Shelly Awl, a clerk at a gas station on Cheshire Bridge Road in Atlanta, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution yesterday,

“It’s so confusing. I wish they would communicate better what is safe and what is not.”

.jpg) At a gas station in North Fulton, Karan Singh eyed with suspicion a pile of energy bars, cookies and snacks that had been laid at the check-out counter for purchase, telling a customer,

At a gas station in North Fulton, Karan Singh eyed with suspicion a pile of energy bars, cookies and snacks that had been laid at the check-out counter for purchase, telling a customer,

“I don’t think I should sell these to you. These might not be good.”

While many stores — particularly major supermarkets — appear to be keeping up with the recalls, smaller stores seem to be less consistent, according to some spot checks by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The salmonella outbreak linked to a South Georgia peanut-processing plant has spawned one of the largest product recalls in American history. The list of products that are off-limits has risen to 1,550, with new names coming out daily.

However, at Publix stores, spokeswoman Brenda Reid said recall alerts from suppliers and the FDA are immediately e-mailed to stores, which then have three hours to respond that they have removed the recalled item from the shelf. If it’s not accomplished, company managers continue to contact the store and will even send a representative there. District managers also check during their visits, she said.

The recalled item is also logged into the store’s computer, so if a customer finds one, the cashier will be alerted and will not be able to ring it up, Reid said.

Kroger stores are alerting customers who have a Kroger Plus Card of any recalled purchases through automated phone calls.

Kroger stores are alerting customers who have a Kroger Plus Card of any recalled purchases through automated phone calls.

And in a feature tomorrow, the Journal-Constitution reports federal food regulators describe the 2007 Peter Pan peanut butter salmonella outbreak traced to a Georgia plant in 2007 as “a wake-up call.” But that realization did not lead officials to scrutinize at least one other peanut processor: the Peanut Corporation of America in Blakely.

They didn’t even know the plant made peanut butter.

The FDA first learned of possible salmonella contamination at ConAgra four years ago — two years before officials traced hundreds of illnesses to Peter Pan.

In early 2005, an anonymous tipster told the FDA that ConAgra’s internal testing had detected salmonella in a batch of peanut butter the previous October, agency records show. Company executives confirmed the test results to an FDA inspector but refused to turn over lab reports unless the agency requested them in writing. The inspector left the plant, records show, and never again requested the reports.

Congressional investigators later learned that FDA policy discouraged written document requests. Federal courts, the FDA said, had ruled that if manufacturers turned over material in response to a formal request from the government, those documents could not be used as evidence in a criminal prosecution against them.

But in the vast majority of cases, investigator David Nelson told a House subcommittee in 2007, the FDA pursues neither documents nor criminal charges. Nelson termed the agency’s actions “nonsensical.”

The FDA cited no violations following the 2005 inspection in Sylvester, said Stephanie Childs, a spokeswoman for ConAgra, which is based in Omaha, Neb. Long before the inspector arrived, Childs said, the plant had destroyed the contaminated peanut butter.

This is why when companies claim they test for Salmonella, like in this ad for Jif (upper left, thanks Barb) that ran today, it’s sorta meaningless without some sort of public disclosure or oversight.

peanut butter spreads from its Peter Pan brand.

peanut butter spreads from its Peter Pan brand.

an electrician.

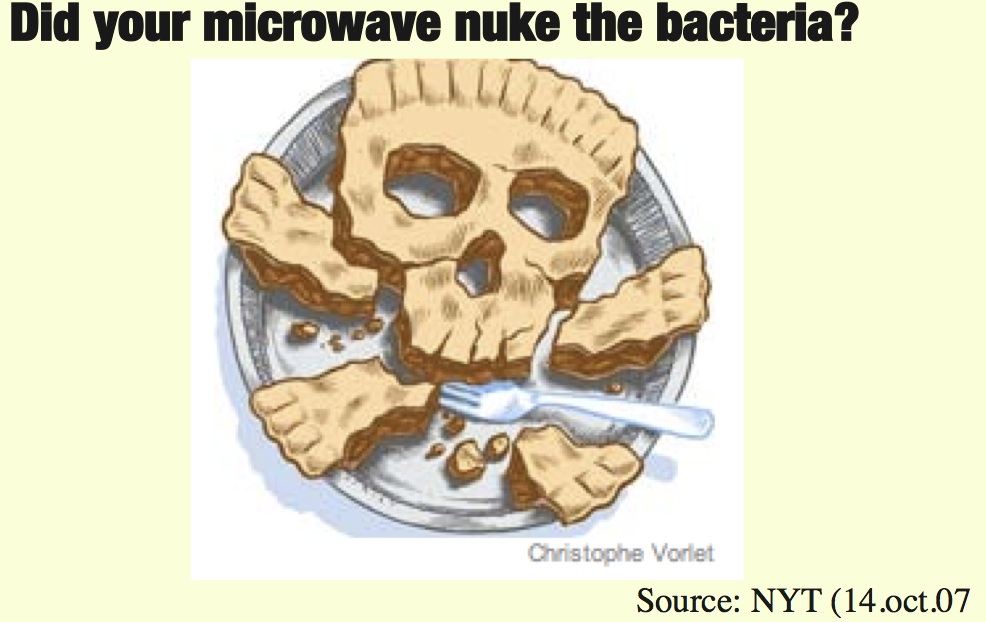

an electrician. Marie Callender‘s Cheesy Chicken & Rice frozen meal.

Marie Callender‘s Cheesy Chicken & Rice frozen meal. to be the kill step.”

to be the kill step.” Puft Marshmallows (right, exactly as shown).

Puft Marshmallows (right, exactly as shown). response and understanding of the new groovy labels that say use a meat thermometer to verify a pot pie is cooked. I did it, but I’m a nerd (left).

response and understanding of the new groovy labels that say use a meat thermometer to verify a pot pie is cooked. I did it, but I’m a nerd (left). Political opportunism. What must be reformed is the way companies – and it’s frequently ConAgra – process and produce these frozen chicken dinner thingies and they should stop blaming consumers. Lawsuits and embarrassment work far faster than political change.

Political opportunism. What must be reformed is the way companies – and it’s frequently ConAgra – process and produce these frozen chicken dinner thingies and they should stop blaming consumers. Lawsuits and embarrassment work far faster than political change. But they can still get poop in their products.

But they can still get poop in their products. A quest to find what he calls

A quest to find what he calls

.jpg) The instructions direct consumers to use a food thermometer to test the temperature. But it appears that bimetallic thermometers (traditional kitchen thermometers) are used on both the ConAgra label and in the Times video;

The instructions direct consumers to use a food thermometer to test the temperature. But it appears that bimetallic thermometers (traditional kitchen thermometers) are used on both the ConAgra label and in the Times video; (BTW,

(BTW, .jpg) And in a staggering example of corporate arrogance coupled with blame-the-consumer, Jim Seiple, a food safety official with the Blackstone unit that makes Swanson and Hungry-Man pot pies, said pot pie instructions have built-in margins of error, and the risk to consumers depended on

And in a staggering example of corporate arrogance coupled with blame-the-consumer, Jim Seiple, a food safety official with the Blackstone unit that makes Swanson and Hungry-Man pot pies, said pot pie instructions have built-in margins of error, and the risk to consumers depended on .jpg) That’s what I told

That’s what I told .jpg)

.jpg) At a gas station in North Fulton, Karan Singh eyed with suspicion a pile of energy bars, cookies and snacks that had been laid at the check-out counter for purchase, telling a customer,

At a gas station in North Fulton, Karan Singh eyed with suspicion a pile of energy bars, cookies and snacks that had been laid at the check-out counter for purchase, telling a customer, Kroger stores are alerting customers who have a Kroger Plus Card of any recalled purchases through automated phone calls.

Kroger stores are alerting customers who have a Kroger Plus Card of any recalled purchases through automated phone calls.