Coral Beach of The Packer writes that in a cross claim filed June 2 in a Colorado state court, the country’s second largest retailer names Primus and distributor Frontera Produce Ltd. as defendants in the death of a Colorado man who contracted a Listeria monocytogenes infection after eating cantaloupe from the Holly, Colo.

“Primus misrepresented the conditions and practices at Jensen Farms ranchlands and packinghouse by giving it a superior rating and high score despite the existence of conditions and practices that should have caused a failure of the facility,” according to Kroger’s claim.

“Primus misrepresented the conditions and practices at Jensen Farms ranchlands and packinghouse by giving it a superior rating and high score despite the existence of conditions and practices that should have caused a failure of the facility,” according to Kroger’s claim.

Primus has 30 days to respond, but the food safety auditing company has maintained its lack of liability in dozens of cases filed by victims and relatives and in a federal case filed by brothers Eric and Ryan Jensen, owners of the bankrupt cantaloupe operation.

The 2011 listeria monocytogenes outbreak traced to the Jensens’ cantaloupe resulted in 33 deaths and another 147 illnesses across 28 states, according to the Centers for Disease control and Prevention.

Time to change the discussion and the approach to safe food. Time to lose the religion: audits and inspections are never enough.

• Food safety audits and inspections are a key component of the nation’s food safety system and their use will expand in the future, for both domestic and imported foodstuffs, but recent failures can be emotionally, physically and financially devastating to the victims and the businesses involved;

• many outbreaks involve firms that have had their food production systems verified and received acceptable ratings from food safety auditors or government inspectors;

• while inspectors and auditors play an active role in overseeing compliance, the burden for food safety lies primarily with food producers;

• there are lots of limitations with audits and inspections, just like with restaurants inspections, but with an estimated 48 million sick each year in the U.S., the question should be, how best to improve food safety?

• audit reports are only useful if the purchaser or food producer reviews the results, understands the risks addressed by the standards and makes risk-reduction decisions based on the results;

• there appears to be a disconnect between what auditors provide (a snapshot) and what buyers believe they are doing (a full verification or certification of product and process);

• third-party audits are only one performance indicator and need to be supplemented with microbial testing, second-party audits of suppliers and the in-house capacity to meaningfully assess the results of audits and inspections;

• companies who blame the auditor or inspector for outbreaks of foodborne illness should also blame themselves;

• assessing food-handling practices of staff through internal observations, externally-led evaluations, and audit and inspection results can provide indicators of a food safety culture; and,

• the use of audits to help create, improve, and maintain a genuine food safety culture holds the most promise in preventing foodborne illness and safeguarding public health.

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

30.aug.12

Food Control

D.A. Powell, S. Erdozain, C. Dodd, R. Costa, K. Morley, B.J. Chapman

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713512004409?v=s5

Abstract

Internal and external food safety audits are conducted to assess the safety and quality of food including on-farm production, manufacturing practices, sanitation, and hygiene. Some auditors are direct stakeholders that are employed by food establishments to conduct internal audits, while other auditors may represent the interests of a second-party purchaser or a third-party auditing agency. Some buyers conduct their own audits or additional testing, while some buyers trust the results of third-party audits or inspections. Third-party auditors, however, use various food safety audit standards and most do not have a vested interest in the products being sold. Audits are conducted under a proprietary standard, while food safety inspections are generally conducted within a legal framework. There have been many foodborne illness outbreaks linked to food processors that have passed third-party audits and inspections, raising questions about the utility of both. Supporters argue third-party audits are a way to ensure food safety in an era of dwindling economic resources. Critics contend that while external audits and inspections can be a valuable tool to help ensure safe food, such activities represent only a snapshot in time. This paper identifies limitations of food safety inspections and audits and provides recommendations for strengthening the system, based on developing a strong food safety culture, including risk-based verification steps, throughout the food safety system.

.jpg) farm, just a law now on the books that is lagging behind. Until they get their act together, it’s not fair to blame the industry for not getting it together when they themselves cannot.

farm, just a law now on the books that is lagging behind. Until they get their act together, it’s not fair to blame the industry for not getting it together when they themselves cannot..jpg) the problems spread over millions of acres of land and thousands of farming operations. The failures include FDA not being able to enforce rules or educate the industry, and if I sound like I am repeating myself, I am.

the problems spread over millions of acres of land and thousands of farming operations. The failures include FDA not being able to enforce rules or educate the industry, and if I sound like I am repeating myself, I am.(1).jpg) own targeted for the number or frequency of inspections.

own targeted for the number or frequency of inspections.

.jpg) Eldredge, a malpractice and liability specialist who also teaches at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law.

Eldredge, a malpractice and liability specialist who also teaches at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law..jpg) Washington, D.C.-based United Fresh Produce Association. “They are not trusting the third-party audits and they are going out and doing their own inspections as well to verify if the third-party (inspectors) are doing a good job.”

Washington, D.C.-based United Fresh Produce Association. “They are not trusting the third-party audits and they are going out and doing their own inspections as well to verify if the third-party (inspectors) are doing a good job.”.jpg) they naturally cull their flock to get under the wire. But until then, they could be housing more hens to make more profit.

they naturally cull their flock to get under the wire. But until then, they could be housing more hens to make more profit. members cheat on production limits, so why not have some more surprise inspections? The management is obviously aware now of allegations that cracks have made it into the Grade A table market, posing a risk to food safety, so what has it done?

members cheat on production limits, so why not have some more surprise inspections? The management is obviously aware now of allegations that cracks have made it into the Grade A table market, posing a risk to food safety, so what has it done?  want to go back and revisit that, and determine if that’s the best way to go about it. There doesn’t seem to be any sort of plan."

want to go back and revisit that, and determine if that’s the best way to go about it. There doesn’t seem to be any sort of plan.".jpg) because it’s cheaper but because it’s safer.

because it’s cheaper but because it’s safer..jpg) undersecretary of agriculture for food safety at the USDA. "It has a ‘wander around and hope you bump into something’ " approach.

undersecretary of agriculture for food safety at the USDA. "It has a ‘wander around and hope you bump into something’ " approach.

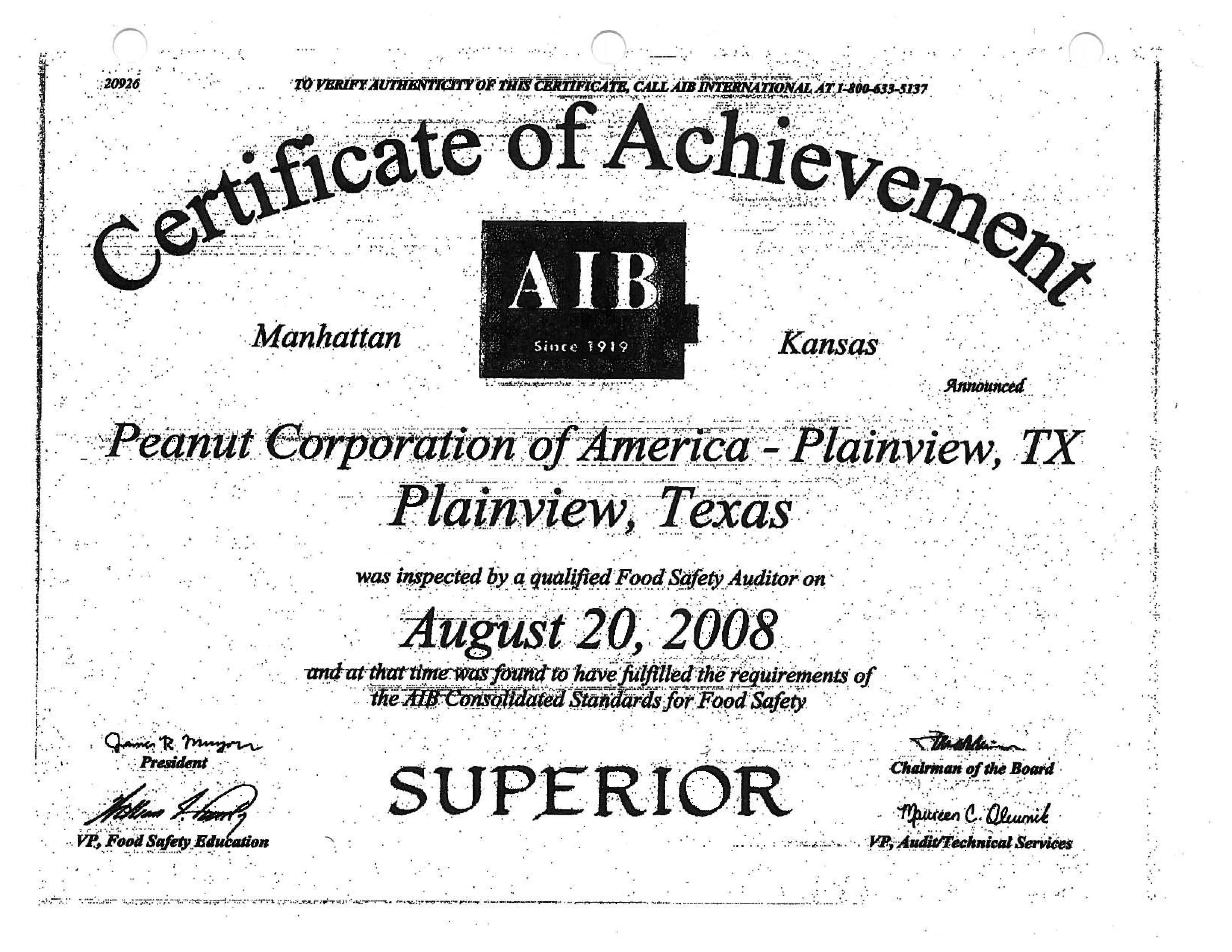

Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below).

Montgomery Burns Awards for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Excellence, courtesy of AIB, the Manhattan, Kansas-based audiots that gave a stellar rating to PCA and Wright Eggs just prior to terrible food safety outbreaks and revelations of awful production conditions (see below)..jpg) The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper.

The vast number of facilities and suppliers means audits are required, but people have been replaced by paper. more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive."

more thorough," said Robert Brackett, former senior vice president of the Grocery Manufacturers Association. "But they’re less likely to be used because they are much more expensive." manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."

manufacturers "guidance and education for improvement."