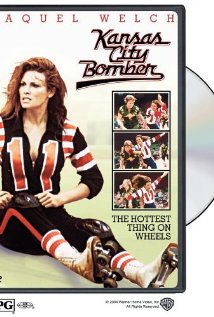

My grandfather used to call my sister Skinny Minnie Miller, because she was skinny, and in praise of his favorite roller derby star.

Roller derby has gone through some sort of nostalgic renaissance of late, or Australia is, as I suspect, stuck in the 1970s, and the wife of one of Amy’s colleagues plays for a touring team out of Brisbane.

Katherine Hobson of NPR reports that Jessica Green, also known as “Thumper Biscuit” for the Emerald City Roller Girls, is also the director of the Biology and the Built Environment Center at the University of Oregon. She and her colleagues just published a study in the journal PeerJ looking at the bacteria that live on the skin of roller derby team members and how they’re swapped around during competition.

According to the official rules of the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association, players are allowed to make contact at the arms, chest, hips and thighs when jockeying for track position.

Researchers swabbed the exposed upper arms of roller derby players on three teams from different cities before and after “bouts” at a tournament in Emerald City’s home base of Eugene, Ore. They found that before a bout, the different teams had distinct populations of skin microbes.

“We could have picked out one player at random, and just by looking at the bacteria on her upper arm, we could have told you what team she played for,” says James Meadow, a postdoctoral researcher at the BioBE Center who led the study.

It’s not entirely clear why the teams had such distinct bacterial communities. It might be because their hometowns of Eugene, San Jose, Calif. and Washington, D.C. have different climates, urban settings and plants and animals, the researchers said. Or the players might have picked them up from some other common environment, like a team van.

But after a bout, the microbes on the players’ arms had more overlap. “We could still tell which team she played for, but with a lot less accuracy,” says Meadow. The results point to person-to-person transmission, though Green says it’s also possible that the bacteria were transmitted by contact with the ground or even through the air. It’s not clear how long the changes seen after a bout would persist, though; that would require looking at players’ skin bacteria over days or weeks.

Noah Fierer, an associate professor at the University of Colorado who studies microbial communities, says the results are in line with other studies showing that bacteria are swapped between people who make other kinds of contact, like shaking hands. (He reviewed the study for PeerJ, a new peer-reviewed, open-access journal at which Green is an academic editor.)

When I think Best Western, I think free wi-fi.

When I think Best Western, I think free wi-fi. of bacteria carried by the Garra rufa, or "doctor fish," an 2.5-cm-long silver carp native to Southeast Asia.

of bacteria carried by the Garra rufa, or "doctor fish," an 2.5-cm-long silver carp native to Southeast Asia. Carrie Zapka from GOJO Industries in Akron Ohio, the lead researcher on the study that also included scientists from BioScience Laboratories in Bozeman, Montana and the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Carrie Zapka from GOJO Industries in Akron Ohio, the lead researcher on the study that also included scientists from BioScience Laboratories in Bozeman, Montana and the University of Arizona, Tucson. an indicator of fecal contamination.

an indicator of fecal contamination..jpg) contamination.

contamination..jpg) Franklin, the BART board president, acknowledged, “People don’t know what’s in there.”

Franklin, the BART board president, acknowledged, “People don’t know what’s in there.” the U.S. wire services. Why the Globe decided to run the story at the end of Dec. 1995 remains a mystery.

the U.S. wire services. Why the Globe decided to run the story at the end of Dec. 1995 remains a mystery.