My friend, Wal-Mart Frank, has written a follow-up to his 2008 book, Food Safety Culture. This is from the introduction:

As a food safety professional, getting others to comply with what you are asking them to do is critical, but it is not easy. In fact, it can be very hard to change other’s behaviors. And if you are like most food safety professionals, you have probably received little or no formal training on how to influence or change people’s behaviors.

As a food safety professional, getting others to comply with what you are asking them to do is critical, but it is not easy. In fact, it can be very hard to change other’s behaviors. And if you are like most food safety professionals, you have probably received little or no formal training on how to influence or change people’s behaviors.

But what if I told you that simple and proven behavioral science techniques exist, and, if applied strategically, can significantly enhance your ability to influence others and improve food safety. Would you be interested?

The need to better integrate the important relationship between behavioral science and food safety is what motivated me to write this book, Food Safety = Behavior, 30 Proven Techniques to Enhance Employee Compliance.

When it comes to food safety, people’s attitudes, choices, and behaviors are some of the most important factors that influence the overall safety of our food supply. Real-world examples of how these human factors influence the safety of our food range from whether or not a food worker will decide to wash his or her hands before working with food to the methods a health department utilizes while attempting to improve food safety compliance within a community to the decisions a food manufacturer’s management team will make on how to control a food safety hazard. They all involve human elements.

If concepts related to human and social behavior are so important to advancing food safety, why are they noticeably absent or lacking in the food safety profession today? Although there are probably several good reasons, I believe it is largely due to the fact that, historically, food safety professionals have not received adequate training or education in the behavioral sciences. Therefore, there are numerous food safety professionals who approach their jobs with an over-reliance on the food sciences alone. They rely too heavily, in my opinion, on traditional food safety approaches based on training, inspections, and testing.

If concepts related to human and social behavior are so important to advancing food safety, why are they noticeably absent or lacking in the food safety profession today? Although there are probably several good reasons, I believe it is largely due to the fact that, historically, food safety professionals have not received adequate training or education in the behavioral sciences. Therefore, there are numerous food safety professionals who approach their jobs with an over-reliance on the food sciences alone. They rely too heavily, in my opinion, on traditional food safety approaches based on training, inspections, and testing.

Despite the fact that thousands of employees have been trained in food safety around the world, millions of dollars have been spent globally on food safety research, and countless inspections and tests have been performed at home and abroad, food safety remains a significant public health challenge. Why is that? The answer to this question reminds me of a quote by the late psychologist Abraham Maslow, who said, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.” To improve food safety, we have to realize that it’s more than just food science; it’s the behavioral sciences too.

Think about it. If you are trying to improve the food safety performance of an organization, industry, or region of the world, what you are really trying to do is change peoples’ behaviors. Simply put, food safety equals behavior. This truth is the fundamental premise upon which this entire book is based.

How does one effectively influence the behaviors of a worker, a social group, a community, or an organization?

While it is not easy, fortunately, there is good news for today’s more progressive, behavior-based food safety professional. Over the past 50 years, an incredible amount of research has been done in the behavioral and social sciences that have provided valuable insights into the thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors of humans. Applying these studies’ conclusions to our field has the potential to dramatically change our preventative food safety approaches, enhance employee compliance, and, most importantly, save lives.

While it is not easy, fortunately, there is good news for today’s more progressive, behavior-based food safety professional. Over the past 50 years, an incredible amount of research has been done in the behavioral and social sciences that have provided valuable insights into the thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors of humans. Applying these studies’ conclusions to our field has the potential to dramatically change our preventative food safety approaches, enhance employee compliance, and, most importantly, save lives.

One of the most exciting aspects of behavioral science research is that its results are often of simple and practical use to numerous professions, including ours – food safety. Generally, the principles learned through behavioral science research require little technical or scientific equipment to implement. They usually do not require large expenses. What is required, however, is an understanding of the research data and the ability to infer how the research might be used to solve a problem in your area of concern.

In this book, Food Safety = Behavior, I’ve decided to collect some of the most interesting behavioral science studies I’ve reviewed over the past few years, which I believe might have relevance to food safety. I’ve assembled them into one easy-to- use book with suggested applications in how they might be used to advance food safety.

To get the most out of this book, at the end of each chapter, I strongly encourage you to spend a few minutes thinking about the behavioral science principle you have just read, what it means to food safety, and how you might apply that principle in your own organization (or in your role) to improve food safety. For those in academic set- tings, you might also want to make a list of potential questions for further research.

In summary, this book is devoted to introducing you to new ideas and concepts that have not been thoroughly reviewed, researched, and, more importantly, applied in the field of food safety. It is my attempt to arm you with new behavioral science tools to further reduce food safety risks in certain parts of the food system and world. I am convinced that we need to adopt new, out-of-the-box thinking that is more heavily focused on influencing and changing human behavior in order to accomplish this goal.

In summary, this book is devoted to introducing you to new ideas and concepts that have not been thoroughly reviewed, researched, and, more importantly, applied in the field of food safety. It is my attempt to arm you with new behavioral science tools to further reduce food safety risks in certain parts of the food system and world. I am convinced that we need to adopt new, out-of-the-box thinking that is more heavily focused on influencing and changing human behavior in order to accomplish this goal.

It is my hope that by simply reading this book, you pick up a few good ideas, tips, or approaches that can help you improve the food safety performance of your organization or area of responsibility. If you do, I will consider this book a success.

In closing, thanks for taking the time to read Food Safety = Behavior and, more importantly, for all that you are doing to advance food safety, so that people worldwide can live better.

(2).jpg) imagination.

imagination..jpeg) of 43 cross-contamination events per household. They concluded Thermy had not been successful.

of 43 cross-contamination events per household. They concluded Thermy had not been successful.(1).jpg)

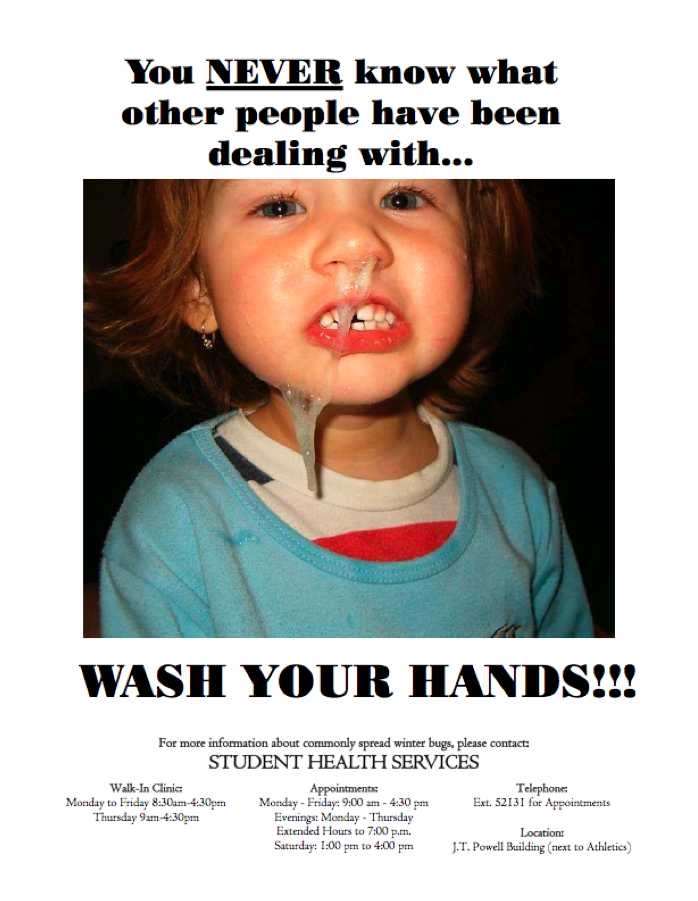

far less effective than ads that also "disgust" consumers into taking the action. The best way to elicit disgust: Display totally gross images (see our

far less effective than ads that also "disgust" consumers into taking the action. The best way to elicit disgust: Display totally gross images (see our  ad with the same written copy, but which replaced the photo of the pock-marked young man with one of a coffin.

ad with the same written copy, but which replaced the photo of the pock-marked young man with one of a coffin. when disgust was far from the mainstream.

when disgust was far from the mainstream. because they often present dangers to public health.

because they often present dangers to public health.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans.

behavior is essential to prevent the spread of all the major current and recent infectious diseases which present a threat to humans. better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today.

better. Practically, disgust can be harnessed to combat the behavioural causes of infectious and chronic disease such as diarrhoeal disease, pandemic flu and smoking. Disgust is also a source of much human suffering; it plays an underappreciated role in anxieties and phobias such as obsessive compulsive disorder, social phobia and post-traumatic stress syndromes; it is a hidden cost of many occupations such as caring for the sick and dealing with wastes, and self-directed disgust afflicts the lives of many, such as the obese and fistula patients. Disgust is used and abused in society, being both a force for social cohesion and a cause of prejudice and stigmatization of out-groups. This paper argues that a better understanding of disgust, using the new synthesis, offers practical lessons that can enhance human flourishing. Disgust also provides a model system for the study of emotion, one of the most important issues facing the brain and behavioural sciences today.