Irwin Pronk, principal advisor, HACCP By Design, has over 35 years of experience in the food processing, animal feed and packaging industries, has worked with over 400 companies and trained over 10,000 individuals.

In 2005, Irwin was recognized by the Ontario Food Protection Association as Sanitarian of the Year.

In 2005, Irwin was recognized by the Ontario Food Protection Association as Sanitarian of the Year.

Irwin writes, worried about your upcoming GFSI* audit? Scrambling? Stressing about possible non-conformances that may arise unexpectedly? Concerned about the potential reaction of senior managers? Customers?

The best approach is always to be prepared, principled, open and transparent. By identifying and addressing potential issues up front, and keeping your key players involved at every stage, you will not only help your audit go smoothly, you will have an increasingly solid foundation for achieving your long-term goals by developing broad-based awareness and participation. That is the cornerstone of a culture of safe food production.

In this series of 7 articles, you will learn how to:

- Ensure your Food Safety and Quality programs are effective and efficient.

- Be ready for all audits and be able to present your plant, managers, programs, and procedures in the best possible light.

- Continually improve yourself, your system, your staff, and your senior managers to be more preventive and proactive.

(Irwin wanted to do a 7-part series, but I edited it into one, especially since I’ve sat on the piece for so long).

The food safety programs themselves are intended to produce a calm confidence, though that is rarely the case. How do we keep them running at 100%, and even improving? As well, dealing with the re-certification audits is complicated requiring a great deal of thought and energy. The primary issue being consumers’ food safety but we can’t forget our customer’s requirement that certification is maintained, all the while we have a busy food processing plant to run.

What is the best way to prepare for your upcoming re-certification audit? We want to foster a food safety culture. An audit can also be a good way for us to get a second opinion on how the system is designed and how effective it is. For this to be more likely to occur, choose your Certification Body (auditing firm) carefully, not just based on price, so you can be more confident to get helpful insights from the auditor! Easy audits are a waste of time and money, accomplishing far too little.

The biggest pressure we feel at the time of the audit is the customer’s requirement to maintain certification. No one wants to be cut off or have people wonder about what’s going on at your company.

So how can you and your team walk into the audit in a positive frame of mind, clear on where the strengths and weaknesses are and having a plan in-place to deal with them. It is possible, and I’d like to go through a number of suggestions to help you!

I do want to say up front that the approach being suggested is ‘the high road’, a principled approach that is open and transparent. I have found it works best. Hiding things and covering up issues gets everyone nervous and if auditors get the impression that anyone is deceiving them, they will react and there is no predicting how they will handle it. When we are well prepared, open and transparent, it builds confidence and diffuses potentially explosive issues.

I do want to say up front that the approach being suggested is ‘the high road’, a principled approach that is open and transparent. I have found it works best. Hiding things and covering up issues gets everyone nervous and if auditors get the impression that anyone is deceiving them, they will react and there is no predicting how they will handle it. When we are well prepared, open and transparent, it builds confidence and diffuses potentially explosive issues.

Experience has found the following six factors to be most helpful.

- Be sure previous audit non-conformances are resolved and potential Major or Critical non-conformances are addressed.

- Audit the plant for the obvious GMP issues.

- Rigorous Internal Auditing.

- Communicate potential non-conformances. to Senior Management

- Manage the audit.

- Don’t do this by yourself! Get a second opinion.

The best approach is always to be prepared, principled, open and transparent. By identifying and addressing potential issues up front, and keeping your key players involved at every stage, you will not only help your audit go smoothly, you will have an increasingly solid foundation for achieving your long-term goals by developing broad-based awareness and participation. That is the cornerstone of a culture of safe food production.

- Be sure previous audit non-conformances are resolved and potential Major or Critical non-conformances are addressed.

You will likely have a long list of things to accomplish. Ensuring the non-conformances from the previous audit are closed, should be at the top. Minor non-conformances that are identified a second time automatically move up to a Major non-conformance level, and one of our goals will be no Majors.

What happens too often after an audit is we make promises about completing minor non-conformances, with the best of intentions, but life and work get in the way and we lose track. Don’t let that happen. Schedule follow-ups, in fact, consider scheduling internal audits of those non-conformances after 2 months and again after 6 months to ensure they are completed and working effectively. Having the larger Internal Audit team involved, and reporting monthly to Senior Management, keeps everyone accountable and on their toes, including us.

Some jobs are complicated, involve a lot of people (sometimes Corporate folks, IT or HR, not to mention the sometimes long and drawn out process of capital requests), are a lot of work and take a great deal of time. For example, fixing a Preventive Maintenance program that was designed and issued by Corporate will be difficult and slow. Even when things take much longer than expected we have to remember that a year later, we can’t be talking of progress, we must show completion. You may need to put in place a manual, paper-heavy process in the meantime, but the issue must be addressed and there must be proof.

During the last audit when the auditor found the non-conformance, it would have occupied quite a bit of their time and very likely prevented them from looking further into other aspects of the program. So rather than just addressing the non-conformance, look at all the other parts of the requirement, and your program, and be sure they are complete.

Maintenance is an example. The issue identified by the auditor may have been a worn, frayed belt, but the underlying problem may have been that the belt was not identified in the Preventive Maintenance system. Be careful to look more broadly. Are all the product contact surfaces included as Preventive Maintenance (PM) checks and are they highlighted as food safety priority PM’s. Examples are pump impellors, blenders, conveyors, depositors and fillers. Is the status of the PM program reviewed on a weekly basis? Have any incomplete PM’s that relate to Food Safety been highlighted, discussed and corrective action been determined and documented? Are records kept of these meetings?

Major & Critical Non-conformances

Major & Critical Non-conformances

While we must prevent non-conformances from recurring we must also ensure that there are no Major or Critical non-conformances. Examples of Major non-conformances could be;

- Ingredients in the receiving or production areas that are not approved through the Supplier Approval Process.

- A new processing line installed but the HACCP plan has not been updated to include it.

- A new allergen introduced with the controls at Product Development and the HACCP Team failing.

- Ongoing environmental Listeria positives in the processing or wash-up areas.

- Out of specification micro tests of finished product without any documented corrective action.

- Foreign materials findings / complaints not investigated thoroughly.

Critical non-conformances are even more significant as they can stop the audit and result in a failure. Examples of Critical non-conformances could be;

- Allergen cross-contamination,

- Mislabeling involving allergen-containing products,

- Condensation falling onto Ready To Eat (RTE) product,

- Gear oil dripping onto product

- Blender paddles heavily worn with loose burrs of metal.

In summary, your top priorities are “Major” and “Critical” non-conformances. Be especially careful to have previous non-conformances completely closed. This will be the auditor’s first task. Be sure the non-conformances are completely closed, not just improved and consider if there are weaknesses in any other areas of the program.

- Audit the plant for the obvious GMP issues

Don’t get caught with straightforward, easily prevented non-conformances. There will always be a handful of minor non-conformances, but if you want to consistently get a low number of Minors you must prevent this type of non-conformance from popping up (especially if you are shifting to an unannounced audit). This kind of non-conformance is where the entire plant management team rolls their eyes, as if to say “I can’t believe we missed that!”

Here are some examples:

A cabinet, in the production area, contains a can of non-food grade solvent, plus a squeeze bottle of ink jet cleaner that is not labeled.

Other examples to watch out for are packaging containers used for purposes other than food, such as a pen holder at a Supervisor’s work station, or maintenance parts stored in jar in the Shop.

Because floors can harbour dangerous bacteria like Listeria and Salmonella we need to be making repairs promptly and regularly. Scheduling the repairs takes time. If we begin early enough, it can be done at standard hourly rates, but waiting until the last minute results in us having to pay overtime rates. Cracks in the warehouse should be caulked, whether saw cuts or stress cracks.

The most sensitive areas are typically packaging and finished product handling, then the processing area, raw material preparation, then the warehouse.

Additional examples include;

- A column was getting damaged from bulk sacks being lifted up beside it. The bumping over time was causing paint to flake and even concrete to be chipped off. It was skinned with stainless steel, but even that took two attempts to get it right. The first version was knocked loose.

- Condensation dripping due to cold air from outside, for example, may a very expensive ventilation, humidity reduction or increased air flow. Condensation can become a critical non-conformance if in falling from the ventilation hood, cold water line or ceiling, the water drips onto cooked, Ready To Eat product.

Beware of auditors’ demands. One example recently was some wood ceilings where the auditor had found a couple of localized mold problems and stated that all the ceilings be ‘sealed’ or coated. The actual cause of the problem were two cooling units that were spattering droplets of water, wetting the ceiling. Why was water spattering? The drain pan was dirty and the drain was plugged. We had the pan and drain cleaned and the entire unit put on a cleaning schedule. The ceiling was then cleaned and the mold never returned. Many problems have simple solutions.

You will likely find temporary repairs. Tape around air lines, ‘pigs’ soaking up leaking oil, and more. They may be as simple as a piece of plastic used to divert a cool breeze or a piece of cardboard used to help product move around a corner.

There are times when a repair cannot occur until the line is down. A better options for handling situations like this include using a C-Clamp or vise-grip to hold a broken weld, but put a Maintenance tag on it. As well, open a Work Order.

On a production line of packaging film, picture a number of fast running bearings that leak oil very slowly, with no known solution. Many options had been tried though none had worked. In the meantime, the Operator had been given a daily checklist to inspect for oil, and wipe as necessary. Observing the piece of equipment the day I was visiting, it was found that oil was dripping. The checklist was found behind all the paperwork on the Operator’s desk, incomplete. Was the checklist missed in the daily review of records? Why? Was this process audited (or followed up)? This could have become a critical non-conformance if oil was found to be dripping onto the film.

Finding these types of problems takes time. It requires walking up and down each line and around the outskirts of each department. You need to be the one to find a burr on the edge of a blender scraper blade, cracked Lexan or the worn flashing. It could be as simple as a few dead flies or ants in a corner, or over-greased bearings that cause a minor non-conformance. Figure out where they came from and solve the problems. Rather than have the Quality department do all these inspections, have Operations identify a key Supervisor in each department to do the inspections, with the help of Quality, and the support of Maintenance. This gets the job done, but more importantly teaches the Operations team and keeps responsibility where it belongs.

- Rigorous Internal Auditing

Along with the program Corrective Action Preventive Action, Internal Auditing is one of the most important management tools you could possibly use to promote food safety. To make the most of it, use the best auditors you can find, and develop your team so that they will learn to audit even more rigorously than a 3rd party auditor. This is possible, because you know your plant best.

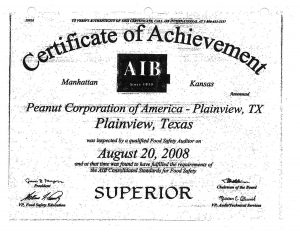

Your internal audit process should find far more non-conformances than any 3rd party auditor will. Let’s consider how many recalls we have had in our country from plants that had been recently audited. What does that say of programs and the third-party process? Weakness on both fronts! Don’t forget Peanut Corporation of America! Many of the plants having recalls lately have been GFSI certified. Don’t rely heavily on any kind of 3rd party audit, especially for a supplier who provides you an important ingredient. If you’ve got a lot at stake, get over there and check them yourself! The same principle holds true in your plant. No one knows your plant better than you do.

To do a great Internal Audit you need a great team of people.

One large production site has 3 of their site’s 4 Directors on the team, and the Internal Audit team of 23 persons audits their integrated program of ISO9001, ISO14000, OHSAS18000 and FSSC22000 at the same time. At another site the Internal Audit team includes a Purchasing Manager and Financial Controller. These are unique team members but their focus is typically on higher level programs, ‘systems’ audits, like Supplier Management, Corrective Action or Management Review. Because the Finance department, for example, is audited regularly themselves, their staff make good auditors. Also, more and more often, plants are asking a consultant to participate in their company’s internal audits, having them visit 3-4 times per year.

The key point here is that you need to know your own issues. My motto is “Surprises are great at birthdays and Christmas, but at work they stink.” So, even when good things happen, it shouldn’t be a surprise, it’s the result of concerted effort in a prescribed direction.

It is strongly recommended that Internal Audits happening more often than less, at least every month, and findings reported to senior management monthly, reporting non-conformances, corrective action and whether the Internal Audit team is on schedule or not.

Be sure the Internal Audit team has good tools to work with. Use a checklist and be sure the audit standard is available to them so they are thorough. Check the details. When interviewing, don’t take people’s word for it, ask for evidence. You need objective evidence of conformance or non-conformance and each department’s staff need to held accountable for the details of their program. Take the time necessary to be thorough. When they have had problems, check the communication and follow-up to make sure that the corrective action ‘loop’ is closed and everything is well documented.

When there are Minor, Major or Critical non-conformances, open a Corrective Action (CAR, NCR, CAPA etc.). This documents the issue and gets people’s attention! But, be sure everyone involved follows through so they are resolved and signed off (complete). No one wants to get a non-conformance for a corrective action program. Do your best to avoid that embarrassment.

A rigorous Internal Audit program can not only find problems but with practice and skill, find more subtle indicators of weakness and even identify negative trends so we catch them before they become a problem, building an environment where we anticipate and prevent.

- Communicate potential non-conformances. to Senior Management

As you approach a re-certification audit, be careful to be realistic and admit that there will be problems that won’t be completed in time for the audit. Don’t just hope they won’t be noticed or simply worry over what will be observed by the auditor. Create a list of the issues at your facility, and prioritize them. Which of these issues have the potential Critical, Major or Minor non-conformances? Some issues may have just recently arisen and others have been difficult to resolve over an extended period of time. Also, be sure senior management knows the risks. Do not leave them unaware, and don’t tell them at the last minute. With their understanding, you are more likely to have their support.

Once you have prioritized and communicated, think about how to deal with these areas of weakness during the audit. My advice is to consider  documenting them using a Corrective Action (e.g. CAR, CAPA, NCR etc.). There are a number of reasons why this approach is strongly suggested. Trying to hide the problem or waiting to see if the auditor sees it is nerve-wracking, plus the auditor’s reaction is much too hard to predict. My experience is that being honest and transparent does a lot of good. Not that you will tell the auditor all of your issues at the start of the audit, but if they do see the problem during the audit, you can be prepared to calmly respond by saying “Yes, we’ve observed that as well. We are working on it and here is what is happening.” Show the auditor the Corrective Action document that would include a description of the problem, root cause analysis and the corrective action plan. Years of experience has shown this brings calm to a difficult situation, it also builds the auditor’s confidence and trust in you. In more than one situation, a non-conformance that could potentially have become a Major, become a Minor. In other situations a Minor became an Opportunity for Improvement (OFI) or just a note in the audit report.

documenting them using a Corrective Action (e.g. CAR, CAPA, NCR etc.). There are a number of reasons why this approach is strongly suggested. Trying to hide the problem or waiting to see if the auditor sees it is nerve-wracking, plus the auditor’s reaction is much too hard to predict. My experience is that being honest and transparent does a lot of good. Not that you will tell the auditor all of your issues at the start of the audit, but if they do see the problem during the audit, you can be prepared to calmly respond by saying “Yes, we’ve observed that as well. We are working on it and here is what is happening.” Show the auditor the Corrective Action document that would include a description of the problem, root cause analysis and the corrective action plan. Years of experience has shown this brings calm to a difficult situation, it also builds the auditor’s confidence and trust in you. In more than one situation, a non-conformance that could potentially have become a Major, become a Minor. In other situations a Minor became an Opportunity for Improvement (OFI) or just a note in the audit report.

Here are a few specific examples:

- Positive Listeria or Salmonella results in a Cooler or Wash-up Room: Be ready to show the history of the problem and the current corrective action activities including capital requests and work orders.

- Recurring sanitation problems such as high ATP results or microbiological swabs: Be sure you can show communication from the Lab (QA) to Sanitation and Operations, and well documented corrective actions reported back to QA and management.

- Preventive Maintenance behind schedule, or perhaps the Internal Audit program or the Master Cleaning Schedule: Open a Corrective Action to document the current status, clearly state the priorities (e.g. food contact equipment PM’s) and how we are in the process of getting back on track.

- Perhaps not all suppliers are approved or some files are incomplete: Be very clear on the actual status. For example, only 70% of suppliers are approved. Be ready to show Emails following up with the other 30% of suppliers, planned visits, the status of the higher risk ingredients and clarifying that they are the first priority. In preparing for the presentation to the auditor, my suggestion is to have, for example, four files to show. Choose three which are complete and the fourth partially complete. Rather than wait for the auditor to choose suppliers randomly, prepare an honest representation of your situation ahead of time because you already know what questions they will ask. You have the standard.

- An ingredient or two has been out of specification but the plant was able to use it: Be sure to document the issue in something like a Specification Deviation. The extension of an ingredient’s shelf life could also be documented this way. Other examples of this include finished product quality (e.g. viscosity).

- A metal detector producing more kick-outs than normal (perhaps even linked to consumer complaints). Document the incident in a Corrective Action Preventive Action document, investigate the root causes carefully. Investigation and corrective action must be very convincing and may include machine overhauls or even the rental of an X-Ray unit.

Senior Managers do not like surprises. If Senior Managers are being apprised of issues on a monthly basis then they should have all the information they need. If this is not your normal approach yet, at least provide them with a list of what you see as potential issues and do this as soon as possible. This should be at least three months prior to the audit.

- Manage the audit

The auditor leads the audit process, yet, you can manage a great deal of it if you plan carefully. This is not about being sneaky or devious, but intentional, planning your presentations and talking points so things don’t get missed and each department knows what their role is, able to articulate their programs and procedures, and shouldering their responsibility. It is important to have every department involved and this is a way to encourage it. One underlying goal is for each department to weave food safety and quality into their programs and procedures, not QA to run it. This planning process encourages this. What follows are some examples

Plan the agenda.

Prior to one recent audit, a month before the audit, no agenda had been sent by the Certification Body. The plant requested it. When the agenda arrived a few days later, it was obvious that many changes were needed. Because of the size of the plant and the way responsibilities were shared between departments too much time would be wasted. For the auditor’s sake it was rewritten, organized by department rather than audit standard sections. Each department was consulted to be sure it suited their schedules. Waiting until the day of the audit to correct it would have been confusing. Remember that even though the auditor may have been there a year before they likely only have a vague memory of the plant, people and situation.

Plan each department’s ‘presentation’

Everyone gets very nervous during audits and don’t always represent themselves and their programs very well.

As well, auditors also can use terminology that unfamiliar to people. Because of the confusion, too often, managers assume they don’t do what has been asked for, or don’t have that program. Very often they just call it something different. Meeting with each department, reviewing their sections of the standard will allow you to help them plan their presentation. Most plants try to avoid this problem by having QA answer as many questions as possible since they know the standard best and understand the auditor’s terminology. This causes a long term problem that negatively affects the food safety culture of the plant. With this approach other department managers are not likely become familiar with the programs expectations and thereby fail to shoulder their responsibilities.

As well, planning will help each person present their case honestly, and in the best possible light. Similar to an example in the last article, if there are 62 supplier files but only 25 complete ones. Do not just present your best ones and hope the auditor does not ask for more. If they do, and review a file that is incomplete they will not trust anyone in the plant. Consider showing two complete ones and 3 that are in process. All programs are in some state of improvement.

In the example below is an excerpt from a Recertification Audit Plan, an introductory paragraph and one example from the Human Resource department, one of ten department-specific plans for the site.

General notes for all departments:

- If there are any disagreements with the Auditor, do not argue. Ask to see the requirement in the standard.

- Don’t accept non-conformances too easily. Bring all the relevant information you can think of to the Auditor to help them make the right decision.

- Rather than pulling original documents to show the auditor, consider making photocopies, preparing the examples in a series of folders, then after the audit, the paper can be recycled, and no re-filing needs to be done.

Human Resources – Training

- Start by showing the training procedure (be sure to highlight how the site verifies the effectiveness of training).

- Show how the Training Matrix works.

- Have some examples of ‘competence’ or qualifications ready. The obvious ones are likely the Quality Manager and Lab Technician.

- Production training. Have the training files ready for about 5 people across the various departments and including a Temporary employee, a Contract person as well as Full Time staff members.

- Be sure the evidence shows that the effectiveness of the training has been checked.

- Annual Training

- Show what subjects were covered.

- Show how attendance was taken, and how those that missed the main sessions were later trained.

- Give a couple of examples of the two people who have been noticed working in production, having excellent qualifications we were not aware of, and were subsequently transferred to the office (more responsible positions). Perhaps introduce them as you walk through the office. Also mention examples of potential problems that were noticed by staff, communicated to their Supervisors and prevented.

Other departments that need similar coaching are;

- Purchasing

- Lab

- Maintenance & Utilities

- Senior Management

- Operations

- Warehouse

- Security

- Quality Assurance

Preparing examples of training records, for example, keeps you in the drivers seat. Waiting for requests for records from auditors, then scrambling to find the information quickly can easily result in forgetting something important. As mentioned before, we know the standard so we also know what questions the auditor will ask. If you have 30 minutes with the auditor, have a presentation ready to more than fill that time slot. Not with filler but will a clear review of the programs and procedures.

This may sound like a time-consuming process but so is responding to non-conformances, and this feels much better.

A brief word about disagreements with auditors. First of all don’t get mad. Most people loose their powers of reasoning when they are angry. Be careful there are no disparaging remarks when difficulties are encountered. If someone is loosing their temper they should leave the room.

If the auditor seems to be off-base, and you don’t understand why they find an issue so important, or they don’t seem to be understanding your explanations ask them to explain further. Thankfully this is a rare situation. Ask where that requirement is in the standard and the guidance documents. Minor non-conformances do get assigned that should just be OFI’s and Major non-conformances that should only be Minors, but in order to wisely appeal a decision we need to know the standard thoroughly.

Judgments can always be appealed through the Certification Body if we are sure the auditor is off base. The important thing is that we are ‘right’.

Have the auditor interview each department in their own area.

Auditors are typically placed in the main boardroom (as far away from the plant as possible and near the coffee pot) or in a QA meeting room. First of all, we want to dispel the notion that the food safety program is run by QA. Our intent should be to have each department integrate the food safety and quality elements into their programs and procedures. Make every effort to accomplish this. It is best for the overall food safety of the product and consumers. The culture of food safety has to permeate every corner of the plant and this is one way to encourage that.

Include supervisors and staff as the auditor is touring the building, a different supervisor in each area. There should not be too large a group, but include nearby people and introduce them. They can then overhear the questions and answers, thereby learning and becoming more comfortable with the process. They will see the same things as the auditor and if there is an issue, will better understand why.

The auditor does need a home-base. Make is comfortable. Have lots of good snacks, especially your own products if possible.

Another point to consider is conducting what could be called a ‘first impressions audit’. While it sounds odd, pretend you are the auditor first driving up to the plant and arriving in the lobby. Drive to the plant from both directions so see how it looks from the road. What needs to be cleaned up? Park in the visitor’s spot. Are there weeds? Walk to the front reception area. A snow shovel or broom in the reception area all reflect poorly on the organization. Excellent housekeeping, even in the meeting room, communicates attention to detail. Walk from the office to the plant, and decide which route is best to take.

There are many objectives that need to be achieved. What effort will you make to improve the culture of food safety, engage management and get closer to achieving zero non-conformances? The details are important!

Don’t do this by yourself! Get a second opinion

Yes, you know your plant best, but a calm, second opinion from someone who has done this countless times can help with a broader perspective and even positively influence your senior managers when things need to get done. The second opinion can help you sharpen your priority list especially because the list can be very long and you could use some help to separate the A priorities from the B’s and C’s. Be sure the person you bring in knows your industry well but also understands the broader food processing industry and even other standards for a more complete perspective. As an aside, although a plant is certified to one standard it is beneficial to be knowledgeable of the other standards. Each has its own unique perspective and requirements. Incorporating them will benefit your food safety program. Keep copies of the most commonly used standards such as BRC, FSSC22000 and SQF.

Yes, the big audit is coming but don’t loose sight of the fact that the point of the program, and being certified, is protecting the consumer. An audit is supposed to be constructive feedback and we want to make the most of that. Hope for some great insights from the auditor! Easy audits are a waste of time and money.

It is possible for you and your team to walk into the audit in a positive frame of mind, clear on where the strengths and weaknesses are and having a plan in-hand in dealing with them. You can do it, and hopefully the suggestions in this series of articles are helpful.

It bears repeating, in dealing with the audit and the auditor, take ‘the high road’. Take a principled approach that is open and transparent. It works best. Hiding things and covering up issues makes everyone nervous and if auditors get the impression that they are being deceived, they will be very upset and there is no predicting how they will handle it. When we are well prepared, open and transparent, it builds confidence and diffuses potentially explosive issues.

How do you spell stress? GFSI? Here is the list of 6 areas that in my experience have been most helpful in reducing that stress.

- Be sure previous audit non-conformances are resolved.

- Audit the plant for the obvious GMP issues.

- Rigorous Internal Auditing.

- Communicate potential non-conformances.

- Manage the audit.

- Get a second opinion.

Your certification and re-certification audits can be a constructive and positive event, encouraging the production of high quality, safe food.

In general, these documents should give clear answers, and auditors should be ready to understand and analyse these information. The aim of this chapter is to give reliable advices for interested food auditors with concern to the examination of technical data sheets for all possible ingredients in the food and beverage sector.

In general, these documents should give clear answers, and auditors should be ready to understand and analyse these information. The aim of this chapter is to give reliable advices for interested food auditors with concern to the examination of technical data sheets for all possible ingredients in the food and beverage sector.