Christopher Mele of the New York Times writes the former chief executive of Blue Bell Creameries was charged with conspiracy in connection with his repeated efforts to cover up what became a deadly outbreak of listeria in some of the company’s products in 2015.

In addition, the company pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of distributing adulterated ice cream products and agreed to pay a total of $19.4 million in fines, forfeitures and civil payments — the second-largest amount ever paid to resolve a food safety case, officials said. (Chipotle Mexican Grill last month agreed to pay a $25 million fine related to charges stemming from more than 1,100 cases of foodborne illnesses.)

In addition, the company pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of distributing adulterated ice cream products and agreed to pay a total of $19.4 million in fines, forfeitures and civil payments — the second-largest amount ever paid to resolve a food safety case, officials said. (Chipotle Mexican Grill last month agreed to pay a $25 million fine related to charges stemming from more than 1,100 cases of foodborne illnesses.)

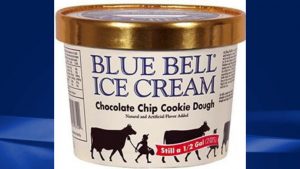

Prosecutors charged that Blue Bell, which is based in Brenham, Texas, about 75 miles northwest of Houston, distributed ice cream products that were manufactured under unsanitary conditions and contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes.

Three deaths and 10 hospitalizations across four states were tied to the 2015 outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported.

The former chief executive, Paul Kruse, who was also Blue Bell’s president, directed a scheme to cover up the discovery that some products tested positive for listeria, according to court papers. He directed a company employee to stop a testing program for listeria even after two samples sent to a lab came back positive, court records said.

Further, Mr. Kruse did not order the recall of the affected products despite Blue Bell filing a report to federal regulators that it was recalling them “as quickly as possible,” court papers said.

For a period of more than two months in 2015, Mr. Kruse learned from state and federal officials as well as third-party labs that test samples of at least seven company ice cream products made at two different plants had tested positive for listeria, court papers said.

Yet, prosecutors contend, he repeatedly minimized, ignored or tried to cover up the problem products, which included Blue Bell Great Divide Bar and Chocolate Chip Country Cookie, despite concerns raised by company employees and customers, including a Kansas hospital and a Florida school.

For instance, he directed employees to tell customers that there had been an unspecified issue with a manufacturing machine rather than that samples of the products had tested positive for listeria, officials said.

On Feb. 17, 2015, Mr. Kruse rejected sending a draft news release about two products that tested positive for listeria, the withdrawal of those products and a warning to consumers about the potential health consequences. Mr. Kruse instructed the company executive who brought him the proposed release that it was unnecessary, court papers said.

Chris Flood, a lawyer for Mr. Kruse, said on Friday that his client was innocent of the charges.