“The contributions of third-party audits to food safety is the same as the contribution of mail-order diploma mills to education. … I have not seen a single company that has had an outbreak or recall that didn’t have a series of audits with really high scores.”

– Mansour Samadpour, president, IEH Laboratories, Seattle

“No one should rely on third-party audits to insure food safety.”

– Will Daniels, food safety, Earthbound Farm

Billions of meals are served safely each day throughout the world. Much of that food is verified as safe by some form of third-party auditor. Yet when outbreaks of foodborne illness happen, the results can be emotionally, physically and financially devastating. And almost all outbreaks involve firms that have received glowing endorsements from food safety auditors.

Food safety auditors are an integral part of the food safety system, and their use will expand in the future, for both domestic and imported foodstuffs. How then to make third-party audits more .jpg) meaningful, more accurate, and to fully enhance the safety of consumers?

meaningful, more accurate, and to fully enhance the safety of consumers?

There is a long and spectacular history of food safety failures involving third-party audits (and inspections). Many foodborne illness outbreaks have been linked to farms, processors and retailers that went through some form of certification. The U.S. Government Accountability Office noted in a 2008 report that, while inspectors play an active role in overseeing compliance, the burden for food safety lies primarily with food producers.

In late Oct. 1996, an outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 was traced to juice containing unpasteurized apple cider manufactured by Odwalla in the northwest U.S. Sixty-four people were sickened and a 16-month-old died from E. coli O157:H7. During subsequent grand jury testimony, it was revealed that while Odwalla had written contracts with suppliers to only provide apples picked from trees rather than drops – those that had fallen to the ground and would be more likely to be contaminated with feces, in this case deer feces – the company never bothered to verify if suppliers were actually doing what they said they were doing.

Earlier in 1996, Odwalla had sought to supply the U.S. Army with juice. An Aug. 6, 1996 letter from the Army to Odwalla stated, “we determined that your plant sanitation program does not adequately assure product wholesomeness for military consumers. This lack of assurance prevents approval of your establishment as a source of supply for the Armed Forces at this time.”

Five-year-old Mason Jones was one of 157 people – primarily children – who became ill in an outbreak in South Wales caused by E. coli O157:H7 in September 2005. The outbreak was traced to the consumption of cooked meats provided to schools by John Tudor & Son, a catering butcher business. A packaging machine at the business, used for both raw and cooked meats, was identified as the probable source of contamination – where E. coli O157:H7 was most likely transferred from raw meat to cooked meat that was then distributed to four authorities in South Wales for their school meal programs. The 2005 outbreak was the largest caused by E. coli O157:H7 in Wales and the second largest in the United Kingdom to date; ultimately 31 people were admitted to hospital and, tragically, Mason Jones died.

A public inquiry into the outbreak determined that William Tudor, the proprietor of John Tudor & Son, had a significant disregard for food safety and thus for the health of people who consumed meats produced and distributed by his business. The inquiry heard that there had been serious, and repeated, breaches of federal food safety regulations at the catering butcher business. William Tudor had failed to ensure that critical procedures, such as cleaning and the separation of raw and cooked meats, were carried out effectively. He also falsified certain records that were an important part of food safety practice and deceived Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) on issues such as the use of the packaging machine. The business’s Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan was also found to be poorly designed, inaccurate and misleading.

Although foodborne illness may not always be completely preventable, my food safety culture colleague Chris Griffith concluded that the risk of a business causing foodborne illness is, to a large extent, a consequence of its own activities (and its auditors and inspectors).

In Sept. 2006, 199 people were sickened and at least three died from E. coli O157:H7 in bagged spinach produced by Earthbound Farms of California. Samples of river water, wild pig feces, and cattle feces tested positive for the outbreak strain of E. coli O157:H7, and infected feces of nearby grass-fed cattle were found on one of the four fields where the contaminated spinach .jpg) was grown, under organic production standards, in Salinas Valley. There was no verification that farmers and others in the farm-to-fork food safety system were seriously adapting to the messages about risk and the numbers of sick people, and then translating such information into behavioral changes that enhanced front-line food safety practices, especially in production fields rather than just processing facilities.

was grown, under organic production standards, in Salinas Valley. There was no verification that farmers and others in the farm-to-fork food safety system were seriously adapting to the messages about risk and the numbers of sick people, and then translating such information into behavioral changes that enhanced front-line food safety practices, especially in production fields rather than just processing facilities.

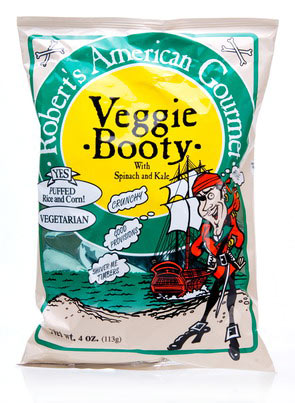

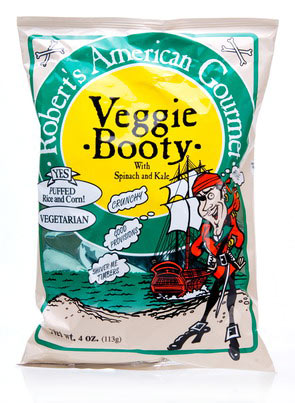

On June 28, 2007 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement warning consumers not to eat Veggie Booty snack food because it had been linked to an outbreak of salmonella.

In July the FDA found Salmonella Wandsworth in the snacks, reconfirming Veggie Booty was the source of the outbreak, after the Minnesota Agricultural Lab had already backed up the epidemiologic evidence with laboratory testing. At the same time, they advised consumers not to eat another product from the same company, Super Veggie Tings Crunchy Corn Sticks, because they might be contaminated as well. Preliminary investigations suggested the seasoning mix might have been the actual source of contamination. The company said the seasoning ingredients came from China, shifting the blame to a country which had failed quality and safety standards for nearly one fifth of their products at the time. A total of 23 states were affected and 69 people became sick.

The plant that made Veggie Booty had received a rating of “excellent” from the American Institute of Baking, raising questions about the efficacy of auditors, which did not extend to ingredient suppliers.

In August 2008, Listeria monocytogenes-contaminated deli meats produced by Maple Leaf Foods, Inc. of Canada caused 57 illnesses and ultimately resulting in 23 deaths. A panel of international food safety experts convened by Maple Leaf Foods, Inc. to investigate the source of the deli meat contamination determined that the most probable contamination source was commercial meat slicers that, despite cleaning according to the manufacturer’s instructions, had meat residue trapped deep inside the slicing mechanisms. The meat residue provided a reservoir and breeding ground for L. monocytogenes. An independent investigative review commissioned by the Canadian federal government provided 57 recommendations to prevent similar outbreaks in the future, reflecting the broad findings of the review: that the focus on food safety was insufficient among senior management at both the company and the various government organizations involved before and during the outbreak; that insufficient planning had been undertaken to be prepared for a potential outbreak; and that those involved lacked a sense of urgency at the outset of the outbreak.

The plant linked to the outbreak received satisfactory marks for complying with federal regulatory requirements. Employees consistently addressed instances of non-compliance when they were identified. The plant’s management maintained all required records, ensured that staff training took place, and ensured the established quality assurance program was followed. At all plants, the company conducted environmental testing that went beyond regulatory requirements. Prior to the outbreak, Maple Leaf Foods, Inc. conducted more than 3,000 environmental tests annually at  the implicated plant and tested products monthly. Although no product tests revealed the presence of Listeria spp., a number of environmental samples detected the bacteria in the months before the public was alerted in August to possible contamination. However, the company failed to recognize and identify the underlying cause of a sporadic yet persistent pattern of environmental test results that were positive for Listeria spp. and was not obliged to report the results.

the implicated plant and tested products monthly. Although no product tests revealed the presence of Listeria spp., a number of environmental samples detected the bacteria in the months before the public was alerted in August to possible contamination. However, the company failed to recognize and identify the underlying cause of a sporadic yet persistent pattern of environmental test results that were positive for Listeria spp. and was not obliged to report the results.

In January 2009, Peanut Corporation of America (PCA) was linked to a growing outbreak across the U.S. caused by Salmonella serotype Typhimurium. On January 9, 2009, the outbreak strain was isolated by the Minnesota Department of Agriculture from an unopened container of King Nut peanut butter – a product manufactured solely by PCA at its facility in Blakely, Georgia. In the ensuing weeks, all peanuts and peanut products processed at Blakely plant since January 1, 2007 were recalled. This included over 3,900 peanut butter and other peanut-containing products from more than 350 companies. PCA supplied peanuts, peanut butter, peanut meal and peanut paste to food processors for use in a wide range of products from cookies, snacks and ice cream to dog treats; to institutions such as hospitals, schools and nursing homes; and directly to consumers through discount retail outlets such as dollar stores. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 691 people were sickened and nine died across 46 U.S. states and in Canada.

Moss and Martin reported in the N.Y. Times that an auditor with the American Institute of baking, based in Manhattan, Kansas, was responsible for evaluating the safety of products produced by PCA. The peanut company knew in advance when the auditors were arriving.

“The overall food safety level of this facility was considered to be: SUPERIOR,” the auditor concluded in his March 27, 2008, report for AIB. A copy of the audit was obtained by The New York Times.

AIB was not alone in missing the trouble at the Peanut Corporation plant in Blakely, Ga. State inspectors also found only minor problems, while a federal team last month uncovered a number of alarming signs, as well as testing records from the company itself that showed salmonella in its products as far back as June 2007.

Nestlé twice inspected PCA plants and chose not to take on PCA as a supplier because it didn’t meet Nestlé’s food-safety standards, according to Nestlé’s audit reports in 2002 and 2006.

“Nestlé audited the Blakely plant in 2002 and rejected it as a supplier. Nestlé’s audit report said the plant needed a "better understanding of the concept of deep cleaning" and failed to adequately separate unroasted raw peanuts from roasted ones. Having them in the same area could allow bacteria on raw nuts to contaminate roasted ones, a risk known as cross-contamination. The plant wasn’t even close to Nestlé’s standards, auditor Richard Hutson said in .jpeg) an interview. Hutson, who now heads quality assurance for several Nestlé divisions, said he shared his concerns with PCA officials at the time, but "they didn’t pursue it" further with Nestlé, he says.”

an interview. Hutson, who now heads quality assurance for several Nestlé divisions, said he shared his concerns with PCA officials at the time, but "they didn’t pursue it" further with Nestlé, he says.”

Kellogg CEO David Mackay testified at a congressional hearing that PCA had been audited by AIB, "the most commonly used auditor in the U.S."

Salmonella in DeCoster eggs in 2010 lead to 2,000 illnesses and the recall of 500 million eggs. They received a superior rating prior to the outbreak from AIB.

That’s a long-winded way of saying, the system of third-party audits can work, but when it fails, it fails spectacularly.

William Neuman of the New York Times reports today the nationwide listeria outbreak that has killed 25 people who ate tainted cantaloupe was probably caused by unsanitary conditions in the packing shed of the Colorado farm where the melons were grown.

Government investigators said that workers had tramped through pools of water where listeria was likely to grow, tracking the deadly bacteria around the shed, which was operated by Jensen Farms, in Granada, Colo. The pathogen was found on a conveyor belt for carrying cantaloupes, a melon drying area and a floor drain, among other places.

This is the part that should give no consumer any confidence:

The farm had passed a food safety audit by an outside contractor just days before the outbreak began. Eric Jensen, a member of the family that runs the farm, said in an e-mail that the auditor had given the packing plant a score of 96 points out of 100.

FDA officials did not criticize the auditor directly. But Michael R. Taylor, deputy commissioner for foods, said the agency intended to establish standards for how auditors should be trained and how audits should be conducted.

The definition of crazy is doing more of the same and expecting a different result: more training will not fix these endemic food safety problems.

Jensen Farms, run by Mr. Jensen and his brother Ryan, had recently acquired a set of used machinery to upgrade the way it washed and dried its cantaloupes. The equipment had been used to clean potatoes and was not intended for use with cantaloupes, officials said. They said the equipment was corroded in places and built in a way that made it difficult to clean and sanitize.

An area used to dry the melons included a cloth cover that could easily have harbored the bacteria, according to a person who discussed the operation with the Jensens.

Officials also said that the cantaloupes had not been adequately cooled before they were placed in refrigerated storage, which could have caused condensation to form on the fruit, creating hospitable conditions for listeria. The bacteria grow well in wet or damp conditions and can also thrive in cold.

Jensen Farms hired an auditor called Primus Labs, based in California, to inspect its facility. Primus gave the job to a subcontractor, Bio Food Safety, which is based in Texas. Jensen and Primus declined to provide a copy of the audit report.

Robert Stovicek, the president of PrimusLabs, said his company had reviewed the audit and found no problems in how it was conducted or in the auditor’s conclusions.

“We thought he did a pretty good job,” Mr. Stovicek said. He said the auditor, James M. DiIorio, has been doing audits for the company since March.

He said that Mr. DiIorio had received two one-week training courses as part of his preparation and had also gone on audits with other auditors.

Asked how Mr. DiIorio could have given high marks to a facility that the F.D.A. described as a breeding ground for listeria, Mr. Stovicek said, “There’s lots of variations as to how people interpret unsanitary conditions.”

Trevor V. Suslow, a professor of food safety at the University of California, Davis, said auditors may give farmers, processors and retailers a false sense of security.

“There needs to be training, certification and auditing of the auditors,” he said.

If third-party auditors and inspectors are part of the food safety solution, then what can be improved? Third-party audits are only one performance indicator but need to be supplemented with microbial testing, second-party audits of suppliers and the in-house capacity to meaningfully assess the results of audits and inspections. Any and all suppliers should be a key focus.

.jpg)

.jpg) minimum credentials, such as the one we found on one company’s website, “high school diploma, or equivalent, plus ten (10) years food processing experience (food plant experience in a responsible food safety position),” then these audits are doomed to be a potentially harmful and indeed can be worthless.

minimum credentials, such as the one we found on one company’s website, “high school diploma, or equivalent, plus ten (10) years food processing experience (food plant experience in a responsible food safety position),” then these audits are doomed to be a potentially harmful and indeed can be worthless. .jpg) improved food safety a great deal. Critics are too ready to dismiss the whole system."

improved food safety a great deal. Critics are too ready to dismiss the whole system.".jpg) changes," Mulhern said in an email. Frontera is looking into whether more steps are needed to validate findings, such as follow-up audits, he said.

changes," Mulhern said in an email. Frontera is looking into whether more steps are needed to validate findings, such as follow-up audits, he said..jpg) of Edinburg, Texas-based Frontera Produce Ltd.

of Edinburg, Texas-based Frontera Produce Ltd. .jpg) "why and how personnel from his company, outside auditors or consultants failed to find these noncompliances," according to a 2007 USDA document.

"why and how personnel from his company, outside auditors or consultants failed to find these noncompliances," according to a 2007 USDA document..jpg) meaningful, more accurate, and to fully enhance the safety of consumers?

meaningful, more accurate, and to fully enhance the safety of consumers?.jpg) was grown, under organic production standards, in Salinas Valley. There was no verification that farmers and others in the farm-to-fork food safety system were seriously adapting to the messages about risk and the numbers of sick people, and then translating such information into behavioral changes that enhanced front-line food safety practices, especially in production fields rather than just processing facilities.

was grown, under organic production standards, in Salinas Valley. There was no verification that farmers and others in the farm-to-fork food safety system were seriously adapting to the messages about risk and the numbers of sick people, and then translating such information into behavioral changes that enhanced front-line food safety practices, especially in production fields rather than just processing facilities. the implicated plant and tested products monthly. Although no product tests revealed the presence of Listeria spp., a number of environmental samples detected the bacteria in the months before the public was alerted in August to possible contamination. However, the company failed to recognize and identify the underlying cause of a sporadic yet persistent pattern of environmental test results that were positive for Listeria spp. and was not obliged to report the results.

the implicated plant and tested products monthly. Although no product tests revealed the presence of Listeria spp., a number of environmental samples detected the bacteria in the months before the public was alerted in August to possible contamination. However, the company failed to recognize and identify the underlying cause of a sporadic yet persistent pattern of environmental test results that were positive for Listeria spp. and was not obliged to report the results..jpeg) an interview. Hutson, who now heads quality assurance for several Nestlé divisions, said he shared his concerns with PCA officials at the time, but "they didn’t pursue it" further with Nestlé, he says.”

an interview. Hutson, who now heads quality assurance for several Nestlé divisions, said he shared his concerns with PCA officials at the time, but "they didn’t pursue it" further with Nestlé, he says.”.jpg) principled auditing firms realize these too simple calculations do not leave them sufficient time to audit as they should. Thus they add additional time resulting in a higher price. In evaluating the differing quotes, plant management all too often choose the least expensive option knowing they will save money. More importantly, they realize the less time the auditor has, the fewer non-conformances they will find. The result: GFSI-light.

principled auditing firms realize these too simple calculations do not leave them sufficient time to audit as they should. Thus they add additional time resulting in a higher price. In evaluating the differing quotes, plant management all too often choose the least expensive option knowing they will save money. More importantly, they realize the less time the auditor has, the fewer non-conformances they will find. The result: GFSI-light..jpg) they naturally cull their flock to get under the wire. But until then, they could be housing more hens to make more profit.

they naturally cull their flock to get under the wire. But until then, they could be housing more hens to make more profit. members cheat on production limits, so why not have some more surprise inspections? The management is obviously aware now of allegations that cracks have made it into the Grade A table market, posing a risk to food safety, so what has it done?

members cheat on production limits, so why not have some more surprise inspections? The management is obviously aware now of allegations that cracks have made it into the Grade A table market, posing a risk to food safety, so what has it done? .jpg) easier-cleaned clover sprouts, effective immediately.

easier-cleaned clover sprouts, effective immediately.