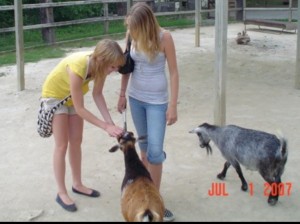

Animal contact is a potential transmission route for campylobacteriosis, and both domestic household pet and petting zoo exposures have been identified as potential sources of exposure.

Research has typically focussed on the prevalence, concentration, and transmission of zoonoses from farm animals to humans, yet there are gaps in our understanding of these factors among animals in contact with the public who don’t live on or visit farms.

Research has typically focussed on the prevalence, concentration, and transmission of zoonoses from farm animals to humans, yet there are gaps in our understanding of these factors among animals in contact with the public who don’t live on or visit farms.

This study aims to quantify, through a systematic review and meta-analysis, the prevalence and concentration of Campylobacter carriage in household pets and petting zoo animals. Four databases were accessed for the systematic review (PubMed, CAB direct, ProQuest, and Web of Science) for papers published in English from 1992–2012, and studies were included if they examined the animal population of interest, assessed prevalence or concentration with fecal, hair coat, oral, or urine exposure routes (although only articles that examined fecal routes were found), and if the research was based in Canada, USA, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Studies were reviewed for qualitative synthesis and meta-analysis by two reviewers, compiled into a database, and relevant studies were used to create a weighted mean prevalence value. There were insufficient data to run a meta-analysis of concentration values, a noted study limitation.

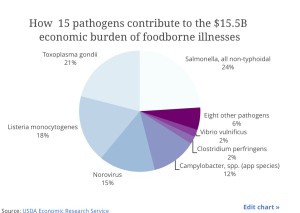

The mean prevalence of Campylobacter in petting zoo animals is 6.5% based on 7 studies, and in household pets the mean is 24.7% based on 34 studies. Our estimated concentration values were: 7.65x103cfu/g for petting zoo animals, and 2.9x105cfu/g for household pets. These results indicate that Campylobacter prevalence and concentration are lower in petting zoo animals compared with household pets and that both of these animal sources have a lower prevalence compared with farm animals that do not come into contact with the public.

There is a lack of studies on Campylobacter in petting zoos and/or fair animals in Canada and abroad. Within this literature, knowledge gaps were identified, and include: a lack of concentration data reported in the literature for Campylobacter spp. in animal feces, a distinction between ill and diarrheic pets in the reported studies, noted differences in shedding and concentrations for various subtypes of Campylobacter, and consistent reporting between studies.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Campylobacter spp. prevalence and concentration in household pets and petting zoo animals for use in exposure assessments

18.dec.15

PLoS ONE 10(12): e0144976

Pintar KDM, Christidis T, Thomas MK, Anderson M, Nesbitt A, Keithlin J, et al.

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144976