I must be getting old that I can remember news from 25 years ago and today’s journalists can’t even be bothered to look at wiki.

Canada’s new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, took office on 4 November — and as one of his first acts, created the post of Minister of Science.

Canada’s new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, took office on 4 November — and as one of his first acts, created the post of Minister of Science.

Except it was done in 1990.

I was the first journalist to interview Bill Winegard when he was named Canada’s first Minister of Science in 1990. Guelph (that’s in Canada), where Winegard had served as university president, was still viewed as a cow-town by the uppities in Ottawa, and what was with all this science stuff?

Bill was always generous with his time, and quick with a barb. He’s still fighting the good fight at 91. As a public figure, we university journos had fun with Bill, but he took it all in stride, and I can’t think of a better representative for Guelph.

Below is from the Guelph Mercury last year, and apt as Remembrance Day approaches.

Bill Winegard is a Second World War veteran, a former federal government cabinet minister and a past president of the University of Guelph

Next May will be 100 years since a man from Guelph, John McCrae, wrote the most popular and the most renowned poem of the First World War. He was a doctor, a soldier and a true humanitarian. To understand the significance of the poem and our fight for freedom, let us take a trip.

Let us go to Flanders Fields.

Let us go to Wimereux Cemetery in France, a relatively small cemetery where as we walk amidst the headstones of the 200 young Canadians buried there we pause at the headstone of Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae.

Still in France, we move on to Beny sur Mer Canadian War Cemetery, where surrounded by pine and maple trees, 2,049 young Canadians are buried, most having lost their lives during the D-Day fighting and the Battle for Caen.

To Holland now, and to the largest Canadian War Cemetery in the Netherlands—Groesbeek, where there are 2,338 graves.

If we travel to Denmark, to the War Cemetery in Esbjerg, among the 247 Commonwealth graves we will find a grave marked James Shield Norton, aged 20 years, from Caledonia, Ontario. He was my best friend.

In Italy, we will stop at the cemetery at Ortona, which contains the graves of hundreds of D-Day dodgers.

If we travel to Korea, we will find the graves of the 516 soldiers who lost their lives in that conflict.

Even before the First World War, Canada was part of the Boer War. We sent 8,000 troops, including my grandfather. Two hundred fifty Canadians died.

Even before the First World War, Canada was part of the Boer War. We sent 8,000 troops, including my grandfather. Two hundred fifty Canadians died.

In the First World War, Canada, with a population of roughly eight million, had 640,000 people in uniform, including my grandfather and father. Seventy-two thousand were killed and 175,000 wounded—one of which was my father at age 16. Forty Canadians died each day. One in 10 Canadians did not come home, including 219 from Guelph.

In the Second World War, Canada’s population was 12 million, with one million in uniform, including me and my father and some present here today. Fifty thousand were killed and about 60,000 wounded. Many of my friends were among the 50,000 killed. Twenty Canadians were killed each day over a six-year period, 40 wounded and five taken prisoners of war. Guelph lost 171 soldiers.

In the Korean War, we had 34,000 troops there—more than most people think—with over 500 killed. One of those was from Guelph.

We can’t forget our peacekeepers – really, peacemakers. We have had 113 soldiers killed in the over 50 United Nations missions we have participated in from Zaire to Afghanistan.

Canada’s fighting participation in the conflict in Afghanistan ended this year. We should acknowledge and pay tribute to our exceptionally impressive troops, including the 11th Field Regiment. Canadians showed their respect by lining the bridges and roadways as the bodies were returned to Canada. One hundred fifty-eight hearses travelled down the Highway of Heroes.

There is another set of numbers that is even more shocking. Between the years 2004 and 2014, 160 military personnel have taken their own lives. That means the Canadian military has lost more soldiers to suicide than it did to combat in Afghanistan. These soldiers were very ill and needed help. They needed much more help than was available and they needed care of a special nature.

Instead of being sensitive to the issues, the Government of Canada seemed oblivious to the precarious mental state that many veterans were—and are—battling. For many, professional help was not available. For others, they had to cope with an insensitive government that even changed their point of contact by closing nine regional offices. These offices were familiar places to the veterans and, for the most part, they felt comfortable and safe. But, apparently to reduce costs, they were sent to unfamiliar places hours away, which caused further mental stress. This seems a relatively small matter to us but to the veteran it was one more issue where government seemed to back away from concerns raised in the new Veterans Charter.

The apparent callousness of the Department of Veterans Affairs was further made apparent when, in a class-action suit filed by disabled soldiers, Crown lawyers argued that today’s government shouldn’t be held to historical promises! What a cold-hearted thing to say! If veterans can’t count on government promises, it is a very sad day indeed.

When the Veterans Charter was introduced some years ago, it was welcomed as a way to support the veterans financially, with an understanding that it would be amended as needed. It hasn’t really worked out to the benefit of the veterans. THE GOVERNMENT SPENT BILLIONS PURSUING THE WAR, YET WON’T SPEND THE MILLIONS NESSECARY TO HELP OUR CURRENT VETERANS.

No one seems to have thought of using the spirit of “esprit de corps” to help. By that, I mean there are many veterans that are willing to help their comrades. While those suffering from post traumatic stress disorder need professional help, they could also use the listening ability of former comrades.

It would not be difficult to have former comrades standing by to listen and talk with former or current soldiers in difficulty. Esprit de corps is a very powerful force. Waiting for the veteran to come forward does not and will not work. We must find a way to go to them.

We are once again at war. How sad we are sending more of our men off to battle when we haven’t even resolved the issues left over from Afghanistan. We have to do a much better job taking care of our veterans.

In 1984 there were unresolved issues between the government and veterans. In caucus one day, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney said to the then minister of veterans affairs, the Honourable George Hees, “George, in any dispute between the veteran and the government, the veteran will always be given the benefit of the doubt.” Let us get serious about the health and welfare of the veterans who have served our country. We need a similar declaration from the current government!

Over the past 100 years or more, our veterans and comrades have gone to war. They paid a heavy price for our freedom. It was hard won. Many veterans returning home have counted on Canada doing the honourable thing by taking care of them and their families on their return. We say to the Minister of Veterans Affairs—Minister Fantino—FIX THIS PROBLEM!

We must never forget the sacrifices made. We Will Remember.

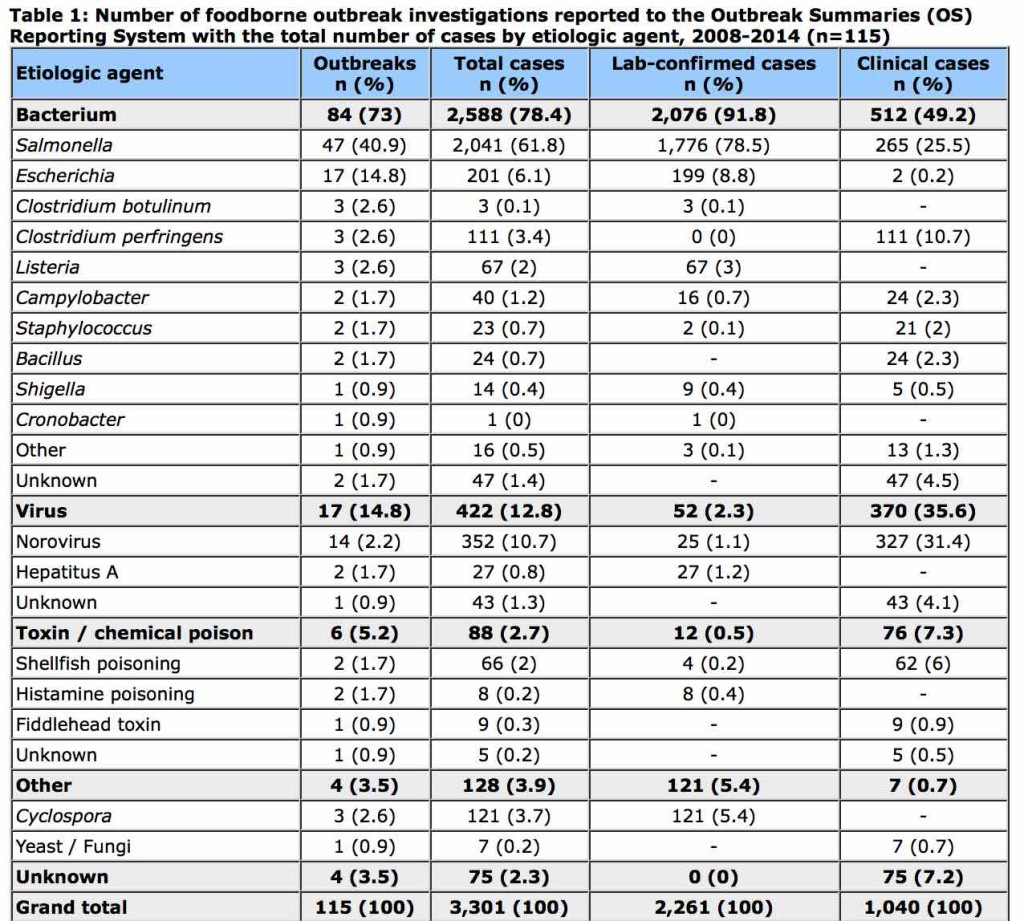

Although the magnitude of drinking water-related illnesses in developed countries is lower than that observed in developing regions of the world, drinking water is still responsible for a proportion of all cases of acute gastrointestinal illness (AGI) in Canada.

Although the magnitude of drinking water-related illnesses in developed countries is lower than that observed in developing regions of the world, drinking water is still responsible for a proportion of all cases of acute gastrointestinal illness (AGI) in Canada.