The three weeks I spent in France in 2007 with my French-professor wife were memorable on many accounts. Like anywhere else, when I met people and they found out I was involved in food safety, they would tell me their  worst barf stories. What was unique was the patriotic-like duty many of the sufferers felt about not reporting any foodborne illness to health-types.

worst barf stories. What was unique was the patriotic-like duty many of the sufferers felt about not reporting any foodborne illness to health-types.

Dr. Mathieu Tourdjman, a French physician who’s currently working at Oregon Public Health in Portland, helped investigate the Sally Jackson cheese mess under the supervision of Bill Keene.

As reported by Lynne Terry of The Oregonian, food is recalled in France but that country does not have a wealth of epidemiologists to investigate outbreaks.

"We don’t have such a developed public health system," said Tourdjman, "and all those epidemiologists know each other and are perfectly happy to cooperate."

To help identify the woman who made raw milk cheese while covered in cow poop, Keene (below, right, photo from The Oregonian) and colleagues at Oregon Public Health offered a unique case study in epidemiology 101.

To this day, no one sickened remembers consuming Sally Jackson cheese. But epidemiologists managed to pinpoint it anyway.

"I can’t recall another outbreak with so many cases and a multi-state outbreak with none of the cases remembering eating the food," said William Keene, senior epidemiologist with Oregon Public Health.

About two weeks ago, Keene found out about two cases of E. coli O157 in Roseburg. Both were women in their early 60s. They didn’t know each other  but their demographic similarity sent up red flags, indicating a possible wider outbreak.

but their demographic similarity sent up red flags, indicating a possible wider outbreak.

Tourdjman quickly caught on. Under Keene’s guidance, he discovered another E. coli case in Vancouver. Turns out that that woman and one of the women in Roseburg had dined one day apart at Clarklewis Restaurant in Southeast Portland.

Not only that, they had both ordered the artisan cheese plate as a starter.

Clarklewis officials could not identify the cheese they ate. But the restaurant’s invoices provided a list of suspects. They included Sally Jackson cheese.

"That was the start, and it turned out to be critical," Keene said. "We assumed that whatever was causing the outbreak was at the restaurant."

Then another Washington connection popped up with a woman who had shopped at Calf & Kid, an artisan cheese store in Seattle.

The shop’s website mentioned Sally Jackson cheese — yet another coincidence.

Then, Keene and Tourdjman discovered that Jackson, an artisan cheesemaker in Oroville near the Canadian border, was threatened with a possible shutdown by Washington state over sanitation concerns.

With Sally Jackson on their radar, the Oregon epidemiologists discovered more cases, including a man in Vermont and one in Seattle.

The Vermont man had visited his uncle in Seattle and eaten at Palace Kitchen, a high-end restaurant that serves Sally Jackson cheese. And the man in  Seattle had attended a wedding in Tonasket, Wash., just south of Oroville. The wedding featured local cheese — probably from Sally Jackson.

Seattle had attended a wedding in Tonasket, Wash., just south of Oroville. The wedding featured local cheese — probably from Sally Jackson.

The scientists had circumstantial evidence. Now, they needed proof. Keene sought Sally Jackson cheese from Oregon restaurants to test for E. coli. Very few had any. Tina’s Restaurant in Dundee had thrown some away. The owner retrieved it by diving into her Dumpster.

In the end, at least two samples of Sally Jackson’s cheese tested positive for E. coli O157:H7, confirming it was the source of the outbreak that sickened eight and involved investigators from four states and the Food and Drug Administration.

Last Friday, less than two weeks after Tourdjman started the investigation, Jackson pulled all her cheese off the market.

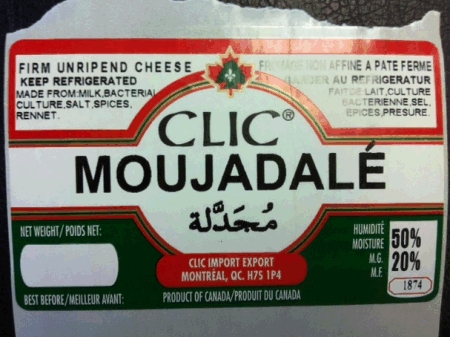

monocytogenes in samples of All Natural Chives Cheese that were collected from Green Cedar Dairy.

monocytogenes in samples of All Natural Chives Cheese that were collected from Green Cedar Dairy.

several products had been missed. The manufacturer has ceased production at its facilities and the CFIA working with them to make sure other products manufactured by the company are safe to consume.”

several products had been missed. The manufacturer has ceased production at its facilities and the CFIA working with them to make sure other products manufactured by the company are safe to consume.”.jpg) a Salt Lake City restaurant/deli.

a Salt Lake City restaurant/deli..jpg) food safety agencies here and there,

food safety agencies here and there,  to kill harmful bacteria, a process known as pasteurization. So aging allows the chemicals in cheese, acids and salt, time to destroy harmful bacteria.

to kill harmful bacteria, a process known as pasteurization. So aging allows the chemicals in cheese, acids and salt, time to destroy harmful bacteria. (1)(1).jpg) eight people in four states were sickened by bacteria traced to soft cheeses made by Sally Jackson, a pioneering cheesemaker in Oroville, Wash.

eight people in four states were sickened by bacteria traced to soft cheeses made by Sally Jackson, a pioneering cheesemaker in Oroville, Wash. (1).jpg) for more than a year.

for more than a year.

(1).jpg) The artisan cheese maker temporarily shut down.

The artisan cheese maker temporarily shut down..jpg) • no more ground beef;

• no more ground beef; but their demographic similarity sent up red flags, indicating a possible wider outbreak.

but their demographic similarity sent up red flags, indicating a possible wider outbreak.  Seattle had attended a wedding in Tonasket, Wash., just south of Oroville. The wedding featured local cheese — probably from Sally Jackson.

Seattle had attended a wedding in Tonasket, Wash., just south of Oroville. The wedding featured local cheese — probably from Sally Jackson.  may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed.

may have become soiled or contaminated. Specifically, the owner was observed throughout the day to altemately perform cheese making functions, such as stirring cheese curd with bare hands and wrapping cheese in grape leaves, with outside activities, such as milking/feeding livestock, without any hand washing being observed. .jpg) brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket.

brushed pants with a bare hand and was later observed standing over a bucket of drained curd in the cheese room with the soiled pants coming in to contact with the edge of the bucket.