The U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service, and public health officials in several states investigated an outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 (STEC O157:H7) infections.

Public health investigators used the PulseNet system to identify illnesses that were part of this outbreak. PulseNet, the national subtyping network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories, is coordinated by CDC. DNA fingerprinting is performed on E. coli bacteria isolated from ill people by using a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE. PulseNet manages a national database of these DNA fingerprints to identify possible outbreaks.

Public health investigators used the PulseNet system to identify illnesses that were part of this outbreak. PulseNet, the national subtyping network of public health and food regulatory agency laboratories, is coordinated by CDC. DNA fingerprinting is performed on E. coli bacteria isolated from ill people by using a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, or PFGE. PulseNet manages a national database of these DNA fingerprints to identify possible outbreaks.

One DNA fingerprint (outbreak strain) was included in this investigation. A total of 19 people infected with the outbreak strain of Shiga toxin-producing STEC O157:H7 were reported from seven states. The majority of illnesses were reported from the western United States. The number of ill people reported from each state was as follows: California (1), Colorado (4), Missouri (1), Montana (6), Utah (5), Virginia (1), and Washington (1).

Among people for whom information was available, illnesses started on dates ranging from October 6, 2015 to November 3, 2015. Ill people ranged in age from 5 years to 84, with a median age of 18. Fifty-seven percent of ill people were female. Five (29%) people were hospitalized, and two people developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a type of kidney failure. No deaths were reported.

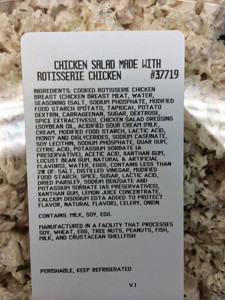

The epidemiologic evidence collected during this investigation suggested that rotisserie chicken salad made and sold in Costco stores was the likely source of this outbreak.

State and local public health officials interviewed ill people to obtain information about foods they might have eaten and other exposures in the week before their illness started. Fourteen (88%) of 16 people purchased or ate rotisserie chicken salad from Costco.

On November 20, 2015, Costco reported to public health officials that the company had removed all remaining rotisserie chicken salad from all stores in the United States. This voluntary action taken by Costco may have prevented additional illnesses. Costco also worked in collaboration with public health officials during the investigation by providing records and information related to ingredient suppliers to try to determine the source of the outbreak.

The Montana Public Health Laboratory tested a sample of celery and onion diced blend produced by Taylor Farms Pacific, Inc. and collected from a Costco store in Montana. Preliminary results indicated the presence of E. coli O157:H7. This product was used to make the Costco rotisserie chicken salad eaten by ill people in this outbreak. According to the FDA, further laboratory analysis was unable to confirm the presence of E. coli O157:H7 in the sample of celery and onion diced blend.

As a result of the preliminary laboratory results and out of an abundance of caution, on November 26, 2015, Taylor Farms Pacific, Inc. voluntarily recalled the celery and onion diced blend and many other products containing celery because they might be contaminated with E. coli O157:H7.

The FDA conducted a traceback investigation of the FDA regulated ingredients used in the chicken salad to try to determine which ingredient was linked to illness. However, the traceback investigation did not identify a common source of contamination.

This outbreak appears to be over.

diarrhea.

diarrhea..jpg) associated with illness. The chicken was cooked approximately 24 hours before serving and not cooled in accordance with hospital guidelines. C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) was detected in 20 of 23 stool specimens from ill residents and staff members. Genetic testing of C. perfringens toxins isolated from chicken and stool specimens was carried out to determine which of the two strains responsible for C. perfringens foodborne illness was present. The specimens tested negative for the beta-toxin gene, excluding C. perfringens type C as the etiologic agent and implicating C. perfringens type A. This outbreak underscores the need for strict food preparation guidelines at psychiatric inpatient facilities and the potential risk for adverse outcomes among any patients with impaired intestinal motility caused by medications, disease, and extremes of age when exposed to C. perfringens enterotoxin.

associated with illness. The chicken was cooked approximately 24 hours before serving and not cooled in accordance with hospital guidelines. C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE) was detected in 20 of 23 stool specimens from ill residents and staff members. Genetic testing of C. perfringens toxins isolated from chicken and stool specimens was carried out to determine which of the two strains responsible for C. perfringens foodborne illness was present. The specimens tested negative for the beta-toxin gene, excluding C. perfringens type C as the etiologic agent and implicating C. perfringens type A. This outbreak underscores the need for strict food preparation guidelines at psychiatric inpatient facilities and the potential risk for adverse outcomes among any patients with impaired intestinal motility caused by medications, disease, and extremes of age when exposed to C. perfringens enterotoxin. mayonnaise does not cause foodborne illness.

mayonnaise does not cause foodborne illness. and associate administrator at Central Louisiana State Hospital have, as they politely say in the South (and smile while the knife goes in), left the facility.

and associate administrator at Central Louisiana State Hospital have, as they politely say in the South (and smile while the knife goes in), left the facility.