Between the anguished cries in the fetal position after his beloved Boston Bruins were bumped out of the Stanley Cup playoffs (that’s ice hockey to Australians), my cousin, Tim Barrie, manages to carry on the family tradition and farm asparagus.

It’s a late spring in southern Ontario (Cambridge area, to be specific), but Tim says the flavor is great and Tim is always finding the bright side.

And he knows enough to practice good food safety.

And he knows enough to practice good food safety.

According to the K-W Record, green and sweet asparagus is what spring is all about his 25-acre farm off Kings Road.

Blame a hard snowy winter and a wet spring for a tardy crop at Barrie’s Asparagus Farm, but the good news is it’s lip-smacking luscious and sweet-pea scrumptious.

Two years ago, drought made for a bitterly disappointing harvest, said 52-year-old Tim Barrie. Last year was a great crop for quantity. This year, quality binds every $3-a-pound bunch.

“Taste-wise, it’s as good as I can remember,” Barrie said from beneath his favorite spoked-number-four Bobby Orr ball cap.

This asparagus operation goes back four decades on this former cattle farm. The future is asparagus, Barrie’s father David was told by his father-in-law Homer — an Alliston asparagus grower.

David, who still trims the grass at the farm (and still plays pickup hockey at 80- years-old), listened and became a spear plucker.

His son Tim and his wife Libby run the fields of green and the farmhouse shop now.

Their grown daughters — Mallory, Emily and Hannah — and son Will, 13, help out too.

There are only about 100 asparagus operations in Ontario because it’s labor-intensive. Barrie has 10 locally hired pickers harvesting his 24 acres every day until Canada Day. The spears are spun right into the farmhouse shop and put on sale within an hour of picking off the side of Kings Road.

There are only about 100 asparagus operations in Ontario because it’s labor-intensive. Barrie has 10 locally hired pickers harvesting his 24 acres every day until Canada Day. The spears are spun right into the farmhouse shop and put on sale within an hour of picking off the side of Kings Road.

On Saturday mornings, the parked cars fill up the country roundabout in front of the house, Barrie said. They come for the fresh asparagus. They may leave with pickled asparagus and asparagus barbecue sauce, too. Or asparagus ravioli and asparagus soap. Or asparagus salsa. A fresh batch of that salsa, bottled with a day of picking, is firehouse hot.

They plant strawberries too, along with rhubarb, sweet corn and pumpkins.

They sell some kettle chips, named Spud’s Finest in honour of Barrie’s mother Miriam (she’s my mom’s sister – dp). She grew up on a potato farm before her father turned to, of course, asparagus.

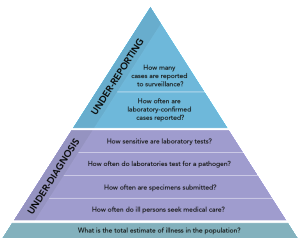

Food minister, Dan Jørgensen, has blasted the food authorities, Fødevarestyrelsen, over its handling of the Listeria outbreak that has claimed the lives of 12 people in Denmark over the past year.

Food minister, Dan Jørgensen, has blasted the food authorities, Fødevarestyrelsen, over its handling of the Listeria outbreak that has claimed the lives of 12 people in Denmark over the past year.