City inspectors last year found multiple instances of the most serious type of health and sanitary code violations at nearly half of Boston’s restaurants and food service locations, according to a Globe review of municipal data.

At least two violations that can cause foodborne illness — the most serious of three levels — were discovered at more than 1,350 restaurants across Boston during 2014, according to records of inspections at every establishment in the city that serves food, including upscale dining locations, company cafeterias, takeout and fast-food restaurants, and food trucks.

Five or more of the most serious violations were discovered at more than 500 locations, or about 18 percent of all restaurants in the city, and 10 or more of the most serious violations were identified at about 200 eateries.

A violation is classified under the most serious category when inspectors observe improper practices or procedures that research has identified as the most prevalent contributing factors of foodborne illness.

Examples of such infractions include: not storing food or washing dishes at proper temperatures, employees not following hand-washing and glove-wearing protocols, and evidence that insects or rodents have been near food.

Last year, the location with the highest total of the most serious types of violation was Best Barbecue Kitchen, a small butcher shop and takeout restaurant on Beach Street in Chinatown, which racked up 70 such violations, according to city records.

That restaurant also had the highest total of violations in all categories — at 219 — last year. As of last month, Best Barbecue Kitchen had accumulated the highest number of the most serious violations: 130, dating back to 2007, when the city began posting the data online. It also had the second-highest total of violations of any type: 614.

The restaurant that had the second-highest total of the most serious violations last year was Cosi, a cafe and sandwich chain inside South Station, where 50 were found. The restaurant with the third-highest total of the most serious violations last year could be found several feet away inside South Station: Master Wok, which had 45.

Staff members at all three restaurants declined to comment last week and requests to speak with managers went unanswered.

Bob Luz, president and chief executive of the Massachusetts Restaurant Association, said the safety of customers is the top priority for restaurant owners.

“Food safety is number one for every restaurateur in the state, and obviously it’s something we consider as incredibly important,” said Luz.

Uh-huh.

consumed, where he traveled and to what animals and water sources he had been exposed. “We will try to get a clear picture of how he became ill.”

consumed, where he traveled and to what animals and water sources he had been exposed. “We will try to get a clear picture of how he became ill.” of cases of out-of-date food from the school lunch program to state prisons and a county jail.

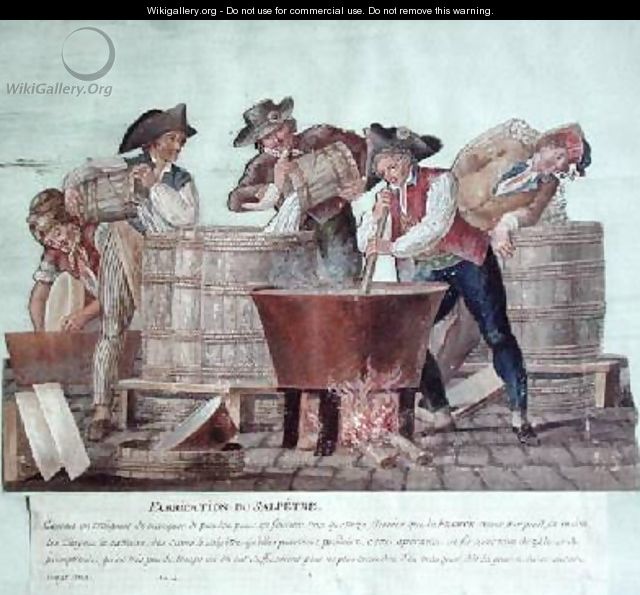

of cases of out-of-date food from the school lunch program to state prisons and a county jail. inconsistent results compared to more modern nitrate and nitrite compounds. Even so, saltpetre is still used in some food applications, such as charcuterie and the brine used to make corned beef.

inconsistent results compared to more modern nitrate and nitrite compounds. Even so, saltpetre is still used in some food applications, such as charcuterie and the brine used to make corned beef. Andrew stations in Boston.

Andrew stations in Boston..jpeg) Christmas party that it will forever be remembered as: The Party Where (Almost) Everyone Got Sick.

Christmas party that it will forever be remembered as: The Party Where (Almost) Everyone Got Sick.

At an elementary school in Billerica, the sewage smell was so strong it forced a nauseated health inspector to leave after 15 minutes. During a five-week period in Framingham, 17 mice were caught in an elementary school’s kitchen storage area. And in a Foxborough middle school, a complaint of hair in the food prompted an inquiry by a local health inspector.

At an elementary school in Billerica, the sewage smell was so strong it forced a nauseated health inspector to leave after 15 minutes. During a five-week period in Framingham, 17 mice were caught in an elementary school’s kitchen storage area. And in a Foxborough middle school, a complaint of hair in the food prompted an inquiry by a local health inspector..jpeg) In Massachusetts, school cafeteria inspections fall under the jurisdiction of local boards of health, typically small groups that are either elected or appointed, depending on the community. There are no minimum education or experience requirements to be a health inspector; candidates need only pass a state-approved performance test and a written exam, which can be taken online through the Food and Drug Administration. The state also sets no minimum qualifications for directors of local boards of health.

In Massachusetts, school cafeteria inspections fall under the jurisdiction of local boards of health, typically small groups that are either elected or appointed, depending on the community. There are no minimum education or experience requirements to be a health inspector; candidates need only pass a state-approved performance test and a written exam, which can be taken online through the Food and Drug Administration. The state also sets no minimum qualifications for directors of local boards of health.