Lawsuits filed by victims of a 2011 Listeria outbreak that killed four New Mexicans and severely sickened a fifth raise questions about the effectiveness of food safety inspections required by many retailers.

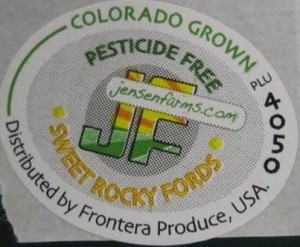

The New Mexico victims were among 33 people killed nationally by bacterial infections linked to cantaloupes grown at a farm in Colorado, making it one of the deadliest outbreaks of food-borne illness in U.S. history.

A focus of the five New Mexico lawsuits, and dozens of others in the U.S., is a California food safety auditing firm, PrimusLabs, that gave the Colorado cantaloupe packing  operation a score of 96 percent and a “superior” rating just weeks before the outbreak, the lawsuits contend.

operation a score of 96 percent and a “superior” rating just weeks before the outbreak, the lawsuits contend.

The New Mexico lawsuits, filed in U.S. District Court in Albuquerque, also name Walmart Stores, where the families say they purchased the tainted cantaloupes, and Frontera Produce, a Texas-based produce distributor.

A contractor hired by PrimusLabs inspected Jensen Farms in July 2011 and gave the cantaloupe packing operation the superior rating, allowing it to continue selling cantaloupes, the lawsuits contend.

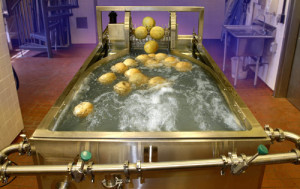

In September 2011, health officials announced a multistate Listeria outbreak that ultimately infected 147 people in 28 states, including 15 in New Mexico. Later that month, federal and Colorado health officials inspected Jensen Farms, finding 13 confirmed samples of Listeria strains linked to the outbreak.

PrimusLabs Corp. is seeking dismissal of a civil case filed against the audit firm by cantaloupe growers Eric and Ryan Jensen, placing blame on the brothers and distributor Frontera Produce.

Even though an audit in July 2011 — conducted by BFS for PrimusLabs — gave the Jensens packing shed a score of 96 out of 100 and a “superior” rating, PrimusLabs contends the Jensens should not have assumed their cantaloupes were “fit for human consumption.”

PrimusLabs described the audit as “non-descript” in court documents. The audit company contends it did not create a risk that otherwise did not exist and that there is no reason to think Jensen Farms would have not shipped cantaloupe if it had received a poor audit score.

“If Jensen wanted to protect consumers from its products, it could have contracted with some third party to conduct the requisite environmental testing and inspection,” PrimusLabs states in court documents.

What we found when investigating the audit issue, long before this 2011 outbreak, was:

• food safety audits and inspections are a key component of the nation’s food safety system and their use will expand in the future, for both domestic and imported foodstuffs., but recent failures can be emotionally, physically and financially devastating to the victims and the businesses involved;

• many outbreaks involve firms that have had their food production systems verified and received acceptable ratings from food safety auditors or government inspectors;

• while inspectors and auditors play an active role in overseeing compliance, the burden  for food safety lies primarily with food producers;

for food safety lies primarily with food producers;

• there are lots of limitations with audits and inspections, just like with restaurants inspections, but with an estimated 48 million sick each year in the U.S., the question should be, how best to improve food safety?

• audit reports are only useful if the purchaser or food producer reviews the results, understands the risks addressed by the standards and makes risk-reduction decisions based on the results;

• there appears to be a disconnect between what auditors provide (a snapshot) and what buyers believe they are doing (a full verification or certification of product and process);

• third-party audits are only one performance indicator and need to be supplemented with microbial testing, second-party audits of suppliers and the in-house capacity to meaningfully assess the results of audits and inspections;

• companies who blame the auditor or inspector for outbreaks of foodborne illness should also blame themselves;

• assessing food-handling practices of staff through internal observations, externally-led evaluations, and audit and inspection results can provide indicators of a food safety culture; and,

• the use of audits to help create, improve, and maintain a genuine food safety culture holds the most promise in preventing foodborne illness and safeguarding public health.

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

30.aug.12

Food Control

D.A. Powell, S. Erdozain, C. Dodd, R. Costa, K. Morley, B.J. Chapman

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713512004409?v=s5

Abstract

Internal and external food safety audits are conducted to assess the safety and quality of food including on-farm production, manufacturing practices, sanitation, and hygiene. Some auditors are direct stakeholders that are employed by food establishments to conduct internal audits, while other auditors may represent the interests of a second-party purchaser or a third-party auditing agency. Some buyers conduct their own audits or additional testing, while some buyers trust the results of third-party audits or inspections. Third-party auditors, however, use various food safety audit standards and most do not have a vested interest in the products being sold. Audits are conducted under a proprietary standard, while food safety inspections are generally conducted within a legal framework. There have been many foodborne illness outbreaks linked to food processors that have passed third-party audits and inspections, raising questions about the utility of both. Supporters argue third-party audits are a way to ensure food safety in an era of dwindling economic resources. Critics contend that while external audits and inspections can be a valuable tool to help ensure safe food, such activities represent only a snapshot in time. This paper identifies limitations of food safety inspections and audits and provides recommendations for strengthening the system, based on developing a strong food safety culture, including risk-based verification steps, throughout the food safety system.

cantaloupe outbreak — is now suing the grower, distributor and the grower’s third-party auditor.

cantaloupe outbreak — is now suing the grower, distributor and the grower’s third-party auditor.