The dean of Canadian food and farm reporting, Jim Romahn, has written a powerful piece about the continuing failures in Canadian meat inspection – failures that had to be pointed out by Americans.

More than a year after 21 people died after eating Maple Leaf Foods Inc. products contaminated with Listeria monocytoges, the Canadian Food  Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified.

Inspection Agency was failing to enforce its own standards and there was sloppy follow-up when hazardous conditions were identified.

Those worrisome facts are contained in a report prepared by two U.S. inspectors who visited in the fall of 2009 to check Canada’s compliance with its own standards. They visited headquarters in Ottawa, 23 meat-processing plants and two labs.

They found that the Canadian Food Inspection Agency generally has good manuals and intentions, but falls short at the plant level, including failures to identify lax sanitation and to enforce its standards.

Thirty years ago, when Canadian reporters began to obtain U.S. inspection reports on our packing plants, all of the deficiencies identified applied to specific problems and individual plants. This audit has identified similar deficiencies at the plant level, but far more serious, it found deficiencies in the overall system.

Had the U.S. inspectors not checked it’s likely that the deficiencies would have persisted, putting Canadian consumers at risk and the meat industry under threat of losing export markets.

The report also indicates some of the systemic deficiencies were identified during previous annual audits, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency promised to fix them, but they persisted. This is after the Maple Leaf crisis and frequent promises by Agriculture Minister Gerry Ritz and Prime Minister Stephen Harper that corrective action would be taken as swiftly as possible.

They have never talked about the U.S. audit reports that highlighted things that needed attention.

During the inspections of 23 plants – Canadian officials went along with the two U.S. officials – they identified problems so serious that three plants were banned from marketing their products in the U.S. and three more were issued warnings that they would be banned if they failed to immediately correct deficiencies.

Four of these six plants were processing ready-to-eat meat products, meaning they would go directly to consumers without any further steps to eliminate hazardous bacteria.

They also found by checking records that some of the plants were running overtime hours without any government inspectors checking conditions.

At another plant, they said the documents that indicated compliance “did not consistently reflect the conditions encountered at the time of the  audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”

audit.” Later in the report, they write “the actual conditions of the establishment visits were often not entirely consistent with the corresponding documentation.”

Supervisors are supposed to periodically check the performance of front-line government inspectors, but the auditors found “system weaknesses . . . in the manner in which supervisory reviews were conducted.”

They also said there was “an inconsistent identification of potential non-compliances or potential inadequate performance by the inspection personnel.

“The deficiency concerning the lack of supervisory documentation is a repeat finding from the 2008 audit,” this report says.

The two U.S. auditors say the Canadian Food Inspection Agency needs to improve its communications its employee training and awareness and its feedback systems.

They found inspectors were failing to do their duties, as outlined in agency manuals, because they noticed:

– “Lack/loss of consistent identification of contaminated product and product-contact surfaces and other insanitary (sic) conditions.

– “Inconsistent verification of adequate corrective actions . . . with regards to repetitive non-compliances.

– “Inconsistent and loss of documentation of non-compliances in a manner that reflects actual establishment conditions, and

– “Lack/loss of increased inspection activities when non-compliance is observed . . .”

They add that “many of these findings are closely related to those identified during the previous audit.”

They also “identified system weaknesses regarding implementation and verification of HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points) systems within the CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency).”

More specifically, they identified “inaccurate analyzing of hazards” for HACCP protocols, “Inadequate implementation of basic elements of the HACCP plan, including monitoring and ongoing verification procedures” and “inappropriate verification of corrective actions taken in response to deviations from the critical limit (for harmful bacteria)”

In addition, they identified lapses in recording instances of non-compliance, such as failures to enter problems in the record book, failures to identify the level of bacterial contamination ad failure to record  the “actual times when the entries were made.” They also noted that border inspectors conducting spot checks of Canadian hamburger heading to customers in the U.S. found “several occurrences of zero-tolerance failures in addition to two positive results for E. coli O157:H7.”

the “actual times when the entries were made.” They also noted that border inspectors conducting spot checks of Canadian hamburger heading to customers in the U.S. found “several occurrences of zero-tolerance failures in addition to two positive results for E. coli O157:H7.”

Between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31, the U.S. border inspectors turned back 61 million pounds of Canadian meat, calling for repeat inspection by Canadians, and rejected 7,277 pounds that “involved food-safety concerns.” Labeling could be the problem with some of the shipments that were sent back.

In response to this audit, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency said it would increase inspections at 126 of the 190 plants certified to export to the U.S. There is no mention of what will happen at plants selling only to Canadians.

They say “supervisors are now required to accompany inspectors on a quarterly basis. . .”

“The sanitation task was re-structured to focus more on a global assessment of plant sanitation including more emphasis on Ready-to-Eat areas and equipment.”

The CFIA is also stepping up its training programs, its identification of critical control points for its HACCP protocols, its “Listeria related inspection tasks associated with operational/pre-operational sanitation, ventilation (e.g. condensation), building construction and maintenance of equipment.”

The CFIA also says “an electronic application is being developed to allow inspection staff access to historical data at the field level which will provide for more timely compliance decisions.”

When he was asked about the audit, Agriculture Minister Ritz said he has committed an additional $75 million to meat inspection since that audit was completed.

The results of the 2010 audit are not yet available from U.S. officials.

facilities in North America.

facilities in North America..jpg) picture of the conditions at some of Canada’s meat and poultry plants where sanitation problems persisted.

picture of the conditions at some of Canada’s meat and poultry plants where sanitation problems persisted. put on for the auditor for those two or three days. With the pressure of an audit, it is too easy for plant staff and management to forget that the goal of food safety programs is simply not the short-term one of passing the audit, but the ultimately more important one of producing safe food for the consumer. Easily said, but the reality of day-to-day operations in a food plant can make the result very different from the principle. For one thing, an audit must get past the enthusiastic descriptions of a few people and assess the food safety attitude, or culture, of the entire group. Any blame there might be for the thoroughness (or lack thereof) of audits obviously does not rest entirely with auditors, but must also be shouldered by Plant Managers and QA Managers who may feel it necessary to create these “shows” for the auditors without realising how putting on a “show” sends the plant the message that food safety is just a game. Perhaps that is why we see so little progress in reducing recalls and protecting the consumer.

put on for the auditor for those two or three days. With the pressure of an audit, it is too easy for plant staff and management to forget that the goal of food safety programs is simply not the short-term one of passing the audit, but the ultimately more important one of producing safe food for the consumer. Easily said, but the reality of day-to-day operations in a food plant can make the result very different from the principle. For one thing, an audit must get past the enthusiastic descriptions of a few people and assess the food safety attitude, or culture, of the entire group. Any blame there might be for the thoroughness (or lack thereof) of audits obviously does not rest entirely with auditors, but must also be shouldered by Plant Managers and QA Managers who may feel it necessary to create these “shows” for the auditors without realising how putting on a “show” sends the plant the message that food safety is just a game. Perhaps that is why we see so little progress in reducing recalls and protecting the consumer. volumes of paperwork and perhaps even return visits to resolve Major non-conformances. As a result, an auditor may choose to downgrade Major non-conformances Minor, and Minors to Observations.

volumes of paperwork and perhaps even return visits to resolve Major non-conformances. As a result, an auditor may choose to downgrade Major non-conformances Minor, and Minors to Observations. .jpg) safety messages with consumers and other humans was a global phenomenon.

safety messages with consumers and other humans was a global phenomenon..jpg) directly to consumers rather than the local/natural/organic hucksterism is a way to further reinforce the food safety culture.

directly to consumers rather than the local/natural/organic hucksterism is a way to further reinforce the food safety culture. 2010, just as thousands of Americans began barfing from salmonella in DeCoster eggs.

2010, just as thousands of Americans began barfing from salmonella in DeCoster eggs. peanut products shipped from that plant and another PCA plant in 2007 and 2008 sickened as many as 600 people and may have contributed to nine deaths.

peanut products shipped from that plant and another PCA plant in 2007 and 2008 sickened as many as 600 people and may have contributed to nine deaths.

.jpg) recalled, including over 3,900 peanut butter and other peanut-containing products from more than 350 companies. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 691 people were sickened and nine died across 46 U.S. states and in Canada from the outbreak.

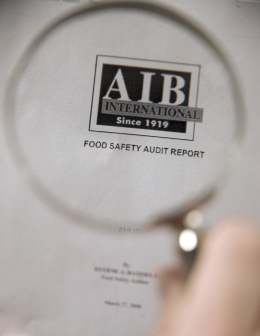

recalled, including over 3,900 peanut butter and other peanut-containing products from more than 350 companies. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 691 people were sickened and nine died across 46 U.S. states and in Canada from the outbreak.(1).jpg) bays and the air conditioning intakes in the roof that provided pests with open access to the plant. Despite these deficiencies, PCA maintained the highest possible rating from auditing firm AIB International.

bays and the air conditioning intakes in the roof that provided pests with open access to the plant. Despite these deficiencies, PCA maintained the highest possible rating from auditing firm AIB International..jpg) with food safety. The Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association explains excetpts below from a submission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on ways to improve preventative controls for produce safety (thanks to

with food safety. The Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association explains excetpts below from a submission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on ways to improve preventative controls for produce safety (thanks to  The Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association supports a common foundation with the updating of the 1998 FDA guidance. We feel any federal food safety program, guidance and/or oversight should consist of science based regulations. This is one area that will require substantial time and resources as the research is simply not available. One example is water quality. In the absence of definitive microbial standards for irrigation water, the authors of the California Leafy Greens Market Agreement Best Practices Document have chosen to use the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recreational water standards. Scientific research is needed to show if these standards are appropriate for irrigation water. …

The Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association supports a common foundation with the updating of the 1998 FDA guidance. We feel any federal food safety program, guidance and/or oversight should consist of science based regulations. This is one area that will require substantial time and resources as the research is simply not available. One example is water quality. In the absence of definitive microbial standards for irrigation water, the authors of the California Leafy Greens Market Agreement Best Practices Document have chosen to use the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s recreational water standards. Scientific research is needed to show if these standards are appropriate for irrigation water. … has an important role in food safety, but the current focus on legislation is misguided. Or at least that’s my summary. Here’s some more summarized stuff from Prevor’s article. The first two suggestions caught my attention – the rest is boilerplate stuff. (

has an important role in food safety, but the current focus on legislation is misguided. Or at least that’s my summary. Here’s some more summarized stuff from Prevor’s article. The first two suggestions caught my attention – the rest is boilerplate stuff. ( third-party certification agencies. Trade buyers can establish their own standards or agree to accept other well-recognized standards, such as those of the British Retail Consortium. Adherence to these standards is then confirmed by various independent auditing groups. This is essentially the same mechanism the USDA uses to implement organic certification. The problem is that there is widespread corruption associated with these certifications, especially in areas such as China, Eastern Europe, and many developing countries, though auditors that are less than rigorous are also well known in the United States.

third-party certification agencies. Trade buyers can establish their own standards or agree to accept other well-recognized standards, such as those of the British Retail Consortium. Adherence to these standards is then confirmed by various independent auditing groups. This is essentially the same mechanism the USDA uses to implement organic certification. The problem is that there is widespread corruption associated with these certifications, especially in areas such as China, Eastern Europe, and many developing countries, though auditors that are less than rigorous are also well known in the United States. Canwest News Service reported

Canwest News Service reported