Compliance Documents

Q1. Where can I find information on the new “mechanically tenderized beef products regulation per 9 CFR 317.2(e)(3)?

Information on “mechanically tenderized beef products” is available from the following locations:

- Docket No. FSIS-2008-0017 | PDF

- FSIS Compliance Guideline for Validating Cooking Instructions for Mechanically Tenderized Beef Products

Q2. Under this final rule, will the product need to be labeled with the specific method of mechanical tenderization used to prepare the product?

No, the label need not include the specific type of mechanical tenderization used. To provide flexibility, FSIS is allowing the phrase ‘‘mechanically tenderized’’ to be used as the descriptive designation on any type of mechanically tenderized product. In addition, in lieu of “mechanically tenderized,” such product may be labeled as ‘‘needle tenderized’’ or ‘‘blade tenderized,’’ as applicable.

No, the label need not include the specific type of mechanical tenderization used. To provide flexibility, FSIS is allowing the phrase ‘‘mechanically tenderized’’ to be used as the descriptive designation on any type of mechanically tenderized product. In addition, in lieu of “mechanically tenderized,” such product may be labeled as ‘‘needle tenderized’’ or ‘‘blade tenderized,’’ as applicable.

Q3. Can “needle injected” be used as the descriptive designation on the labels of raw or partially cooked beef products that have been mechanically tenderized?

No, needle injected may not be used as the descriptive designation. The terms “needle tenderized” or “mechanically tenderized” must be used as the descriptive designation for needle tenderized raw or partially cooked beef products and the terms “mechanically tenderized” or “blade tenderized” must be used as the descriptive designation for raw or partially cooked blade tenderized beef products.

Q4. Are the descriptive designations “mechanically tenderized,” “blade tenderized,” or “needle tenderized” only required on raw or partially cooked beef products?

Yes, unless the product is destined to be fully cooked or to receive another full lethality

treatment at an official establishment, such product must be labeled accordingly.

Q5. Do the new labeling requirements apply to mechanically tenderized pork, lamb, or goat products?

No. The rule applies only to raw or partially cooked beef products that have been mechanically tenderized.

Q6. Can establishments put both mechanically tenderized beef products and non- mechanically tenderized beef products in the same immediate container and label it with the descriptive designation “mechanically tenderized?”

No. To label product as “mechanically tenderized” when it was not would be false and misleading.

Q7. If we sell mechanically tenderized raw or partially cooked beef or veal products in protective coverings, must the protective coverings meet the mechanical tenderization labeling requirements when the immediate container of this product is labeled “For Institutional Use Only?”

Q7. If we sell mechanically tenderized raw or partially cooked beef or veal products in protective coverings, must the protective coverings meet the mechanical tenderization labeling requirements when the immediate container of this product is labeled “For Institutional Use Only?”

No. Under 9 CFR 317.1(a)(1), protective coverings should not bear any mandatory labeling information.” In this case, the immediate container, which also serves as the shipping container, is required to be labeled with the descriptive designation and bear validated cooking instructions and all other applicable labeling features.

Q8. Is beef cubed steak is subject to the new labeling requirements?

No, this regulation will not apply to raw or partially cooked beef products that have been cubed. The regulation is specific to needle and blade tenderized beef products. FSIS stated in the final rule:

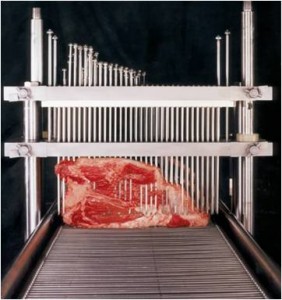

The descriptive designation will only apply to raw or partially cooked beef products that have been needle tenderized or blade-tenderized, including beef products injected with marinade or solution. Other tenderization methods, such as pounding and cubing, change the appearance of the product, putting consumers on notice that the product is not intact. Moreover, most establishments already label cubed products as such. (80 FR 28157)

Q9. Must the labels for raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products be submitted to the FSIS Labeling and Program Delivery Staff (LPDS) for approval?

No. The descriptive designations, “mechanically tenderized,” “blade tenderized,” and “needle tenderized” are not considered special statements or claims under 9 CFR 412.1(c). Therefore, as stated in the final rule, simply adding the descriptive designation and validated cooking instructions to a label would not require LPDS approval, given the label is otherwise in accordance with FSIS’s regulations.

Q10. Do the new labeling requirements apply to raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products that are produced at establishments that use a validated intervention during the production of such products?

Yes, the new labeling requirements would apply to products treated with a validated antimicrobial intervention, unless the establishment applies a lethality treatment that achieves a 5-log reduction in pathogens. Mechanically tenderized beef product treated at an official establishment with an intervention or process, including HPP, that has been validated to achieve at least a 5-log reduction for Salmonella and Shiga Toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) organisms (including E. coli 0157:H7) would not be subject to the requirements in this final rule because it has received a full lethality treatment. (See 80 FR 28153)

Q11. Do the new labeling requirements apply to mechanically tenderized beef products labeled or prepared at retail stores?

Yes, the new labeling requirements would apply to raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products produced, packaged, and labeled at a retail store.

Cooking Instructions

Q12. Is there compliance guidance available on validating cooking instructions for mechanically tenderized beef products?

Yes, at:

FSIS Compliance Guideline for Validating Cooking Instructions for Mechanically Tenderized Beef Products

Q13. Where can I find scientific studies on validated cooking instructions?

Attachment 1 of the above FSIS Compliance Guideline for Validating Cooking Instructions for Mechanically Tenderized Beef Products contains a summary of published scientific support for cooking instructions.

Q14. Do the new labeling requirements apply to raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products that are too thin to practically measure their internal temperature using a food thermometer?

No, the new labeling requirements do not apply to raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized (including through injection with a solution) beef products that are too thin to measure their internal temperature using a food thermometer, such as beef bacon or carne asada. FSIS does not intend to enforce the requirements for these products because they are customarily prepared in a manner that is sufficient to destroy pathogenic bacteria.

Note that the thickness of many food thermometers used by consumers is approximately 1/8,” making it difficult to measure the end product temperature of products 1/8” thick or less through use of a thermometer.

Q15. Where on the label of raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products can the validated cooking instructions appear?

Validated cooking instructions must appear on the immediate containers of all raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef products destined for household consumers, hotels, restaurants, or similar institutions. These instructions can appear anywhere on the product label.

Mechanically Tenderized Beef With Solutions

Q16. Must the label of a raw or partially cooked mechanically tenderized beef product that contains added solution also declare the percentage of added solution?

Yes. However, there are different options for declaring the total amount of solution added. See 9 CFR 317.2(e)(2).

Q17. Do the new labeling requirements apply to raw or partially cooked beef products that have been marinated in a tumbler or vacuum tumbled?

The rule only applies to raw or partially cooked beef products that have been mechanically tenderized by needle or blade. This rule does not apply to other processes, such as tumbling or vacuum tumbling, unless the product is also mechanically tenderized by needle or blade.

.jpeg) produced in the U.S. each month, according to a federal study, but it’s not required to be labeled.

produced in the U.S. each month, according to a federal study, but it’s not required to be labeled. infected. It was a real mess: in Angers there was only one pharmacy that had the vaccination I needed.”

infected. It was a real mess: in Angers there was only one pharmacy that had the vaccination I needed.”.jpg) one is saying how common.

one is saying how common. ground up – the outside, which can be laden with poop, is on the inside. With steaks, the thought has been that searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside?

ground up – the outside, which can be laden with poop, is on the inside. With steaks, the thought has been that searing on the outside will take care of any poop bugs like E. coli and the inside is clean. But what if needles pushed the E. coli on the outside of the steak to the inside? That was 1999. I don’t see any such intact or non-intact label when I go to the grocery store. Restaurants remain a faith-based food safety institution. And the issue has rarely risen to the level of public discussion.

That was 1999. I don’t see any such intact or non-intact label when I go to the grocery store. Restaurants remain a faith-based food safety institution. And the issue has rarely risen to the level of public discussion.