I have a cousin who has carried on the family tradition and makes a living growing asparagus.

The family biz has gotten into all sorts of asparagus by-products and the farm has a large, devoted crowd of customers.

He proclaims his stuff is GMO-free.

Without going into the nuances of that statement, I said to him a few years ago while visiting, what happens if a super-great genetically engineered asparagus comes out that is beneficial to your farm, your income, and your customers?

He was too busy thinking about the present, and that’s fine.

But consumers’ attitudes can change in a heartbeat – or an outbreak.

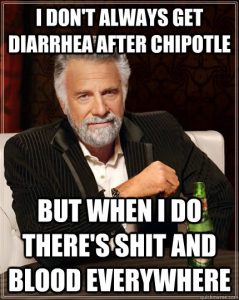

Chipotle, the purveyors of all things natural, hormone-free, sustainable, GMO-free, dolphin-free and free from whatever apparently wasn’t free from the bacteria and viruses that make people sick.

And when food folks go out on an adjective adventure to make a buck, they sometimes get burned by the realities of biology.

And the bigger the bragging, the bigger the burn.

So it’s no surprise that the depth of the damage from Chipotle Mexican Grill’s food safety issues showed up in yet another quarterly earnings report Tuesday in which net income fell 95% and missed estimates compared to the same quarter in its high-flying days a year ago.

The Denver-based company reported third-quarter net income of $7.8 million, a dramatic fall from $144.9 million a year ago. Per-share earnings totaled 27 cents, compared with $4.59 a year ago. That was well short of the $1.60 estimated by analysts polled by S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Revenue sank 14.8% year-over-year to $1 billion during the quarter despite even though the fast-casual dining chain opened 54 new restaurants with only one closing.

To me, the amazing thing is that people still spend $1 billion a year at calorie-laden faux Mexican food.

Shares of Chipotle fell 2% in after-hours trading to $397.56. The stock has fallen about 38% in the last 12 months.

Chipotle restaurants are clearly struggling from the food safety issue that sickened customers last year and forced the temporary closure of some restaurants. Comparable restaurant sales — or sales of restaurants that have been opened at least a year — tumbled 21.9%. Comparable restaurant sales are estimated to fall again “in the low single-digits” in the fourth quarter, it said.

The company’s management is more optimistic for 2017, partly due to the lower base of comparison. Comparable restaurant sales will increase “in the high single digits,” it estimated Monday. And the company will open 195 to 210 new restaurants next year, after opening more than 220 this year. Per-share earnings next year will be $10, it estimated.

“We are earning back our customers’ trust, and our research demonstrates that people are feeling better about our brand, and the quality of our food,” Steve Ells, founder, chairman and co-CEO of Chipotle, said in a statement.

“We are earning back our customers’ trust, and our research demonstrates that people are feeling better about our brand, and the quality of our food,” Steve Ells, founder, chairman and co-CEO of Chipotle, said in a statement.

Not quite.

YouGov BrandIndex, a firm that tracks a brand’s reputation, regularly asks this survey question: Is Chipotle high or low quality? Before all the bad food outbreaks, Chipotle scored a very healthy 25 (on a scale of -100 to +100) for quality. It plunged to -5 by February. It has recovered to 9 recently, but that’s still far from where it was.

Translation: Customers don’t see Chipotle as the golden brand it was before the E. coli outbreak.

Be careful, cuz.