Crows are smart, highly social animals that congregate in flocks of tens of thousands. Such large, highly concentrated populations can easily spread disease — not only amongst their own species, but quite possibly to humans, either via livestock, or directly.

On the campus of the University of California, Davis, during winter, approximately half of the 6,000 American crows that congregated at the study site carried Campylobacter jejuni, which is the leading cause of gastroenteritis in humans in industrialized countries, which could contribute to the spread of disease. The research is published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

On the campus of the University of California, Davis, during winter, approximately half of the 6,000 American crows that congregated at the study site carried Campylobacter jejuni, which is the leading cause of gastroenteritis in humans in industrialized countries, which could contribute to the spread of disease. The research is published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

The investigators posited that the crows’ daily wanderings contributed to C. jejuni’s spread. To track the crows, they trapped a small number of individuals and attached tiny GPS devices to diminutive backpacks. They affixed these to the birds with harnesses that looped around each wing to attach at the breast. The additional weight represented less than one twentieth that of the crows.

The crows’ favored destinations were areas with easy access to food, such as a dairy barn, and a primate research center. “This movement pattern, coupled with high infection rates, suggests that crows could play an important role in transmission from wild birds to domestic animals and, ultimately, to humans,” said first author Conor Taff, PhD.

Crows are also strong flyers, and able to spread contamination far from the roost.

Crows’ social behavior also probably contributes to the pathogen’s spread. Their communal winter roosts can pack thousands of crows into a few trees each night, said Taff, a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, who conducted some of the research while he was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Davis. And crowds of crows, opportunistic omnivores, forage together, defecating where they eat. “These things together probably explain why crows have such high prevalence of infection compared to other wild birds,” said Taff.

Crows’ opportunistic foraging frequently leads them to live in proximity to humans, and to livestock, putting us at risk for infection. Among other places, crows forage at livestock feedlots and in fields containing particular crops.

Nonetheless, data is lacking on the prevalence of crow-borne strains of C. Jejuni that have the potential either to infect humans, or to easily mutate to infect humans. (A coauthor on this paper, Allison M. Weis of the School of Veterinary Medicine, Pathogen Genome Project, University of California, Davis, is working on that issue.) Nor is it clear whether Campylobacter sickens crows — another issue which team members are investigating.

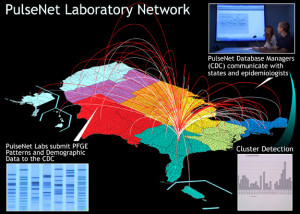

“Our study is just a start, but our results suggest that integrative work that combines microbiology, ecology, and behavior is likely to be important in controlling cross-species transmission of Campylobacter,” said Taff. “Since wild birds may be an important source of initial poultry infection, it is important to understand how infection persists in wild birds and how their behavior might contribute to domestic animal infection. Our movement data are particularly interesting in this regard, because we found that crows were making heavy use of some areas with domestic animals.”

“Understanding how both this behavior and infection rates vary across the year might make it possible to devise mitigation strategies that exclude wild animals from interacting with domestic animals in certain places or at certain times of the year,” said Taff.

“Our study is among the first to combine extensive sampling and whole genome sequencing of C. jejuni with relevant information on host ecology, movement, and social behavior,” the investigators write.

“Whether crows represent a major source of domestic animal and, ultimately, human C. jejuni infection remains uncertain, but our study indicates that data on infection prevalence and molecular characteristics of isolates alone will be insufficient for understanding C. jejuni transmission dynamics,” the investigators write. They suggest that more work is needed combining genomics, ecology, and movement and social behavior of the birds. They also note that roost sizes have increased as locations have shifted from rural to increasingly urban over the last 50 years.