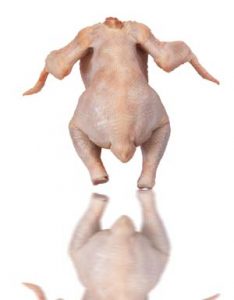

About one third of foodborne illness outbreaks in Europe are acquired in the home and eating undercooked poultry is among consumption practices associated with illness. The aim of this study was to investigate whether actual and recommended practices for monitoring chicken doneness are safe.

Seventy-five European households from five European countries were interviewed and videoed while cooking chicken in their private kitchens, including young single men, families with infants/in pregnancy and elderly over seventy years. A cross-national web-survey collected cooking practices for chicken from 3969 households. In a laboratory kitchen, chicken breast fillets were injected with cocktails of Salmonella and Campylobacter and cooked to core temperatures between 55 and 70°C. Microbial survival in the core and surface of the meat were determined. In a parallel experiment, core colour, colour of juice and texture were recorded. Finally, a range of cooking thermometers from the consumer market were evaluated.

Seventy-five European households from five European countries were interviewed and videoed while cooking chicken in their private kitchens, including young single men, families with infants/in pregnancy and elderly over seventy years. A cross-national web-survey collected cooking practices for chicken from 3969 households. In a laboratory kitchen, chicken breast fillets were injected with cocktails of Salmonella and Campylobacter and cooked to core temperatures between 55 and 70°C. Microbial survival in the core and surface of the meat were determined. In a parallel experiment, core colour, colour of juice and texture were recorded. Finally, a range of cooking thermometers from the consumer market were evaluated.

The field study identified nine practical approaches for deciding if the chicken was properly cooked. Among these, checking the colour of the meat was commonly used and perceived as a way of mitigating risks among the consumers. Meanwhile, chicken was perceived as hedonically vulnerable to long cooking time. The quantitative survey revealed that households prevalently check cooking status from the inside colour (49.6%) and/or inside texture (39.2%) of the meat. Young men rely more often on the outside colour of the meat (34.7%) and less often on the juices (16.5%) than the elderly (>65 years old; 25.8% and 24.6%, respectively). The lab study showed that colour change of chicken meat happened below 60°C, corresponding to less than 3 log reduction of Salmonella and Campylobacter. At a core temperature of 70°C, pathogens survived on the fillet surface not in contact with the frying pan. No correlation between meat texture and microbial inactivation was found. A minority of respondents used a food thermometer, and a challenge with cooking thermometers for home use was long response time. In conclusion, the recommendations from the authorities on monitoring doneness of chicken and current consumer practices do not ensure reduction of pathogens to safe levels. For the domestic cook, determining doneness is both a question of avoiding potential harm and achieving a pleasurable meal. It is discussed how lack of an easy “rule-of-thumb” or tools to check safe cooking at consumer level, as well as national differences in contamination levels, food culture and economy make it difficult to develop international recommendations that are both safe and easily implemented.

Cooking chicken at home: common or recommended approaches to judge doneness may not assure sufficient inactivation of pathogens, 29 April 2020

PLOS One

Solveig Langsrud, Oddvin Sørheim, Silje Elisabeth Skuland, Valérie Lengard Almli, Merete Rusås Jensen, Magnhild Seim Grøvlen, Øydis Ueland, Trond Møretrø

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230928

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0230928