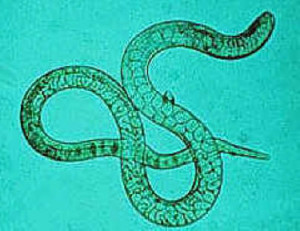

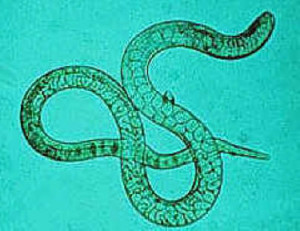

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports that trichinellosis is a parasitic disease caused by nematodes in the genus Trichinella, which are among the most widespread zoonotic pathogens globally. Infection occurs following consumption of raw or undercooked meat infected with Trichinella larvae.

Clinical manifestations of the disease range from asymptomatic infection to fatal disease; the common signs and symptoms include eosinophilia, fever, periorbital edema, and myalgia. Trichinellosis surveillance has documented a steady decline in the reported incidence of the disease in the United States. In recent years, proportionally fewer cases have been associated with consumption of commercial pork products, and more are associated with meat from wild game such as bear.

Clinical manifestations of the disease range from asymptomatic infection to fatal disease; the common signs and symptoms include eosinophilia, fever, periorbital edema, and myalgia. Trichinellosis surveillance has documented a steady decline in the reported incidence of the disease in the United States. In recent years, proportionally fewer cases have been associated with consumption of commercial pork products, and more are associated with meat from wild game such as bear.

Period Covered: 2008–2012.

Description of System: Trichinellosis has been a nationally notifiable disease in the United States since 1966 and is reportable in 48 states, New York City, and the District of Columbia. The purpose of national surveillance is to estimate incidence of infection, detect outbreaks, and guide prevention efforts. Cases are defined by clinical characteristics and the results of laboratory testing for evidence of Trichinella infection. Food exposure histories are obtained at the local level either at the point of care or through health department interview. States notify CDC of cases electronically through the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (available at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss). In addition, states are asked to submit a standardized supplementary case report form that captures the clinical and epidemiologic information needed to meet the surveillance case definition. Reported cases are summarized weekly and annually in MMWR.

Results: During 2008–2012, a total of 90 cases of trichinellosis were reported to CDC from 24 states and the District of Columbia. Six (7%) cases were excluded from analysis because a supplementary case report form was not submitted or the case did not meet the case definition. A total of 84 confirmed trichinellosis cases, including five outbreaks that comprised 40 cases, were analyzed and included in this report. During 2008–2012, the mean annual incidence of trichinellosis in the United States was 0.1 cases per 1 million population, with a median of 15 cases per year. Pork products were associated with 22 (26%) cases, including 10 (45%) that were linked with commercial pork products, six (27%) that were linked with wild boar, and one (5%) that was linked with home-raised swine; five (23%) were unspecified. Meats other than pork were associated with 45 (54%) cases, including 41 (91%) that were linked with bear meat, two (4%) that were linked with deer meat, and two (4%) that were linked with ground beef. The source for 17 (20%) cases was unknown. Of the 51 patients for whom information was reported on the manner in which the meat product was cooked, 24 (47%) reported eating raw or undercooked meat.

Interpretation: The risk for Trichinella infection associated with commercial pork has decreased substantially in the United States since the 1940s, when data collection on trichinellosis cases first began. However, the continued identification of cases related to both pork and nonpork sources indicates that public education about trichinellosis and the dangers of consuming raw or undercooked meat still is needed.

Public Health Actions: Changes in domestic pork production and public health education regarding the safe preparation of pork have contributed to the reduction in the incidence of trichinellosis in the United States; however, consumption of wild game meat such as bear continues to be an important source of infection. Hunters and consumers of wild game meat should be educated about the risk associated with consumption of raw or undercooked meat.

He was part of a group of 3 French people having recently travelled in East Greenland. Between, 13 and 16 Feb 2016, they each had consumed around 200 g of polar bear (_Ursus maritimus_) meat. The polar bear meat had been cut into 1 cm thick slices and then fried for several minutes, but was still pink when eaten.

He was part of a group of 3 French people having recently travelled in East Greenland. Between, 13 and 16 Feb 2016, they each had consumed around 200 g of polar bear (_Ursus maritimus_) meat. The polar bear meat had been cut into 1 cm thick slices and then fried for several minutes, but was still pink when eaten.