Alicia Silverstone got famous in the 1995 movie, Clueless. It wasn’t particularly good or witty, and even dopey me got the whole Jane Austen thing, but it did have one memorable line, when Alicia’s Cher went into the bathroom and saw another student with bad 1980s  Motley Crue big hair, and proclaim, ‘OMG, is it 1985?’ or something like that.

Motley Crue big hair, and proclaim, ‘OMG, is it 1985?’ or something like that.

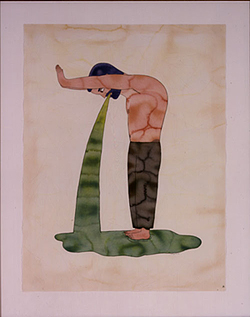

Reading the pronouncements of various U.S. food safety government-types, I want to shriek, ‘OMG, is it 1994?’ Are you still blaming consumers for getting sick?

Michael Taylor, who’s now food safety guru at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, declared in 1994 when he worked at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the government will no longer blame consumers when they get sick from nasty bacteria like E. coli O157:H7 in food. Apparently that memo hasn’t made it around Obama-change appointees.

Dr. David Goldman, assistant administrator of the Office of Public Health Science, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, said last week,

"Consumers can always protect themselves if they follow our four safe-handling guidelines: clean, separate, cook and chill. This provides some extra measure of safety."

Not for contaminated produce, pet food, pizza or pot pies.

Earlier, Jerold Mande, USDA’s deputy undersecretary for food safety told the food safety education-palooza,

“I want to be clear. At FSIS we are focused every day on preventing contaminated food from ever leaving the establishments we regulate, and we have more work to do to make our food safe. But we must also recognize that most contamination occurs after food products leave federally regulated establishments. Even if FSIS and FDA succeed in reducing illnesses from our establishments to zero, there will still be millions of foodborne illnesses and hundreds of deaths each year unless we succeed in changing the behavior of food preparers.”

Except Mande’s own USDA reported today that incoming raw poultry is the primary source of Listeria monocytogenes contamination in commercial chicken cooking plants, based on a 21-month study conducted by Agricultural Research Service (ARS) scientists and their collaborators at the University of Georgia.

Clueless.

Or at least try something new – the stuff that is out there just doesn’t work.

Or at least try something new – the stuff that is out there just doesn’t work. * While a bar graph showing the temperature distribution of the finished burgers demonstrated that many were at or near the recommended 160 degrees F, a few of the burgers’ temperatures were recorded to be much lower — as low as 112 degrees F. (Study coordinators observing consumer behavior made sure all burgers were cooked to 160 F before volunteers consumed them.)

* While a bar graph showing the temperature distribution of the finished burgers demonstrated that many were at or near the recommended 160 degrees F, a few of the burgers’ temperatures were recorded to be much lower — as low as 112 degrees F. (Study coordinators observing consumer behavior made sure all burgers were cooked to 160 F before volunteers consumed them.)