It’s botulism week at Eurosurveillance as the on-line journal summarizes three different and recent Europe-based botulism outbreaks, which represents an alarming increase over previous years.

In an overview editorial, Cowden notes the incidence of botulism in the European Union (EU) is described elsewhere, but that from 2006 and 2008, 477 confirmed cases were notified: an .jpg) average of 119 cases per year, with a range of 104 to 132, and no discernable trend.

average of 119 cases per year, with a range of 104 to 132, and no discernable trend.

The surveillance of cases of botulism in the EU includes the three main forms of the disease but does not distinguish between them.

Food-borne botulism is caused by the ingestion of toxin produced by organisms in an anaerobic environment. It usually results from inadequately sterilised domestically canned or bottled foods.

Intestinal botulism is caused by the production in the gut of toxin by organisms which have been ingested and have proliferated. This form predominantly affects infants under a year old, often associated with the consumption of honey.

Wound botulism is caused by the production of toxin by organisms introduced into wounds. This is often associated with dirty wounds, including those following injecting drug use.

Since 2009, Eurosurveillance has published only four reports of outbreaks of food-borne botulism in Europe and only three resulted from consumption of widely distributed, commercially produced foods.

Despite only one of the four outbreaks being due to domestically prepared food, home-preserved food is generally acknowledged to be the major cause of botulism in those EU countries that have had most cases in recent years and outbreaks resulting from mass produced foods are rare.

Against this background, from September to November 2011, there were three outbreaks in three different countries in Europe. In the outbreaks which feature in this issue of Eurosurveillance, the vehicles of intoxication were demonstrated, on the basis of strong  toxicological and descriptive epidemiological evidence, to have been widely distributed, commercially produced foods.

toxicological and descriptive epidemiological evidence, to have been widely distributed, commercially produced foods.

These three outbreaks present intriguing differences and similarities.

In two outbreaks, the Finnish and the Scottish, cases were confined to single households. In France cases occurred in two household clusters.

In the French and Finnish outbreaks the vehicles included olives: olive tapenades in the French outbreak, and almond-stuffed olives in the Finnish. In the Scottish outbreak, the vehicle was korma sauce.

In all three outbreaks the vehicle of intoxication was marketed in glass jars with screw-top lids.

In the French and the Scottish outbreaks the food was produced and distributed within the country of origin. In the Finnish outbreak, the food was distributed internationally from another country, Italy.

In the Finnish and the Scottish outbreaks the food was produced in industrialized units. In the French outbreak the producer was described as an “artisanal producer” although the tapenade was commercially produced and widely distributed.

In the French and the Scottish outbreaks the toxin was type A. In the Finnish outbreak it was type B.

In two outbreaks, the Finnish and the French, defects potentially explaining the contamination were identified. In the Finnish outbreak, seals in other jars from the same batch were found to have defects, although none was found to be contaminated. In the French outbreak an improper sterilization process was identified. In the Scottish outbreak the food originated from a state-of-the-art food-production facility where intensive investigation has yet to find any shortcomings, and no post-production event has been identified which could explain the contamination.

The number of cases in all three outbreaks was surprisingly low if a production fault is assumed to have affected the production of at least a whole batch of jars.

This is particularly true of the Scottish outbreak where only one household was affected, and which could be explained by the contamination of a single jar from a batch of 1,836 jars. (1).jpeg) Likewise, the Finnish outbreak affected a single household, and could be explained by only one contaminated jar of stuffed olives, despite the batch being part of a lot of 900 imported into Finland, and the product having been exported to many countries in Europe and beyond.

Likewise, the Finnish outbreak affected a single household, and could be explained by only one contaminated jar of stuffed olives, despite the batch being part of a lot of 900 imported into Finland, and the product having been exported to many countries in Europe and beyond.

Only in the French outbreak does the contamination of more than one jar need to be hypothesized to explain the cases – and even here, contamination of only two jars could explain the cases. The size of the batch in the French outbreak was approximately 60 pots.

The other 3 outbreak write-ups are available at the urls below, and full-text, as always, on bites-l.

http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20035

http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20034

http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20036

161/11 and best before date of 10/06/2014. This type of olive is distributed under a number of different brand names but only the I DIVINI di Chicco Francesco brand is associated with this incident.

161/11 and best before date of 10/06/2014. This type of olive is distributed under a number of different brand names but only the I DIVINI di Chicco Francesco brand is associated with this incident..jpg)

But have some data.

But have some data..jpg) people in Santa Barbara.

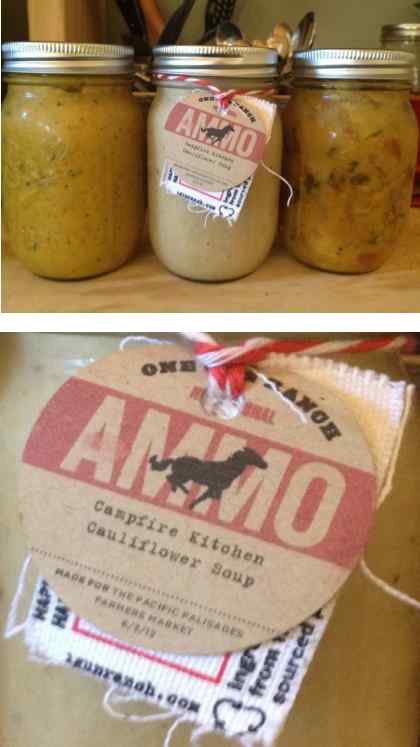

people in Santa Barbara. Sunset Blvd., Pacific Palisades, CA on May 13, 2012 and June 3, 2012.

Sunset Blvd., Pacific Palisades, CA on May 13, 2012 and June 3, 2012.

.jpeg) botulinum.Toxins produced by this bacteria may cause botulism, a life-threatening illness.

botulinum.Toxins produced by this bacteria may cause botulism, a life-threatening illness.

hosted by Poland and Ukraine between June 8 and July, 1 2012.

hosted by Poland and Ukraine between June 8 and July, 1 2012..jpg) average of 119 cases per year, with a range of 104 to 132, and no discernable trend.

average of 119 cases per year, with a range of 104 to 132, and no discernable trend. toxicological and descriptive epidemiological evidence, to have been widely distributed, commercially produced foods.

toxicological and descriptive epidemiological evidence, to have been widely distributed, commercially produced foods.(1).jpeg) Likewise, the Finnish outbreak affected a single household, and could be explained by only one contaminated jar of stuffed olives, despite the batch being part of a lot of 900 imported into Finland, and the product having been exported to many countries in Europe and beyond.

Likewise, the Finnish outbreak affected a single household, and could be explained by only one contaminated jar of stuffed olives, despite the batch being part of a lot of 900 imported into Finland, and the product having been exported to many countries in Europe and beyond.