CBC News reports British Columbia has recorded its first case this year of someone being sickened by eating raw oysters contaminated with Vibrio bacteria.

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) said the illness was reported June 30 in the Vancouver area.

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) said the illness was reported June 30 in the Vancouver area.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteria grow in seawater and can end up in shellfish like oysters and clams. When water temperatures rise in the summer, the accumulations of the naturally occurring bacteria increase to the point that eating undercooked shellfish can give people nausea, fever and diarrhea.

Last year’s outbreak of the Vibrio-caused illness was the biggest in Canadian history and sickened at least 73 British Columbians. Sixty of the illnesses were due to eating contaminated raw or undercooked B.C. oysters in restaurants. The other 13 illnesses were traced to exposure to seawater with high levels of the bacteria.

At the height of the outbreak last summer, Vancouver Coastal Health ordered restaurants not to serve raw oysters harvested from B.C. waters and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency issued a food recall for B.C. oysters.

“Eating raw shellfish increases your risk of Vibrio and other infections,” said Dr. Eleni Galanis, epidemiologist at the BCCDC, in a release.

“It’s best to eat them cooked, but if you choose to eat raw shellfish like oysters, then understand the risks and take steps to reduce your likelihood of illness.”

Meanwhile, Florida health officials have reported 13 Vibrio vulnificus cases as of July 5, including four fatalities thus far in 2016.

Last year, Florida saw 45 cases and 14 deaths, the most since 2003.

Healthy individuals typically develop a mild disease; however, Vibrio vulnificus infections can be a serious concern for people who have weakened immune systems, particularly those with chronic liver disease.

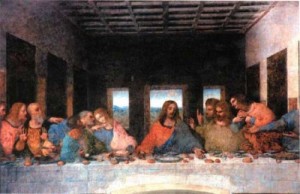

![Oyster-Vancouver, B.C.- 07/05/07- Joe Fortes Oyster Specialist Oyster Bob Skinner samples a Fanny Bay oyster at the restuarant. Vancouver Coastal Health now requires restaurants to inform their patrons of the dangers of eating raw shellfish. (Richard Lam/Vancouver Sun) [PNG Merlin Archive]](https://barfblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/raw.oyster.jpg)

So don’t be a drunk and eat raw.

I BBQ them, and prefer scallops on the half-shell.

In other Virbrio news, UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers have uncovered a mechanism that a type of pathogenic bacteria found in shellfish use to sense when they are in the human gut, where they release toxins that cause food poisoning.

The researchers studied Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a globally spread, Gram-negative bacterium that contaminates shellfish in warm saltwater during the summer. The bacterium thrives in coastal waters and is the world’s leading cause of acute gastroenteritis.

“During recent years, rising temperatures in the ocean have contributed to this pathogen’s worldwide dissemination,” said Dr. Kim Orth, Professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry at UT Southwestern and senior author of the study, published today in the online journal eLife.

About a dozen Vibrio species cause infection in humans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus is one of the three most common culprits. Vibrio infections cause an estimated 80,000 illnesses and 100 deaths in the United States every year.

The study found that two proteins made by Vibrio parahaemolyticus work together to detect and capture bile salts in the intestines of people who eat raw or undercooked seafood containing the bacteria.

“When a person eats, acids in the stomach help break down the meal, and bile salts in the intestine aid in the solubilization of fatty food. When humans eat raw or undercooked shellfish contaminated with Vibrio parahaemolyticus, the bacteria use those same bile salts as a signal to release toxins,” said Dr. Orth, also an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), holder of the Earl A. Forsythe Chair in Biomedical Science, and a W.W. Caruth, Jr. Scholar in Biomedical Research. Dr. Orth studies the strategies that bacterial pathogens use to outsmart their host cells.

Evidence is increasing that several bacterial pathogens that cause gastrointestinal illness, including the extremely toxic Vibrio cholerae, sense bile salts. But until now, the mechanism that those pathogens use for doing this has remained unknown, Dr. Orth said. In previous studies, only one bacterial gene had been implicated in receiving and transmitting the gut-sensing signal, Dr. Orth said.

“We discovered that not one, but two genes are required for Vibrio to receive the bile salt signal. These genes encode two proteins that form a complex on the surface of the bacterial membrane. Using X-ray crystallography, we found that these proteins create a barrel-like structure that binds bile salts and receives the signal to tell the bacterial cell to start making toxins,” she said.

Future experiments will aim to understand how binding of bile salt by this protein complex induces the release of toxins.

“Ultimately, we want to understand how other pathogenic bacteria sense environmental cues to produce toxins. With this knowledge, we might be able to design pharmaceuticals that could prevent toxin production, and ultimately avoid the damaging effects of infections,” she said.

The receptor pair could possibly act as a model to discover sensors in other bacteria where pharmaceuticals might be more applicable, Dr. Orth said, adding “we are in the early stages of this research.”

Co-lead authors were graduate student Peng Li and research scientist Dr. Giomar Rivera-Cancel, both in Molecular Biology. Other contributing authors included Dr. Lisa Kinch, an HHMI bioinformatics specialist; Dr. Dor Salomon, postdoctoral researcher; Dr. Diana Tomchick, Professor of Biophysics and Biochemistry and Director of the Structural Biology Core Facility; and Dr. Nick Grishin, Professor of Biophysics and Biochemistry, an HHMI Investigator, and a Virginia Murchison Linthicum Scholar in Biomedical Research.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Welch Foundation, the Department of Energy, and the HHMI.

And finally, bacterial infections from various organisms including Vibrio sp. pose a serious hazard to humans in many forms from clinical infection to affecting the yield of agriculture and aquaculture via infection of livestock. Vibrio sp. is one of the main foodborne pathogens causing human infection and is also a common cause of losses in the aquaculture industry. Prophylactic and therapeutic usage of antibiotics has become the mainstay of managing this problem, however this in turn led to the emergence of multidrug resistant strains of bacteria in the environment; which has raised awareness of the critical need for alternative non antibiotic based methods of preventing and treating bacterial infections. Bacteriophages – viruses that infect and result in the death of bacteria – are currently of great interest as a highly viable alternative to antibiotics. This article provides an insight into bacteriophage application in controlling Vibrio species as well underlining the advantages and drawbacks of phage therapy.

Insights into bacteriophage application in controlling Vibrio species

Front. Microbiol. | doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01114

http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01114/abstract

Vengadesh Letchumanan, Kok Gan Chan, Priyia Pusparajah, Surasak Saokaew, Acharaporn Duangjai, Bey Hing Goh, Nurul-Syakima Ab Mutalib and Learn-Han Lee

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control says about 40 cases of acute gastrointestinal illness have been connected to the consumption of raw oysters since March. Testing has confirmed some of the cases were norovirus.

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control says about 40 cases of acute gastrointestinal illness have been connected to the consumption of raw oysters since March. Testing has confirmed some of the cases were norovirus.

![Oyster-Vancouver, B.C.- 07/05/07- Joe Fortes Oyster Specialist Oyster Bob Skinner samples a Fanny Bay oyster at the restuarant. Vancouver Coastal Health now requires restaurants to inform their patrons of the dangers of eating raw shellfish. (Richard Lam/Vancouver Sun) [PNG Merlin Archive]](https://barfblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/raw.oyster.jpg)

![Oyster-Vancouver, B.C.- 07/05/07- Joe Fortes Oyster Specialist Oyster Bob Skinner samples a Fanny Bay oyster at the restuarant. Vancouver Coastal Health now requires restaurants to inform their patrons of the dangers of eating raw shellfish. (Richard Lam/Vancouver Sun) [PNG Merlin Archive]](https://barfblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/raw.oyster1.jpg)