2]. Onset is usually between two and five days after exposure, but may be up to 10 days. The infectious dose required to cause Campylobacter illness is estimated to be as low as 500 organisms [3]. Campylobacter infection continues to be the most commonly reported cause of foodborne illness in England and Wales, with 57,772 laboratory reports of Campylobacter cases received by the Health Protection Agency (HPA) in 2009 [4].

Despite the high incidence of this disease, the HPA received only 114 reports of foodborne Campylobacter outbreaks between 1992 and 2009, of which 25 (22%) were recorded as being linked to consumption of poultry liver dishes [5]. Chicken liver foods carry a high risk of Campylobacter infection as the bacteria can infect both the external and internal tissue of chicken livers [6], and may remain in chicken liver if insufficiently cooked [7]. The association between poultry liver dishes and outbreaks of Campylobacter infection has been illustrated by two recently published studies from Scotland [8,9].

On 5 July 2010, a suspected outbreak of campylobacteriosis was reported to the North East Health Protection Unit (HPU) by Environmental Health Officers from Northumberland County Council. Reports of illness were received from guests at a wedding held at a luxury hotel in Northumberland on 25 June 2010. One guest was hospitalised with Campylobacter infection following the event. In total, 13 guests who ate at the event submitted samples that tested positive for Campylobacter. The event consisted of a wedding breakfast (afternoon meal) and an evening buffet.

At the first Outbreak Control Team meeting on 7 July 2010, the decision was made to undertake an analytical study. Reports of illness were only received from guests who had attended the wedding breakfast, and accordingly the study was carried out on this group.

Method

Study design and cohort?

A retrospective cohort study was used. The cohort was defined as persons who had eaten the wedding breakfast at the luxury hotel on 25 June 2010 (n=67). Contact details for these 67 guests were obtained from the event organiser. The evening buffet was excluded because no cases were reported in guests attending only the evening buffet. All reported cases attended the wedding breakfast (three of them attended only the wedding breakfast).

Data collection

Of the 67 guests listed by the event organiser, 65 were posted a questionnaire with a covering letter and a stamped and addressed return envelope. The remaining two guests, resident outside the United Kingdom (UK), were sent an electronic copy of the covering letter and questionnaire via email in order to maintain the timeliness of  the investigation. One week after the first posting, a follow-up letter was sent to those guests whose questionnaires were still to be received.

the investigation. One week after the first posting, a follow-up letter was sent to those guests whose questionnaires were still to be received.

Case definition

Cases were defined as persons who attended the wedding at the hotel on 25 June 2010, who reported an illness with diarrhoea or vomiting, with or without other gastrointestinal symptoms, and with an onset of illness between 26 June 2010 and 5 July 2010. Guests with illness onset dates less than one day or greater than 10 days after the event were included as non-cases.

Response rate?

Of the 67 persons on the guest list, two were found to be infants who did not eat the wedding breakfast and were excluded from the study, giving a potential cohort size of 65. Completed questionnaires were received from 60 of 65 remaining guests (92%).

Questionnaire content?

The questionnaire contained questions regarding personal details, illness information, travel history, other illness in the household, food and drink consumed at the meal, in addition to other questions relating to the participant’s stay at the hotel. The menu for the wedding breakfast was obtained from the hotel; details from this menu were used to inform the content of the questionnaire.

Statistical analyses?

Data were double-entered using EpiData v3.1 (EpiData Association) and then verified and analysed using STATA 10.1 (StataCorp). The association between exposure variables and illness was examined using univariate, stratified methods (using Mantel-Haenszel risk ratios and the Woolf test for homogeneity) and multivariable methods (logistic and binary regression).

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

Of the 60 individuals included in the study, 24 fitted the case definition. Of these 24, 13 received laboratory confirmation of Campylobacter infection. Illness onset dates for cases ranged from 26 to 30 June 2010 (Figure 1). The incubation period ranged from one to five days (mean = 2.25 days). The symptoms experienced by cases are shown in Table 1; duration of symptoms ranged from 1 to 18 days. A mean duration of symptoms cannot be calculated as 13 of 24 cases were still experiencing symptoms when answering the questionnaire.

Analytical epidemiology

In a univariate analysis, the strength of association between the risk of becoming a case and 40 exposures was calculated. Of these, four exposures were significantly (p<0.05) associated with illness; these are shown in Table 2. From this univariate analysis, chicken liver parfait was the variable most strongly associated with illness, with a risk ratio (RR) of 30.08.

Of variables significantly associated with illness, chicken liver parfait, onion marmalade and the mixed leaf salad were served in the same set dish. Whilst cheesecake is positively associated with illness, it only explains 14 of the 24 cases, whereas chicken liver parfait explains 23 of the 24 cases.

To examine potential confounding and effect modification between variables, significant exposures (p<0.05) were stratified for exposure to chicken liver parfait and Mantel-Haenszel RRs calculated (Table 3). Consumption of chicken liver parfait strongly confounded each of these variables, and after stratification the association between these exposures and illness was no longer significant.

Multivariable analysis was conducted using logistic and binary regression models. The four variables significantly associated with illness in the univariate analysis were included in an initial logistic regression model. Variables were then removed in a stepwise fashion, in the order of the univariate p value, and a likelihood ratio (LR) test was conducted. As these models did not have significantly different log likelihoods (LR test p<0.05), the original model was used.

As the results of the multivariable model show (Table 4), when adjusting for other significant exposures, chicken liver parfait (RR= 27.8, 95% CI: 3.9-199.7) remained significantly associated with illness.

Microbiology

Due to the time between the event and notification of the outbreak (10 days), no samples of food from the wedding remained for microbiological analysis. However, environmental samples from the kitchen were taken. Based on results from these environmental samples, the general hygiene of the premises was determined to be satisfactory.

Discussion

These results show a very strong association between consumption of chicken liver parfait at the wedding breakfast and Campylobacter illness. The multivariable analysis of food items demonstrates that even after adjusting for confounding variables, guests who ate chicken liver parfait had a risk of illness that was 28 times greater than guests who did not eat this food.

An investigation by Environmental Health Officers identified concerns about the method used to prepare the chicken liver parfait for this event. Information from the hotel indicates that after mixing raw chicken livers with a red wine reduction and raw eggs, the parfait mixture was heated, using a bain marie (water bath), to a core temperature of 65°C and then immediately removed from the oven and cooled for 15 minutes. According to the UK Food Standards Agency advice, if liver is cooked at 65°C, it should be held at this temperature for at least ten minutes to ensure adequate cooking [10].

One of the most positive elements in the implementation of this study was the high response rate (92%) to the postal questionnaire. This may have been due to factors such as the prompt posting of the questionnaire after the wedding, the type of event concerned and the high proportion of guests reporting illness.

Other factors, such as the relatively short length of questionnaire, the inclusion of a personalised letter, first class postage, the inclusion of a stamped and addressed return envelope, and follow up contact of non-respondents, have all been previously associated with increasing response rates to postal questionnaires [11].

It is possible that the study was affected by an ascertainment bias, in that the suggestion that chicken liver parfait had caused the outbreak may have circulated among guests, biasing their responses in the questionnaire. However, the number of portions recorded as having been eaten in the questionnaires was similar to the hotel’s estimate of portions served, suggesting that the effect of this bias was inconsequential. Also, the case definition was such that guests reporting diarrhoea or vomiting, independent of other symptoms, were included as cases. This may have led to the misclassification of non-cases as cases, reducing the strength of observed associations.

The outbreak investigation was conducted in a timely fashion, which minimised recall bias in questionnaire responses and enabled prompt implementation of control measures. As a result of this outbreak investigation, the hotel, one of a group of six, reviewed their catering operations, removing certain high risk foods from their menus and implementing quarterly unannounced kitchen inspections.

Of the 25 foodborne Campylobacter outbreaks linked to chicken liver parfait/pâté reported to the HPA between 1992 and 2009, 17 were recorded to have been due to errors in food handling during preparation of the chicken liver dishes. These food handling errors included inadequate cooking of blended livers in a bain marie [5].

From 2007 to 2009, the proportion of foodborne Campylobacter outbreaks in England and Wales that were linked with chicken liver dishes increased significantly [12], indicating that the consumption of this food is a public health issue of escalating importance.

From the evidence available, it is likely that the cooking method used for the chicken liver parfait was insufficient to ensure that the food was free from Campylobacter bacteria. These findings demonstrate the importance of influencing catering practice with regard to the cooking of chicken livers, to reduce the risk of campylobacteriosis outbreaks.

References

Heymann DL, editor. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 19th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2008: 94-8.

Butzler JP, Oosterom J. Campylobacter: pathogenicity and significance in foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12(1):1-8.

Robinson DA. Infective dose of Campylobacter jejuni in milk. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282(6276):1584.

Health Protection Agency (HPA). Campylobacter infections per year in England and Wales, 1989-2009. London:HPA; [Accessed 1 Nov 2010]. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/Campylobacter/EpidemiologicalData/campyDataEw/

Little CL, Gormley FJ, Rawal N, Richardson JF. A recipe for disaster: Outbreaks of campylobacteriosis associated with poultry liver pâté in England and Wales. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(12):1691-4.

Baumgartner A, Grand M, Lininger M, Simmen A. Campylobacter contaminations of poultry liver – consequences for food handlers and consumers. Archiv Lebensmittelhyg. 1995;46:1-24

Whyte R, Hudson JA, Graham C. Campylobacter in chicken livers and their destruction by pan frying. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43(6):591-5.

O’Leary MC, Harding O, Fisher L, Cowden J. A continuous common-source outbreak of campylobacteriosis associated with changes to the preparation of chicken liver pâté. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(3):383-8.

Forbes KJ, Gormley FJ, Dallas JF, Labovitiadi O, MacRae M, Owen RJ, et al. Campylobacter Immunity and Coinfection following a Large Outbreak in a Farming Community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(1):111-16.

Food Standards Agency (FSA). Caterers warned on chicken livers. London:FSA. Accessed 28 Jul 2010. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2010/jul/livers

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;324(7347):1183.

Health Protection Agency (HPA). Food-borne outbreaks of Campylobacter (associated with poultry liver dishes) in England. Health Protection Report. 3(49); 11 Dec 2009. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2009/news4909.htm

.jpg) District, said the problem in a nutshell was one of being unfamiliar with the new technology.

District, said the problem in a nutshell was one of being unfamiliar with the new technology. culprit, probably because the cooks went with ‘piping hot’ rather than a thermometer. One web site says

culprit, probably because the cooks went with ‘piping hot’ rather than a thermometer. One web site says  the investigation. One week after the first posting, a follow-up letter was sent to those guests whose questionnaires were still to be received.

the investigation. One week after the first posting, a follow-up letter was sent to those guests whose questionnaires were still to be received.

chicken?

chicken? “Look, you may not agree with what we decided, but here’s how we came to that conclusion, and here are the assumptions we made, so you take a shot at it and see if you can do better.” That’s the fancy way to describe the role of value assumptions in risk assessments and overall risk analysis.

“Look, you may not agree with what we decided, but here’s how we came to that conclusion, and here are the assumptions we made, so you take a shot at it and see if you can do better.” That’s the fancy way to describe the role of value assumptions in risk assessments and overall risk analysis. Two lasagnas were required to feed the crew, and were cooked in the oven at the same time.

Two lasagnas were required to feed the crew, and were cooked in the oven at the same time. I attempted to call the Stouffer’s consumer hotline , but it’s only open Monday to Friday, because people don’t eat frozen entrees on the weekend.

I attempted to call the Stouffer’s consumer hotline , but it’s only open Monday to Friday, because people don’t eat frozen entrees on the weekend..jpg) "The owner of Mona Lisa pasta says his kitchen is not to blame for six central Virginia dinner guests coming down with salmonella. While he says he sold the frozen lasagna, it was not his kitchen that was responsible for cooking it to code.

"The owner of Mona Lisa pasta says his kitchen is not to blame for six central Virginia dinner guests coming down with salmonella. While he says he sold the frozen lasagna, it was not his kitchen that was responsible for cooking it to code.