Attorney Bill Marler writes:

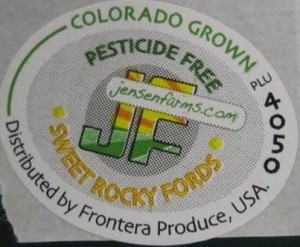

It has been almost three long years since dusty Holly, Colorado, became the epicenter of a Listeria monocytogenes human tragedy. Many are painfully aware that litigation has been ongoing since the fall of 2011. The litigation stems from one of the deadliest foodborne illness outbreaks in United States history. At least 147 people were sickened and more than 33 people died[1]. Since 2011, some of those sickened who survived have died — as have several family members (including spouses) — as they have waited for justice. Several have been left with brain injuries and/or the risk of future complications.

It has been almost three long years since dusty Holly, Colorado, became the epicenter of a Listeria monocytogenes human tragedy. Many are painfully aware that litigation has been ongoing since the fall of 2011. The litigation stems from one of the deadliest foodborne illness outbreaks in United States history. At least 147 people were sickened and more than 33 people died[1]. Since 2011, some of those sickened who survived have died — as have several family members (including spouses) — as they have waited for justice. Several have been left with brain injuries and/or the risk of future complications.

The Outbreak and the Audit

This outbreak began with Primus’ audit on July 25, 2011, at Jensen Farms, continued to stores that enticed customer loyalty (some now refusing to be responsible for what they sold), and ended in hospitals, morgues and rehab centers across much of the western U.S.

After spending the day before production fully started[2] inspecting Jensen Farms, Primus gave Jensen Farms a “96% score” and a “superior rating[3].” Had Jensen Farms failed the audit, the cantaloupes would never have been shipped to consumers across the country. But, Primus sees it differently:

“I understand 96 seems incongruous,” the legal counsel for Primus, attorney Jeffrey Whittington of Kaufman Borgeest & Ryan LLC, has said. “People in the food industry know what that means[4].”

Do we? Others see these audits for what they really have become:

“These so-called food safety audits are not worth anything,” said Dr. Mansour Samadpour, president and CEO of IEH Laboratories, one of the nation’s largest food safety consulting labs for industry. “They are not food safety audits. They have nothing to do with food safety.” Consumers should have no faith in the current system of farm audits because farms pay for their own inspections. “If this industry is sincere and they want to have their products be of any use to anyone, they should be printing their audit reports on toilet paper,” Samadpour said. “People who are commissioning these audits don’t seem to understand that they are … not worth the paper that they’re written on[5].”

The Litigation

There are a total of 66 victim claims in litigation in more than a dozen states. Marler Clark has the honor of directly representing 46 and indirectly several more[6]. Of the 66 claims, 61 of them were valued by the claims administrator in the Jensen Farms bankruptcy, for a total value of $45,595,000. The additional five claims will clearly put a conservative claim value on this litigation of well over $50,000,000.

Primus has expended in excess of $2,500,000 so far on motion practice that will be fully discussed below. Primus’ insurance policy requires it to first consent to any settlement, for which it has shown no interest to date. There is approximately $2,500,000 left on the insurance policy.

Primus has expended in excess of $2,500,000 so far on motion practice that will be fully discussed below. Primus’ insurance policy requires it to first consent to any settlement, for which it has shown no interest to date. There is approximately $2,500,000 left on the insurance policy.

As I have told counsel for Primus, in 20 years of litigating every major foodborne illness outbreak in the U.S., my firm has never sued an auditor. The reasons that we did so in this case are well set out in the FDA report, House subcommittee correspondence and our amended complaints[7]. We certainly knew the legal arguments that we faced. There was a long history insulating auditors/inspectors from liability. I never expected to win all those arguments. However, even winning some has created new law and significant exposure to Primus and the industry despite Primus’ alternative view of the world[8].

Although some retailers — namely Walmart[9] — have resolved claims on behalf of customers, resolution of victims’ claims against Primus is still likely one of the keys to extinguishing this litigation in a manner satisfactory, and fair, to all parties, even Primus. In short, if Primus does not resolve these claims immediately, then it will be bankrupted, whether by jury verdict or its attorneys’ billing, or, more likely, a combination of the two.

Primus’ position, from day one of this litigation, has been to spare no expense in spending down its burning limits policy in total defense of its reputation[10]. To Primus, this case is not about making good business decisions, or about the facts and the law. If it were, then the repeated successes in defeating Primus’ Rule 12(b)(6) motions to dismiss, which are discussed in detail below, would be reason enough to resolve these claims. After all, by the time of trial in any of these cases, Primus is likely to have little left on its $5,000,000 policy, and all it will take is one jury to end Primus forever.

The score on Primus motions to dismiss, as of today’s date, is nine to three[11] — nine courts nationally have agreed that Primus owed duties of reasonable care to consumers and that victims’ complaints sufficiently alleged breach of that duty and causation as well.

The Audit and the Investigation

You may have some sense for Primus’ role in the sequence of events leading to the cantaloupe Listeria monocytogenes outbreak, and I will endeavor to give you the facts as we see them. We have no idea whether the facts as they have developed even matter to Primus, but, ultimately, as the lawyers for people severely injured or killed, they are all that matter to us.

Before getting to that, however, it is worth observing that all victims nationally have been assigned the rights of Jensen Farms against Primus[12]. Clearly, Primus will have significantly more difficulty getting Jensen Farms’ claims for economic injury dismissed because those claims are premised, in part, on the existence of contractual privity between it and Jensen Farms. Thus, Primus’ arguments, addressed below, on the lack of duty owing to consumers of Jensen Farms may ultimately be beside the point. Even if all consumer claims against Primus were dismissed — which will not happen since nine of 12 courts nationally have already ruled in victims’ favor — Primus will still face the certain claims against it by Jensen Farms for breach of contractual and related duties owed during the conduct of the July 25, 2011, audit[13]. Primus will not escape responsibility.

On Sept. 10, 2011, after Jensen Farms cantaloupes had been identified as the source of this outbreak, FDA and Colorado state health officials conducted an inspection at Jensen Farms. They collected multiple samples, both product and environmental, for laboratory testing. Of the 39 environmental swabs collected from within the Jensen Farms packing facility, 13 were confirmed positive for Listeria monocytogenes with PFGE pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from three of the six outbreak strains. Of the 13 positive environmental swabs, 12 were collected at the processing line and one was collected from the packing area. Cantaloupe collected from the firm’s cold storage during the inspection also tested positive for Listeria — in fact, five of the 10 samples collected were positive for Listeria — with PFGE pattern combinations that were indistinguishable from two of the six outbreak strains.

After finding evidence of extensive contamination at Jensen Farms, FDA again, with the assistance of Colorado state officials, conducted an environmental assessment at the facility in an effort to identify the practices and conditions that led to such widespread contamination. The results of the assessment, which occurred on Sept. 22 and 23, 2011, were disclosed in a report dated Oct. 19, 2011. Among other things, the report found faults with Jensen Farms’ facility design, equipment design and post-harvest practices[14].

After conducting this environmental assessment, FDA issued a warning letter to Jensen Farms, indicating, “We may take further action to seize your product(s) and/or enjoin your firm from operating. Additionally, the receipt of this warning letter and any action taken to correct the violations cited in it do not preclude a subsequent criminal prosecution by the United States Department of Justice[15].” The Jensen brothers were later prosecuted and pleaded guilty to manufacturing and shipping adulterated cantaloupe[16].

After conducting this environmental assessment, FDA issued a warning letter to Jensen Farms, indicating, “We may take further action to seize your product(s) and/or enjoin your firm from operating. Additionally, the receipt of this warning letter and any action taken to correct the violations cited in it do not preclude a subsequent criminal prosecution by the United States Department of Justice[15].” The Jensen brothers were later prosecuted and pleaded guilty to manufacturing and shipping adulterated cantaloupe[16].

But the FDA did not close its file on this outbreak after issuing its very clear warning. Officials from the agency also participated in much-publicized briefings with the House Committee on Energy and Commerce in October and December 2011. At those meetings, FDA officials cited multiple failures at Jensen Farms, which, according to the committee report, “reflected a general lack of awareness of food safety principles.” Those failures, several of which draw from the FDA’s Environmental Assessment Report, included:

Condensation from cooling systems draining directly onto the floor;

Poor drainage resulting in water pooling around the food processing equipment;

Inappropriate food processing equipment which was difficult to clean (e.g., Listeria found on the felt roller brushes);

No antimicrobial solution, such as chlorine, in the water used to wash the cantaloupes, and,

No equipment to remove field heat from the cantaloupes before they were placed into cold storage.

In particular, FDA heavily criticized the decision not to chlorinate the water used to wash cantaloupes, despite the fact that the wash was not re-circulated, as well as the use of improper processing equipment in the packinghouse. As is discussed below, both of these factors not only contributed to the cause of the outbreak, but also were the subject of discussion and recommendation by Primus and its agent, Bio Food Safety, during the July 25, 2011, audit at Jensen Farms.

Dr. Trevor Suslow, one of the nation’s top experts on safetly growing and harvesting melons, was shocked to see that on the audit at Jensen Farms:

“Having antimicrobials in any wash water, particular the primary or the very first step, is absolutely essential, and therefore as soon as one hears that that’s not present, that’s an instant red flag,” Suslow said. The removal of an antimicrobial would be cause for an auditor or inspector to shut down an entire operation, he said.

“What I would expect from an auditor,” Suslow said, “is that they would walk into the facility, look at the wash and dry lines, know that they weren’t using an antimicrobial, and just say: ‘The audit’s done. You have to stop your operation. We can’t continue.’”[17]

In short, the general conditions, personnel and facility at Jensen Farms in the summer of 2011 did not just fall well short of good manufacturing practices and industry standards; they also violated FDA guidance on the safe production of cantaloupes. In fact, this is specifically the opinion held by FDA officials who spoke with the committee in October and December: “FDA officials stated that the outbreak could have likely been prevented if Jensen Farms had maintained its facilities in accordance with existing FDA guidance[18].”

The juxtaposition of the condition of Jensen Farms’ facilities at the FDA investigation in September 2011 and the stated condition of Jensen Farms’ facilities and practices (e.g., “96%/Superior” rating) during the July 25, 2011, audit is central to this case.

Perhaps members of the House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce have the audit problem correct:

There are inherent conflict of interest concerns with the third party auditor relationship. Although large purchasers must approve auditors (and in the case of Jensen Farms (sic, Frontera), provided a list of pre-approved auditors that were to be used), Jensen Farms made the final decisions about which of these specific auditors to hire. This creates a conflict for the auditor: a failing audit has significant economic implications for the producer, to the extent an auditor applies more demanding food safety standards, and it may be less likely to be hired by a given producer. This inherent conflict may account for the extraordinarily high pass rates — above 97% — for Primus Labs audits[19].

In the wake of this monumental outbreak, the prevailing system for third-party audits has come under intense scrutiny. Time and again, this firm has represented injured people, or the families of those who have died, in outbreaks where a negligent processor was given glowing reviews only for investigating agencies later to find during unbiased, competent investigations done without the veneer of conflicting interests that the facility in which the food was produced was not suitable for the production of CAFO[20]-destined animal feed, much less food for human consumption. And, clearly, Jensen Farms’ packing facility was no exception.

Will Steele (president of Frontera):

“In the wake of this experience, we are examining, among other things, the role of audits. Third-party audits are an important and useful tool, but they are obviously not fail-safe. Audits provide baseline information on conditions at the time they are conducted. So we are looking at possible changes that might further enhance food safety. One area of focus is whether additional steps are needed to validate the audit findings regarding food safety protocols that are in place. Validation could be in the form of a follow-up audit, or perhaps other measures that will help provide additional assurance of food safety compliance.”

As has been widely reported, Jensen Farms’ facility was audited by Primus[21] agent Bio Food Safety on July 25, 2011, mere days before the first illness was reported. Auditor James DiIorio gave the facility a “superior” rating and a score of 96 percent, noting that many of the pieces of equipment, and many of the packing procedures in place that FDA found so problematic, were in “total compliance.” Undoubtedly auditing companies will respond and have, in fact, done so, that they only conduct the type of audit they are asked to do, but this argument goes only so far when juxtaposed against the egregious safety, processing and equipment failures that led to this outbreak.

Mr. DiIorio did identify several deficiencies in his facility audit, which lasted just over four hours, including three “major deficiencies”: (1) wood, which is a material universally known for its propensity to act as a reservoir for contamination, was used in the construction of the unloading and packing tables; (2) lack of hot water at hand-washing stations, and (3) doors left open during operating hours, potentially allowing pests to enter the facility. Mr. DiIorio also identified multiple “minor deficiencies” and non-compliances, including: (1) the storage area was left open during operating hours; (2) there were no records of corrective actions taken based on previous audits, and (3) stickers on pest control devices were in the wrong location.

These violations certainly were properly noted, regardless of the type and style of audit that Frontera required.[22] But the truth, however, is that Mr. DiIorio failed to deduct points for several other non-compliances that should have caused Jensen Farms to automatically fail. All of the following must be considered alongside what is not only the obvious, but also the stated, primary concern for Primus audits: “Auditors should interpret the questions and conformance criteria in different situations, with food safety and risk minimization being the key concerns.”[23]

Again, the condition of Jensen Farms’ facility on review by FDA and Colorado state officials simply cannot be reconciled with the glowing review that Mr. DiIorio gave the facility and farms on July 25, 2011.[24] Auditors cannot be as hamstrung as public comments since publication of Mr. DiIorio’s audits have suggested; otherwise, the entire system is a farce, which may well be the point after all.

Of course, this is clearly not Primus’ view, at least not according to public comments since the date that Mr. DiIorio’s audit was first exposed. Robert Stovicek, president of Primus, has repeatedly defended the audit. “Even though it looks as horrendous as it does,” he stated in an interview with the Denver Post,[25] Stovicek indicated that he would continue using Bio Food Safety as its auditing agent, that he had full confidence in Mr. DiIorio,[26] and even that Mr. DiIorio did a “good job,”[27] despite not knowing whether Mr. DiIorio had ever even audited a cantaloupe operation before.[28]

One issue not noted in the foregoing list, instead being reserved for discussion here, is Jensen Farms’ failure to use an antimicrobial in the wash system. Mr. DiIorio prominently noted on the front page of his facility audit report that this is “a packing facility for cantaloupes which are washed by a spray bar roller system, graded, sorted by size, packed into cartons and stored in dry coolers. No anti-microbial solution is injected into the water of the wash station.”[29]

This was not just a simple violation, or something that Mr. DiIorio should have down-scored Jensen Farms’ facility for in some fashion. It was a clear and present threat to human health, and, if third-party audits, regardless of their type, are good for anything other than to rubber-stamp the requirements of major retailers, it must be to identify exactly this type of hazard and act in some fashion — e.g., fail the auditee — to ensure that the risk presented is not merely passed along to consumers.

The lack of an antimicrobial solution has been widely criticized by many experts, from FDA, academia and industry, as violating good agricultural and manufacturing practices, as well as baseline industry standards for the production of cantaloupes. Further, the lack of an antimicrobial must be viewed alongside Mr. DiIorio’s observation at section 1.4.8 that no antimicrobial was being used during cleaning of Jensen Farms’ equipment either. Any auditor, just like any food processor, must, in part, assume contamination of product so that he or she can objectively and effectively assess the facility’s ability to remove or eliminate the contamination. Assuming contamination of Jensen Farms’ cantaloupes, what could Mr. DiIorio possibly have thought would be the barrier to contamination of finished product? No antimicrobial in the wash system, and none used during cleaning of the equipment, is a recipe for exactly the kind of disaster that unfolded — a risk that was only heightened by the inadequacy of Jensen Farms’ operations generally.

We would, of course, be remiss to fail to point out that, in this case, Mr. DiIorio was more than just an auditor. Public statements made since the circumstances underlying this outbreak came to light have suggested that an auditor’s role, under the prevailing system, is quite limited. Whether true or not, Mr. DiIorio’s role was more than that, causing him, the company that he worked for, and Primus, for whom he was also acting as agent, to undertake a further duty to those in the foreseeable zone of risk created by their actions or inactions[30]. More specifically, in interviews with the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Eric and Ryan Jensen stated that Mr. DiIorio actually recommended the faulty production equipment, including the potato washer sold to it by Pepper Equipment, and other practices that Jensen Farms had put in place for the 2011 cantaloupe season. “According to FDA officials, there were ‘serious design flaws’ with the equipment that the auditor recommended, and it did not meet basic standards spelled out in FDA guidance[31].”

Does an Auditor have a Duty to Consumers?

In short, the directive from Primus to its lawyers has been to conduct this litigation in a scorched-earth fashion, leaving no argument unmade, even frivolous ones[32]. In keeping with this, Primus has filed a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss in every case except those filed in Texas. In each motion, Primus has challenged every element of the case against it, from duty to breach to causation to damages. As set forth previously, 12 courts have ruled on the motions, with nine rulings favorable to victims and three to Primus.

There are 26 cases venued in Colorado. One Colorado trial court has already ruled on Primus’ motion to dismiss before the cases were recently consolidated. That ruling occurred in the Hauser matter, where the trial judge at first granted Primus’ motion based on Colorado’s observance of the misfeasance/nonfeasance distinction, but reconsidered his ruling on the motion for reconsideration. Ultimately, the court in the Hauser matter reinstated the case against Primus based on the theory of liability arising from Restatement 2d of Torts § 324A.[33]

An understanding of the § 324A claim is essential to any review of victims’ claims nationally against Primus. To date, the courts in Colorado (e.g., the Hauser court), Louisiana, Nebraska, Oklahoma and others have relied heavily on § 324A in denying Primus’ motions to dismiss. The theory is simple and straightforward, and, as the language of § 324A below would suggest, its application to the facts of this case is clear:

One who undertakes, gratuitously or for consideration, to render services to another which he should recognize as necessary for the protection of a third person or his things, is subject to liability to the third person for physical harm resulting from his failure to exercise reasonable care to protect [perform] his undertaking, if:

(a) His failure to exercise reasonable care increases the risk of harm, or

(b) He has undertaken to perform a duty owed by the other to the third person, or

(c) The harm is suffered because of reliance of the other or the third person upon the undertaking.

Applied against Primus, the sequential evidentiary analysis is as follows: (1) Primus undertook to render services for Jensen Farms by conducting the July 25, 2011, audit; (2) the purpose of Primus’ audit was to ensure that the Jensen Farms facility and practices were in keeping with Good Agricultural Practices and industry standards (the relevant standards of care); (3) the reason for the audit was, ultimately, to ensure that Jensen Farms’ one commodity was safe for consumption by human beings; therefore, Primus should have recognized that the audit was necessary for the protection of a certain group of “third person[s]”; (4) Primus failed to conduct the audit using reasonable care, and (5) consumers of Jensen Farms cantaloupes were injured because Jensen Farms relied on Primus’ audit.

Primus’ arguments on breach, causation, and damages are fact-intensive and are therefore really only relevant in assessing what a jury will ultimately say. With respect to breach, we do not believe that many juries will be able to reconcile the glowing review issued to Jensen Farms by Primus (e.g., “96%/Superior” rating) with the condition of the facility on a more objective assessment by FDA and Colorado state health officials approximately one-and-a-half months later.

Further, with respect to breach, it is important to note that Primus failed to follow its own guidelines in the conduct of the July 25, 2011, audit. Primus has long contended that the parameters for its audit of Jensen Farms were very narrow and did not require any assessment or action beyond the questions/issues identified in its audit report. However, our investigation has revealed internal audit guidelines that Primus is required to follow during an audit but did not.

Primus’ arguments on causation and damages are even less compelling. We recognize that the primary argument against victims’ claims concerns Primus’ duties to consumers of Jensen Farms cantaloupes.

Condensed as far as reasonably possible, Primus has consistently made two arguments as to why it owed no duty of care to consumers of Jensen Farms cantaloupes. First, consumers were not foreseeably affected by its negligence, and second, consumers were not in privity of contract with Primus.

With respect to foreseeability, most courts that have ruled on Primus’ motions have not struggled with this issue. The victims’ case, very simply, is that they were the known and intended users of the single commodity produced by the entity that Primus audited, and the utility of a “food safety audit” by a “food safety auditor” such as Primus is nonexistent if it is not to make products safe (e.g., not contaminated by harmful pathogens) for human consumption. Victims, as consumers of Jensen Farms cantaloupes, were eminently foreseeable to Primus.

Primus itself has made party admissions establishing that consumers were foreseeable. On Oct. 21, 2011, as the full scope of the cantaloupe outbreak was becoming apparent, Primus stated as follows in a press release entitled, “At least 25 People have died and 123 sickened by the Cantaloupe Crisis—How PrimusLabs Works to Minimize These Disasters:”

PrimusLabs cannot count the lives saved through the decades of servicing the fresh produce industry. Unfortunately, we can only pray and mourn for the lives that have been lost due to the unfortunate circumstances that were beyond our control. Every Life is precious. For over 20 years our passionate commitment at PrimusLabs is food safety and minimizing illness and death from fresh produce.

To succeed on its claim that consumers were not foreseeable, whether at trial or on a motion, Primus will have to establish that it could not reasonably have expected consumers of Jensen Farms cantaloupes to be imperiled by a negligently done food safety audit. To make that claim in the face of both common sense and the Oct. 21, 2011, press release will only make juries mad. Primus knows that it is a food safety audit, it knows that it audits companies that produce food for human consumption, and it knows that the primary risk associated with not doing its job properly is people getting sick.

For its privity argument, Primus has inappropriately tried to bootstrap in a privity requirement that arose in a line of cases dealing with negligently done accounting audits.

The Restatement section that Primus bases its privity argument on is Restatement 2d of Torts § 552. The several states have all either adopted § 552, or created rules requiring some level of privity in relevant factual scenarios. By its own terms, however, § 552 is confined to business transaction resulting in “pecuniary loss” and has been applied exclusively in cases dealing with negligently done accounting audits where the injury was only pecuniary in nature. § 552 simply does not apply in situations involving negligent misrepresentations (e.g., audit reports) causing physical injury. If the words of § 552 leave any room for doubt, Comment (a) to § 552 does not:

Although liability under the rule stated in this Section is based upon negligence of the actor in failing to exercise reasonable care or competence in supplying correct information, the scope of his liability is not determined by the rules that govern liability for the negligent supplying of chattels that imperil the security of the person, land or chattels of those to whom they are supplied (see §§ 388-402), or other negligent misrepresentation that results in physical harm. (See § 311). When the harm that is caused is only pecuniary loss, the courts have found it necessary to adopt a more restricted rule of liability, because of the extent to which misinformation may be, and may be expected to be, circulated, and the magnitude of the losses which may follow from reliance upon it.

There is simply no requirement in the law of any relevant state that a victim in a personal injury case asserting claims of negligent misrepresentation must have specifically relied on the misrepresentations for the misrepresentations to be actionable.

Perhaps some of the “new law” that Primus has helped create in the Beach case, both by its bad audit and litigation approach, serves as a proper conclusion:

While the degree of certainty of harm to Mr. Beach is not decisively in favor of imposing a duty in this instance, there is certainly moral blame that can be attached to Primus Group’s conduct due to the alleged large oversights committed during the July 25, 2011 audit. Additionally, there is clearly a need to prevent future harm in situations like this, where innocent consumers eat what they think to be healthy food, which turns out to be contaminated with a potentially lethal pathogen. Further, imposing such a duty neither places an inordinately heavy burden on food safety auditors, nor causes great consequences to the community. In fact, the burden placed on food safety auditors remains unchanged — had the audit not reflected that the packing facility was in total compliance with food safety standards when it allegedly was not, Primus Group presumably would not have been named as a party in this case, if this case had filed. Finally, although not briefed on the issue, it certainly stands to reason that there is insurance available for food safety auditors in conducting food safety audits, just as there is malpractice insurance for doctors or lawyers.

Whether victims succeed in the injury lawsuits against Primus verges on irrelevance at this point. Primus will cease to exist by its own attorneys’ billings or by jury verdicts against it. Most likely, it will be a combination of the two.

One thing has become increasingly clear over the past three years — this litigation[34] will force the third-party audit industry to change, and perhaps my clients will find some small solace in that. Yes, the audit industry and their masters at major retailers should have changed this farce long ago, and, yes, our government should have enacted legislation to more adequately assure the public that someone you love is not killed by a cantaloupe. However, this is why the civil justice system exists — there are times when consumers must take responsibility when those who should have did not, and that is exactly what we are doing.

Thanks to Drew Falkenstein, Andy Weisbecker and Debbie Carr.

[1] Website: http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/cantaloupes-jensen-farms/index.html

[2] “Pursuant to (Primus’) own guidelines, the audit was to be immediately terminated” if the packinghouse was not operating in a normal fashion. See Jensen Farms v. Primus Complaint, Attachment No. 1.

[3] See Jensen Farms Audit, Attachment No. 2. Frontera has not disputed Plaintiffs’ allegation that it would not have marketed the cantaloupe if the Primus audit had failed the JFP (See, Frontera’s Answer and Cross Claims, ¶¶ 15, 17). Moreover, this undisputed fact must be taken as true for purposes of Primus’ Motion to Dismiss.

[4] Website: http://www.thepacker.com/fruit-vegetable-news/Jensens-seek-probation-as-PrimusLabs-denies-liability-240645421.html?view=all

[5] Website: http://www.cnn.com/2012/05/03/health/listeria-outbreak-investigation/

[6] Website: http://www.marlerclark.com/case_news/view/jensen-farms-rocky-ford-cantaloupe-listeria-outbreak-colorado-new-mexico

[7] See Amended Complaint, Attachment No. 3.

[8] See Primus’, The Outbreak: The Untold Story of Listeria Monocytogenes At Jensen Farms, Attachment No. 4.

[9] To date Kroger, like Primus, has taken the position that it has no responsibility for the product/services that it sells to consumers. Kroger, like many large retailers today, takes the position that it contracts away its liability to consumers to broker/shipper/manufacturers like Frontera that supplied it the Jensen Farms’ cantaloupe. Despite requiring inadequate insurance, and having little concern with the supplying company’s assets, Kroger essentially claims it is the victim. The problem for real victims is that Frontera, like Jensen Farms, is woefully underinsured and will be unable to compensate the sick, or the families of the dead, for their legitimate injuries caused by purchasing a cantaloupe from their local Kroger. Kroger’s position will likely push Frontera into bankruptcy. See Attachment 5. See also, “Why Food Retailers Really Don’t Care” – http://www.marlerblog.com/lawyer-oped/why-food-retailers-really-dont-care/#.U8wI91a4lSU. Think about this the next time you walk into a grocery store.

[10] Primus’ litigation strategy has done nothing to remedy its reputation, and, in fact, has created a road map for future litigation against all auditors, not just Primus.

[11] The nine wins are in: Rutherford, Beach, Hauser, Onsager, Pumphrey, Underwood, Gilbert, Drinkwalter and Braddock. The three losses are in: Corsi, Babcock and Lopez Order.

[12] Website: http://producenews.com/news-dep-menu/test-featured/11791-marler-jensen-case-sending-shockwaves-through-the-produce-industry

[13] See Jensen Farms v. Primus Complaint, Attachment No. 1.

[14] See FDA Environmental Assessment Report, Attachment No. 6.

[15] See FDA Warning Letter to Jensen Farms, Attachment No. 7.

[16] See Jensen Plea Agreement, Attachment No. 8.

[17] Website: http://www.cnn.com/2012/05/03/health/listeria-outbreak-investigation/

[18] See Energy and Commerce Committee Report, Attachment No. 9.

[19] See Committee on Energy and Commerce January 10, 2012 Letter to FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, Attachment No. 10.

[20] “CAFO” stands for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation.

[21] Primus is one of the nation’s largest third-party food safety auditors. Primus conducts approximately 15,000 audits per year, primarily involving fresh produce facilities, for more than 3,000 clients worldwide. A typical facility is audited once per year, and a Primus audit results in a pass/fail determination, a score from 0-100 percent, and a report that lists any violations. Passing scores can differ greatly: a company can pass with comment, pass without comment, or pass with either major or minor compliance issues. A company fails if it has one “egregious” non-compliance, or if it scores less than 80 percent overall. According to Primus, the vast majority of the thousands of audits it conducts each year receive grades: 98.7 percent in 2010, 97.5 percent in 2009, and 98.1 percent in 2008.

[22] In fact, the “type and style” of the Jensen Farms audit required by Frontera Produce, no doubt at the insistence of major retailers like Walmart, was a checklist-style audit to ensure compliance with industry standards for the safe production of cantaloupes.

[23] This quotation is from Primus audits manual, revised in November 2011, after it was sued in the Wilcox matter. The manual goes on to state, “[w]here laws, commodity specific guidelines and/or best practice recommendations exist and are derived from a reputable source these practices and parameters should be followed if they present a higher level of conformance than those included in the audit scheme system.”

[24] Unlike the audits performed before the Salmonella outbreaks involving the Peanut Corporation of America and Wright County Egg, the Jensen Farms audit was performed during the outbreak.

[25] Website: http://www.denverpost.com/search/ci_19159245.

[26] Website: http://www.denverpost.com/search/ci_19159245.

[27] Website: http://www.thepacker.com/fruit-vegetable-news/jensen-farms-earned-hight-third-party-audit-marks-132272688.

[28] Website: http://www.denverpost.com/search/ci_19159245.

[29] The July 2011 audit, however, did not mark the beginning of the relationship between Jensen Farms and Primus/Bio Food Safety. On Aug. 5, 2010, Jerry Walzel, the president of Bio Food Safety, audited the Jensen Farms packing facility and gave it a score of 95 percent grade — another “superior” rating — despite also finding several major and minor deficiencies. One precaution that Jensen Farms took in 2010, which it dropped in 2011, was to use an antimicrobial solution, such as chlorine, in the cantaloupe wash water. The front page of the August 2010 audit stated, “[t]his facility packs fresh cantaloupes from their own fields into cartons. The melons are washed and then run through a hydrocooler, which has chlorine, added to the water. Once the product is dried and packed into cartons it is placed into coolers.” After the August 2010 audit was completed, one of the Jensen brothers informed Mr. Walzel that they were interested in improving their processes. According to Jensen Farms, in response to this inquiry, Mr. Walzel indicated that they should consider new equipment to replace the hydrocooler the farm used to process cantaloupe. Mr. Walzel stated that the hydrocooler, with its recirculating water, was a potential food safety “hotspot” and advised them to consider alternate equipment. Based on his comments and input from a local equipment broker, Jensen Farms purchased and retrofitted equipment previously used to process potatoes. The Jensen brothers stated that they changed from the hydrocooler to the new food processing equipment in an attempt to strengthen their food safety efforts. When questioned by the committee about his recommendations to Jensen Farms following the 2010 audit, Mr. Walzel indicated that he could not remember whether he had made these recommendations.

[30] See The Primus Audit Failures and Victims’ Allegations, Attachment No. 11.

[31] See Committee on Energy and Commerce January 10, 2012 Letter to FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, Attachment No. 10.

[32] “Because Primus Group’s arguments concerning its common law duty can be boiled down to a mischaracterization of what is required of the pleadings at this stage, the Court will not reconsider its prior finding concerning Primus Group’s common law duty. Moreover, in arguing that Plaintiffs neither alleged any of Mr. Dilorio’s findings after he conducted the audit, nor alleged any action taken by Jensen Farms based upon Mr. Dilorio’s findings, Primus Group is mistaken. Primus Group’s arguments concerning § 324A(c) suffer from similar inadequacies. Finally, in an attempt that can be described as frivolous at best, Primus Group argues that Plaintiffs’ Complaint failed to establish a duty under Oklahoma’s third-party beneficiary theory due to a lack of supporting evidence.” See Beach Order.

[33] Primus attempted to take an interlocutory appeal of this ruling to the Colorado Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals rejected the effort and declined to consider the appeal. What weight or effect the Hauser Court’s ruling will have on the Colorado Courts ultimate ruling on Primus’ motion to dismiss is not known, but plaintiffs nonetheless believe that application of 324A to plaintiffs’ claims in Colorado is clear.

[34] Website: “Civil litigation is a really blunt instrument for social change,” he said. “There are other ways to deal with things that are appropriate, but sometimes it’s a last resort.” http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2012/06/food-safety-attorney-bill-marler-delivers-food-bank-safety-keynote/#.U8wxDVa4lSU

This week’s Guardian investigation prompted emergency reviews by three of the UK’s leading supermarkets, and the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, intervened on Thursday to demand that the FSA investigate more thoroughly, just hours after the agency had said it was content that correct procedures had been followed.

This week’s Guardian investigation prompted emergency reviews by three of the UK’s leading supermarkets, and the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, intervened on Thursday to demand that the FSA investigate more thoroughly, just hours after the agency had said it was content that correct procedures had been followed.