The number of confirmed sick people linked to beef from the XL plant in Alberta has risen to 16, the plant is eager to reopen but a former employee says CFIA sucks at inspection,  and major media taunt pretty much everyone, especially the terrible communication from government types.

and major media taunt pretty much everyone, especially the terrible communication from government types.

André Picard of the Globe and Mail says that with 16 people sick with E. coli O157:H7, “It’s not the most lethal public-health problem we have ever had in this country, but the

response has to rank among the most ridiculous.

“The response to tainted beef from officialdom has largely been buffoonery: The Agri-Business Minister chowing down on beef at a Rotary luncheon at the height of the crisis; the Alberta Premier saying her 10-year-old daughter has eaten beef every day since the recall; the Wildrose Leader saying the suspect meat should be used to feed the poor and so on.

“The clear message behind these “don’t worry, be happy” displays is that the interests of business matter more than the health of consumers. Sadly, the anti-consumer bias is built into our government structure.

“We have a federal Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Business, and Gerry Ritz has played the industry-booster role well, repeatedly expressing his concern for XL Foods, the cattle industry and the economy of Brooks, Alta. But he has been all but silent on those who have been sickened and on the safety of consumers more generally.

“What we don’t have is a minister of food to give voice to the millions who actually eat food and a Canadian Food Inspection Agency not under the ministerial thumb and whose  overriding priority is ensuring safe and pathogen-free food on our dinner tables.

overriding priority is ensuring safe and pathogen-free food on our dinner tables.

“Our political leaders – federal and provincial – behave as if food safety is solely the responsibility of individual consumers, and it is troubling that they are using public agencies to deliver this wrong-headed message.

“Consumers should not be responsible for cooking their meat to death to kill E.coli any more than they should be responsible for pasteurizing their own milk or boiling their tap water before drinking it.

“Food-safety regulations should be designed and enforced to protect the public, not industry. The folks at Health Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency should be allowed to do their jobs, unfettered. They should not be reduced to issuing asinine press releases to mollify the powers that be.”

What follows is finger-pointing from various media accounts.

One consultant lobbyist who is also a communications expert who did not want to be named (how Canadian) told The Hill Times last week that Minister of Agriculture Gerry Ritz’s strategy is worse than when more than 23 people died in 2008 from listeriosis.

The lobbyist added, Mr. Ritz has no effective key messages that he’s been delivering. “I mean what’s the message track? You can’t just repeat that public safety is our number one priority while people are falling over sick around the country and puking their guts out. There’s no credibility.”

A former XL Foods Inc. manager who now works as a food safety consultant, told CBC News federal inspectors lack sufficient training.

Former XL Foods quality assurance manager Jacci Dorran said CFIA inspectors often knew less about their own food safety requirements than her employees.

Dorran worked at XL Foods for 10½ years until August 2006.

Dorran said she watched as the CFIA was created in 1997 and followed its evolution.

“It was very common that my staff was training the CFIA,” said Dorran.

“They weren’t necessarily going out into the plant. They might just show up there and read the paper, do the crossword puzzles,” she said.

“They need to be helping the meat industry so we don’t get to this point.”

Dorran said the CFIA problem started when the CFIA started requiring plants to have “hazard analysis critical control point” (HACCP) plans.

“The new philosophy is give us a bunch of paperwork and then we spend more time filling out paperwork on how we’re supposed to fix it other than actually being out on the floor and fix it ourselves — that really bothered me.”

It also emerged that XL is fighting allegations that one of its plants was the source eight years ago of tainted meat that left a young child severely disabled.

Federal government reports indicate as many as 26 other people may also have become sick in 2004 from the same genetic strain of bacteria found in product that a lawsuit claims came from an XL Foods facility.

The company argues it bears no liability for a Winnipeg boy who a legal action claims lost mobility in three limbs, suffers developmental delays and endures severe, ongoing pain caused by eating food containing ground meat tainted with the potentially-fatal bacteria.

Kathy Richard says a few bowls of hamburger soup her grandson ate landed him in hospital for 17 months and left him with no hope of a normal life.

“He was a muscular, little two-and-a-half year old who loved to wrestle and ride his toy motorcycle,” Richard said.

“Now he’s in a wheelchair, wears diapers, and has to be fed through a tube in his stomach.”

Richard is angry that XL Foods is accepting responsibility for the current E. coli cases, but blaming her daughter for what happened eight years ago.

“It’s upsetting,” she said.

“I wonder how they were able to make the same mistake. Did they not learn from the last time?”

Richard says she calls her grandson a “miracle boy,” who managed to survive his medical ordeal after receiving a kidney transplant.

But she said he still suffers from occasional seizures and is only able to communicate by making noises that family members and caregivers understand.

Inspection Agency, which reports to Ritz.

Inspection Agency, which reports to Ritz.

bacteria.

bacteria..jpg) A lot.

A lot.

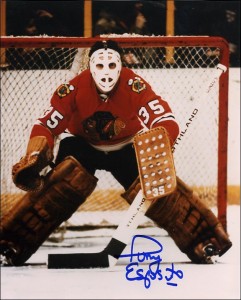

That’s Sorenne with teacher Nancy at pre-school. Nancy was born in Arnprior, raised in Pembroke that’s near Ottawa, in Canada (hello Alanis).

That’s Sorenne with teacher Nancy at pre-school. Nancy was born in Arnprior, raised in Pembroke that’s near Ottawa, in Canada (hello Alanis).