On June 12, 1996, Ontario’s chief medical officer, Dr. Richard Schabas, issued a public health advisory on the presumed link between  consumption of California strawberries and an outbreak of diarrheal illness among some 40 people in the Metro Toronto area. The announcement followed a similar statement from the Department of Health and Human Services in Houston, Texas, who were investigating a cluster of 18 cases of Cyclospora illness among oil executives.

consumption of California strawberries and an outbreak of diarrheal illness among some 40 people in the Metro Toronto area. The announcement followed a similar statement from the Department of Health and Human Services in Houston, Texas, who were investigating a cluster of 18 cases of Cyclospora illness among oil executives.

Dr. Schabas advised consumers to wash California berries "very carefully" before eating them, and recommended that people with compromised immune systems avoid them entirely. He also stated that Ontario strawberries, which were just beginning to be harvested, were safe for consumption. Almost immediately, people in Ontario stopped buying strawberries. Two supermarket chains took California berries off their shelves, in response to pressure from consumers. The market collapsed so thoroughly that newspapers reported truck drivers headed for Toronto with loads of berries being directed, by telephone, to other markets.

However, by June 20, 1996, discrepancies began to appear in the link between California strawberries and illness caused by the parasite, Cyclospora, even though the number of reported illnesses continued to increase across North America. Texas health officials strengthened their assertion that California strawberries were the cause of the outbreak, while scientists at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said there were not yet ready to identify a food vehicle for the outbreak. On June 27, 1996, the New York City Health Department became the first in North America to publicly state that raspberries were also suspected in the outbreak of Cyclospora.

By July 18, 1996, the CDC declared that raspberries from Guatemala — which had been sprayed with pesticides mixed with water that could have been contaminated with human sewage containing Cyclospora — were the likely source of the Cyclospora outbreak, which ultimately sickened about .jpg) 1,000 people across North America. Guatemalan health authorities and producers have vigorously refuted the charges. The California Strawberry Commission estimates it lost $15 million to $20 million in reduced strawberry sales.

1,000 people across North America. Guatemalan health authorities and producers have vigorously refuted the charges. The California Strawberry Commission estimates it lost $15 million to $20 million in reduced strawberry sales.

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a recently characterised coccidian parasite; the first known cases of infection in humans were diagnosed in 1977. Before 1996, only three outbreaks of Cyclospora infection had been reported in the United States. Cyclospora is normally associated with warm, Latin American countries with poor sanitation.

One reason for the large amount of uncertainty in the 1996 Cyclospora outbreak is the lack of effective testing procedures for this organism. To date, Cyclospora oocysts have not been found on any strawberries, raspberries or other fruit, either from North America or Guatemala. That does not mean that cyclospora was absent; it means the tests are unreliable and somewhat meaningless. FDA, CDC and others are developing standardized methods for such testing and are currently evaluating their sensitivity.

The initial, and subsequent, links between Cyclospora and strawberries or raspberries were therefore based on epidemiology, a statistical association between consumption of a particular food and the onset of disease. For example, the Toronto outbreak was first identified because some 35 guests attending a May 11, 1996 wedding reception developed the same severe, intestinal illness, seven to 10 days after the wedding, and subsequently tested positive for cyclospora. Based on interviews with those stricken, health authorities in Toronto and Texas concluded that California strawberries were the most likely source. However, attempts to remember exactly what one ate two weeks earlier is an extremely difficult task; and larger foods, like strawberries, are recalled more frequently than smaller foods, like raspberries. Ontario strawberries were never implicated in the outbreak.

Once epidemiology identifies a probable link, health officials have to decide whether it makes sense to warn the public. In retrospect, the decision seems straightforward, but there are several possibilities that must be weighed at the time. If the Ontario Ministry of Health decided to warn people that eating imported strawberries might be connected to Cyclospora infection, two outcomes were possible: if it turned out that strawberries are implicated, the ministry has made a smart decision, warning people against something that could hurt them; if strawberries were not implicated, then the ministry has made a bad decision with the result that strawberry growers and sellers will lose money and people will stop eating something that is good for them. If the ministry decides not to warn people, another two outcomes are possible: if strawberries were implicated, then the ministry has made a bad decision and people may get a parasitic infection they would have avoided had they been given the information (lawsuits usually follow); if strawberries were definitely not .jpg) implicated then nothing happens, the industry does not suffer and the ministry does not get in trouble for not telling people. Research is currently being undertaken to develop more rigorous, scientifically-tested guidelines for informing the public of uncertain risks.

implicated then nothing happens, the industry does not suffer and the ministry does not get in trouble for not telling people. Research is currently being undertaken to develop more rigorous, scientifically-tested guidelines for informing the public of uncertain risks.

But in Sarnia (Ontario, Canada) they got a lot of sick people who attended the Big Sisters of Sarnia-Lambton Chef’s Challenge on May 12, 2010.

The health department has completed interviews with over 270 people who attended the event. Of those people interviewed, 193 have reported being ill with symptoms consistent with cyclospora infection. There are currently 40 laboratory confirmed cases.

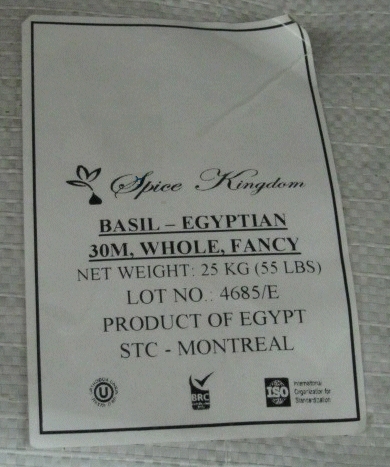

brand dried Egyptian Basil described below because the product may be contaminated with Salmonella.

brand dried Egyptian Basil described below because the product may be contaminated with Salmonella.

.png) product has been withdrawn from the market. No further cases have been reported since 25 October.

product has been withdrawn from the market. No further cases have been reported since 25 October. served at all three events was salad mix, fresh basil and cherry tomatoes.

served at all three events was salad mix, fresh basil and cherry tomatoes..jpg)

salmonella. These products have been distributed in Ontario.

salmonella. These products have been distributed in Ontario. corporate luncheon on June 26 at the company’s branch in Fairfax, Virginia, had developed gastrointestinal illness (Centres for Disease Control, 1997). On July 11, the health department was notified that a stool specimen from one of the employees who attended the luncheon was positive for Cyclospora oocysts. Many others tested positive. It was subsequently revealed in a July 19, 1997, Washington Post story citing local health department officials that basil and pesto from four Sutton Place Gourmet stores around Washington D.C. was the source of cyclospora for 126 people who attended at least 19 separate events where Sutton Place basil products were served, from small dinner parties and baby showers to corporate gatherings (Masters, 1997a). Of the 126, 30 members of the National Symphony Orchestra became sick after they ate box lunches provided by Sutton Place at Wolf Trap Farm Park.

corporate luncheon on June 26 at the company’s branch in Fairfax, Virginia, had developed gastrointestinal illness (Centres for Disease Control, 1997). On July 11, the health department was notified that a stool specimen from one of the employees who attended the luncheon was positive for Cyclospora oocysts. Many others tested positive. It was subsequently revealed in a July 19, 1997, Washington Post story citing local health department officials that basil and pesto from four Sutton Place Gourmet stores around Washington D.C. was the source of cyclospora for 126 people who attended at least 19 separate events where Sutton Place basil products were served, from small dinner parties and baby showers to corporate gatherings (Masters, 1997a). Of the 126, 30 members of the National Symphony Orchestra became sick after they ate box lunches provided by Sutton Place at Wolf Trap Farm Park. cool pesto crunch (it was a chef showoff fundraiser), but can’t identify the ingredient, I’m leaning towards the basil.

cool pesto crunch (it was a chef showoff fundraiser), but can’t identify the ingredient, I’m leaning towards the basil. consumption of California strawberries and an outbreak of diarrheal illness among some 40 people in the Metro Toronto area. The announcement followed a similar statement from the Department of Health and Human Services in Houston, Texas, who were investigating a cluster of 18 cases of Cyclospora illness among oil executives.

consumption of California strawberries and an outbreak of diarrheal illness among some 40 people in the Metro Toronto area. The announcement followed a similar statement from the Department of Health and Human Services in Houston, Texas, who were investigating a cluster of 18 cases of Cyclospora illness among oil executives..jpg) 1,000 people across North America. Guatemalan health authorities and producers have vigorously refuted the charges. The California Strawberry Commission estimates it lost $15 million to $20 million in reduced strawberry sales.

1,000 people across North America. Guatemalan health authorities and producers have vigorously refuted the charges. The California Strawberry Commission estimates it lost $15 million to $20 million in reduced strawberry sales..jpg) implicated then nothing happens, the industry does not suffer and the ministry does not get in trouble for not telling people. Research is currently being undertaken to develop more rigorous, scientifically-tested guidelines for informing the public of uncertain risks.

implicated then nothing happens, the industry does not suffer and the ministry does not get in trouble for not telling people. Research is currently being undertaken to develop more rigorous, scientifically-tested guidelines for informing the public of uncertain risks..jpg) ranging from basil to sage — federal regulators met last week with the spice industry to figure out ways to make the supply safer.

ranging from basil to sage — federal regulators met last week with the spice industry to figure out ways to make the supply safer. Last year, with Amy’s guidance, was the first year I really started cooking with fresh herbs. Basil and tomato (and formerly cheese, right), fresh pesto, bruschetta, it’s all good.

Last year, with Amy’s guidance, was the first year I really started cooking with fresh herbs. Basil and tomato (and formerly cheese, right), fresh pesto, bruschetta, it’s all good.