Academic publishing is like the Tina Fey flick, Mean Girls. Reviewers are catty, bitchy, and snarly, all because the nerds are in power and can hide behind the cloak of anonymity.

For some reason, I usually get called in to review lousy papers, probably because I have no hesitation saying, ‘this work sucks; I could write a better paper with my butt cheeks’ or something like that.

For some reason, I usually get called in to review lousy papers, probably because I have no hesitation saying, ‘this work sucks; I could write a better paper with my butt cheeks’ or something like that.

There are so many bad papers out there.

Some geniuses at Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency decided that after 23 people died of listeria in Maple Leaf cold colds in 2008, rather than write a paper about all the mistakes that were made, they would write a paper entitled, Changing Regulation: Canada’s New Thinking on Listeria.

I have a problem with anyone who says they speak on behalf of all Canadian women, or Canadians, or other groups. Industry, don’t pay attention to this – go above and beyond because you’re going to lose money when the outbreak happens, not the bureaucrats.

The Health Canada and CFIA types proudly proclaim they’d never heard of listeria in Sara Lee hot dogs in 1998, or any other outbreak, until it happened in Canada. Now the government types have introduced what they call enhanced testing requirements.

The authors find it necessary to say that,

“Consumers also have an important role to play in the farm-to-fork continuum. That role calls for Canadians to learn and adopt safe food handling, avoidance of certain high-risk foods, and preparation practices. To this effect, Health Canada has and will continue to undertake the development of science-based consumer education material which will help create an understanding of food safety issues within the context of the public’s right to know about the potential dangers in food, and industry’s responsibility for producing a safe food. A combination of all these approaches are currently being adopted and/or developed to improve the control of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods sold in Canada.”

“Consumers also have an important role to play in the farm-to-fork continuum. That role calls for Canadians to learn and adopt safe food handling, avoidance of certain high-risk foods, and preparation practices. To this effect, Health Canada has and will continue to undertake the development of science-based consumer education material which will help create an understanding of food safety issues within the context of the public’s right to know about the potential dangers in food, and industry’s responsibility for producing a safe food. A combination of all these approaches are currently being adopted and/or developed to improve the control of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods sold in Canada.”

Wow. Guess it was the consumers’ fault that 23 died from eating crappy Maple Leaf deli meat. Or the dieticians at the aged home facilities who though it would be a bright idea to serve unheated cold-cuts to immunocomprimised old people.

This is Health Canada, the agency that still recommends whole poultry be cooked to 180F, while the U.S. recommends 165F. Are the laws of physics somehow different north of the 49th parallel? We’ve asked, and no one at Health Canada will explain, So why should they be believed on anything else?

And instead of writing crappy papers about collaborations devoid of fact, why isn’t Health Canada and the food safety types at CFIA cracking down on the BS emanating from Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Kids, which says that cold-cuts are fine for expectant moms despite a treasure-trove of scientific evidence to the contrary.

The paper concludes,

“We feel that we have learned valuable lessons from the Maple Leaf listeriosis outbreak, which occurred in 2008. We have used these lessons to help us develop CFIA Directives for federally registered meat and poultry plants. We are also learning from industry and we will use their “Best Practices” document to further develop our policies on Listeria control. By all parties working together in a non-competitive and trusting manner, we feel that we can make great strides in Listeria control and continue along a path to reducing the burden of foodborne listeriosis in Canada.”

OMG This made it into a scientific paper? I feel lots of things, but I don’t ’write them in journal articles. Here’s some tips. None of which were discussed in the so-called scientific paper:

OMG This made it into a scientific paper? I feel lots of things, but I don’t ’write them in journal articles. Here’s some tips. None of which were discussed in the so-called scientific paper:

• put warning labels on cold-cuts and other high-risk foods for expectant moms

• make listeria testing results public

• make food safety training mandatory (and then we’ll work on making it better).

And the paper is below, with the catty comments from reviewers.

I could write a better paper with my butt cheeks.

sites/default/files/Farber et al 2010_listeria.pdf

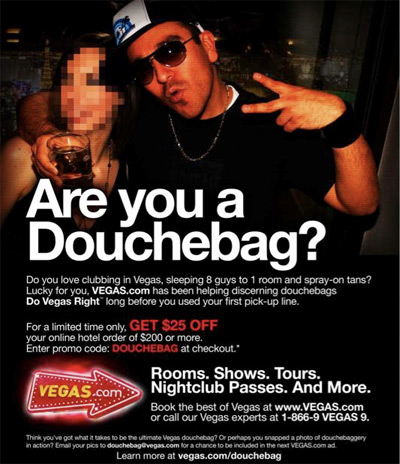

A microbiologically-challenged douchebag.

A microbiologically-challenged douchebag. Is that like fight the power? Fight the man? Fight for your right to party?

Is that like fight the power? Fight the man? Fight for your right to party? ground up – the outside, which can be laden with poop, is on the inside. With steaks, the thought has been that searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside?

ground up – the outside, which can be laden with poop, is on the inside. With steaks, the thought has been that searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside? That was 1999. I don’t see any such intact or non-intact label when I go to the grocery store. Restaurants remain a faith-based food safety institution. And the issue has rarely risen to the level of public discussion.

That was 1999. I don’t see any such intact or non-intact label when I go to the grocery store. Restaurants remain a faith-based food safety institution. And the issue has rarely risen to the level of public discussion.

Two lasagnas were required to feed the crew, and were cooked in the oven at the same time.

Two lasagnas were required to feed the crew, and were cooked in the oven at the same time. I attempted to call the Stouffer’s consumer hotline , but it’s only open Monday to Friday, because people don’t eat frozen entrees on the weekend.

I attempted to call the Stouffer’s consumer hotline , but it’s only open Monday to Friday, because people don’t eat frozen entrees on the weekend..jpg) "The owner of Mona Lisa pasta says his kitchen is not to blame for six central Virginia dinner guests coming down with salmonella. While he says he sold the frozen lasagna, it was not his kitchen that was responsible for cooking it to code.

"The owner of Mona Lisa pasta says his kitchen is not to blame for six central Virginia dinner guests coming down with salmonella. While he says he sold the frozen lasagna, it was not his kitchen that was responsible for cooking it to code.

Some of us submit our opinions to cat scratching peer review, take our lumps and get better.

Some of us submit our opinions to cat scratching peer review, take our lumps and get better. As consumers, we are inundated by media “fear-mongering,” and made to believe that with each meal consumed, we draw closer to the precipice of some fathomless tragedy. We are also taught to be suspicious and wary of the people who have dedicated their lives to ensuring that our families are fed, and that our food is wholesome.

As consumers, we are inundated by media “fear-mongering,” and made to believe that with each meal consumed, we draw closer to the precipice of some fathomless tragedy. We are also taught to be suspicious and wary of the people who have dedicated their lives to ensuring that our families are fed, and that our food is wholesome..jpg) Faith-based food safety systems are prevalent from the farmer’s market to the supermarket, especially in the produce section. And almost anything can, and is, claimed on food labels – except microbial food safety.

Faith-based food safety systems are prevalent from the farmer’s market to the supermarket, especially in the produce section. And almost anything can, and is, claimed on food labels – except microbial food safety..jpg) Maple Leaf Foods, whose listeria-laden cold-cuts killed 22 Canadians last year, is continuing on its bad

Maple Leaf Foods, whose listeria-laden cold-cuts killed 22 Canadians last year, is continuing on its bad .jpeg)

.jpg) The produce industry types responded

The produce industry types responded